The American Dream was once a horizon, not a gated path. It carried a collective promise. But living in places like California today means being exposed to beauty and the possibility of exclusion.

For a nation, looking at its past is like looking in a mirror: the image may be disfigured, flattering or harsh, but without it, societies can hardly recognize who they are. As a Spaniard living in the US with my wife (American) and children (dual nationality), I’ve been thinking about this.

If I were to analyze the society from the place where I live and the access my family has had since moving here in mid-2022, I have little to complain about. But I can’t help but remember a video I watched recently of James Baldwin addressing the students at Cambridge University’s Union Hall during a debate against William Buckley Jr. on the topic of the American Dream no less: his point was that, if you bar a portion people from accessing the American Dream, their exclusion doesn’t just harm them, but it weakens the very foundation of that dream for everybody.

Here’s how Baldwin closed his participation in that debate:

“It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one-ninth of its population is beneath them. And until that moment, until the moment comes when we, the Americans, we, the American people, are able to accept the fact that I have to accept, for example, that my ancestors are both white and Black. That on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity for which we need each other, and that I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity. I am one of the people who built the country–until this moment, there is scarcely any hope for the American dream, because the people who are denied participation in it, by their very presence, will wreck it. And if that happens, it is a very grave moment for the West. Thank you.”

Be happy—and don’t look too close at your neighbor’s expulsion

I wonder if these words could now be extended to the subclass of people who are now living in fear because they can’t attain full citizenship. Many live in places not far from me, where people who’ve lived here longer than I have, contributing much more to this country and being more loyal than anyone to the promise of the American Dream, are often being taken advantage of, not the other way around.

Anybody with a conscience should think about it, but many are choosing silence or indifference. To Baldwin’s point, thinking about decades-long neighbors in pure administrative terms after benefiting from their participation in society is a recipe for the overall impoverishment of a society as a whole. Personally, all is well, thanks for asking. However, thinking about others nearby struggling makes me uneasy. My paperwork was processed in around seven months total, from the first form submitted to my Green Card being mailed. Others wait for years for a rejection.

So yes, we’ve been able to live in the San Francisco Bay Area, in a more than convenient school district for our kids, and our oldest daughter was recently accepted to Cal. Not only that, but we benefit from the fact that Kirsten grew up in the area, and she has relatives and friends around that make our life even more agreeable. Add to this the ridiculously nice weather of coastal California, and the fact that I can explore well-kept trails all over tree-covered hills overlooking the bay, UC Berkeley, the Golden Gate, and San Francisco.

It’s not realistic to have a nitpicking attitude when you’re aware of what’s in front of you. Many people put a good deal of energy into making the rest of the country believe that this bay is going to hell in an unfathomable spiral of doom: either I manage not to see that Dantesque reality because I’m very protected and aloof, or some people are exaggerating the many dysfunctions I too see. Even taking these into account, life is good here. That is: for those who can afford it.

Go West, and perhaps bounce back

Not all the press is bad: Niche named the place where we live the healthiest to live in America, out of 229 locations ranked, and I presume the main factors for this success aren’t overall wealth, nor access to goods and services that determine overall quality of life, because some places nearby with similar access rank very poorly by comparison.

Considering health indicators, access to doctors, mental health resources, and proximity to fitness facilities and the outdoors, this seems to be the place (and for the third consecutive year). Not bad for an alleged hellscape. Now, imagine if it were also more affordable.

“Go west, young man” captures the imagination of generations of adventurous spirits, but does it hold its original meaning in our times? The manifest destiny, the motto for opportunity in the mid-nineteenth century—from Midwest farms to the prospect of gold in California—is alive and well for a few, but the rest face an entry paywall too difficult to afford.

California, Oregon, and Washington State still draw people with their climate, technological opportunity, culture, and a lifestyle built around access to the Big Outdoors. However, the drawbacks are becoming insurmountable to many: high housing costs, higher insurance premiums (or no insurance) due to fire risk, and air quality during fire season are shifting the West Coast dream to some and turning it into a series of imperfect though more affordable New Wests.

Idaho, more than great potatoes

The frontier ethos survives, though it’s becoming decentralized—and not much more affordable, at least not for longer: those leaving expensive cities to settle in Texas, Arizona, Colorado, and Idaho, are having a harder time finding an affordable, positive transformation of their lifestyles, so they are trying to invest New Wests (in plural).

As remote work hubs that set out as alternatives to San Francisco (like Miami and Austin) are unafordable themselves, places where backyards confound with the outdoors like the suburbs of Boise, Salt Lake City, and gentle towns across the most unexpensive Rockies are attracting young families in search for a new beginning “out West,” even when they come from West of that new-ish West.

So “Go West, young man,” the phrase attributed to Horace Greeley, an editor for the New-York Daily Tribune who wrote it in July 13, 1865, should now include a warning like those that advertising voices say at the end of a commercial at such a hefty speed that we think we’re listening to a caffeinated TikTok pundit: “Conditions apply.” Here’s the original context:

“Washington [DC] is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting, and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

Interesting point, and a prescient one for that matter, Mr. Greeley, one might say, which makes today’s complaints not that original. Now, change 1865’s DC for every expensive coastal metro area today, add to the mix baseless conjectures regarding insecurity, and you will get the idea of where the wind is blowing.

An old dream that refuses to go for good

With all its flaws, it’s remarkable how this old refrain, an evergreen in American pop culture turned into a punchline exported as soft power through literature and cinema, survived every convulsion in the new country and helped build it—just the way Greeley suggested.

To many, it now rings hollow, as the ideal of “boundless opportunity” has narrowed, evolving into a gated path—the luring attraction of finding one’s own destiny on the Pacific shore has begun to reverse, as expressed in recent works like Conor Dougherty’s 2021 book Golden Gates: The Housing Crisis and a Reckoning for the American Dream, and Malcolm Harriss’s 2024 Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.

But was it ever easy to make it West of the Rockies? Since the times of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to find the mythical Northwest Passage (a dream only surpassed by the idea of the Eldorado brought from the Old World by the Iberian conquistadores), or early migrations like the Oregon Trail, the West has built a character and a reputation of roughness that has always demanded a sort of merciless resourcefulness. And there’s an allergy to complain, self-pity, and top-down mentality that, for better or worse, survives to this day.

Horace Greeley encompassed all the shortcomings of his age, but also was a champion promoter of reform and ingenuity. As a progressive reformer, he combined entrepreneurial zeal with social conscience, supporting labor rights and women’s suffrage and public education, and opposed slavery. Hence, his vision of expansion was tied to opportunity and social mobility.

His rationale is a lesson for today: instead of leaving the destitute and least adapted behind, he fought the zealots of good-old European-style gatekeeping (limitation by wealth, elite education, and family connections), encouraging the new country to find a different way to “lift the tide” to everyone. Because when things go better at the bottom, cohesion grows within society as a whole. He wasn’t wrong, and decades after his passing, a president who came from old wealth and privilege, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, sought Greeley’s advice and helped everyone, not only those already “in.”

The small print is getting bigger

As for the immigration barriers, in Greeley’s time, the country was expansionist and inclusionary (so long as you were European, the less swarthy and the more Protestant the better). By contrast, today’s policy narrows the dream to a select elite needed in essential labor sectors, outright excluding the rest—it’s not that Americans prefer an “orderly immigration”; the sentiment seems to be more “no immigration at all, period.” Quite a change in the sentiment of a population almost completely composed of previous waves of immigrants. In a twist of history, the same way the biggest zealots of the Catholic faith were born in converso families during the Spanish Inquisition era, sometimes the latest immigrants legally naturalized are the most fervent gatekeepers in today’s America. There’s a lesson in human psychology in this.

As a newcomer to California, I’ve often observed that the ideals of the American Dream are only held among immigrants, now officially barred from attaining it. The US West Coast is a place that I’ve visited for long periods for the last 20 years, though I only started living here in late 2022; from my observation, for the first time since early in the century, the very ideas that connected places west of the Rockies with boundless opportunities and a right to seek one’s own path, are in geopardy for everyone for different reasons in every cohort:

Paradoxically, those still lured by this illusion—the poor farmer, the desperate migrant, the destitute in search of a bearable weather all year round—have never been less welcome in recent history, whereas the fortunate—capable of mobilizing resources, hyper-educated and already mobile—have turned complaining about the dysfunctions of the West Coast into a lazy punchline.

My take on this debate: the “Go west, young man” is alive and well, but it’s a VIP access that only tries to lure those already in a good position (either owning property, or financially independent, or fluent in today’s AI tech currency, or everything at once), leaving the rest out. It’s a big “Go west, young man, IF you comply,” followed by a middle finger to everyone else.

The open road is gone for the many, paved in gold for the few

Or, this is at least the conclusion driven by a conventional vision of opportunity and fulfillment: a well-paid job, a house one owns, a family, many cars, disposable income to take at least one inspiring vacation per year, etc. But unbound prosperity for everyone and a robust, ever-expansing middle class aren’t self-replicating and self-healing entities that societies don’t need to foster and propel with decades-long policies.

The left-overs of American soft-power, and perhaps a personal predisposition to be attracted to the idea of a boundless country as expressed by literature and movies I’ve liked since I was a teenager, made me understand early on that myths are just an inspiration that everyone can adapt to their hopes and circumstances, and to me the dream was never outsized material fortune as a means to an end.

Call me an idealist, but what really caught my attention and attracted me (more as an idea than a realistic dream I wanted to pursue) was the boundless paths and roads, the can-do attitude, the raw beauty of the landscape: as a teenager, I got sold the idea as a teenager by gold seekers, loggers, beatniks, not Stanford or the then-incipient Silicon Valley.

Interestingly, circumstances brought me to write about tech in magazines during my early twenties, and not much later, I met Kirsten, a Californian from the San Francisco Bay Area, among all places on earth, so the dream landed on me before I actively sought “the dream.” And, if we lived for years in Europe while our children were younger, it was in part because there are other places on earth that can offer their very own version of fulfillment, many times on less materialistic and tolling terms.

It was also less complicated to us to seek our lifestyle, life on our own terms (working on our projects, raising three toddlers, paying an apartment and having all the basics covered) in Europe; in local terms, no Barcelonian will tell you that life is affordable, easy, or relaxed (let alone “pleasant”) in the city, because it’s one of the most expensive places to live in the Iberian Peninsula. However, compared to Paris (a city where we moved not long after), Manhattan (the place Kirsten was living when we married), or San Francisco, living with young children in Barcelona is easy-peasy, and much more affordable in relative terms if one wants their kids to attend good schools, do sports, etc.

Yet, with all the faws brought by the hyper-prosperity that has transformed the Bay Area and—thanks to a mismach between tech salaries and housing availability—the many things that make the place more expensive for everyone else, many of the things I came to appreciate in California and the US West in general are alive and well in a region with unveliable beauty and ridiculously pleasant weather all year round.

O pioneers?

Yes, housing prices, the fire threat, the gamble of sitting on the San Andreas fault, and the realization that many of the people across the United States who experienced a generational decline of opportunities and living standards will buy the hyperbole that media pundits are selling.

No matter what they say, California isn’t falling apart, and it’s one of the best places in the world to live by any possible measure, especially if you think that some of the challenges facing the world today can be solved with a great deal of ingenuity and a very particular blend of public-private education and investment. Only it has become too expensive and exclusionary for too many people.

It’s been a long time since the idea of a westward expansion in a boundless, young country was “the” dream on and in itself; like in Eastern philosophy precepts, the journey was the destination, and being brave enough to play a high-stakes life (trying to farm in rough territory, trying to hit a fortune in the middle of nowhere like the character of There Will be Blood, aiming at material riches seeking gold and finding them writing instead like Jack London…) was enough. Having the idealistic drive, the courage to even try a new life in the Frontier was already a “successful” existence.

Walt Whitman’s Pioneers! O Pioneers! is a picture of the collective unconscious in 1865, when the Frontier was wide open and all Americans were called (as “children”) to seize it.

Come my tan-faced children,

Follow well in order, get your weapons ready;

Have you your pistols? have you your sharp-edged axes?

Pioneers! O pioneers!All the past we leave behind;

We debouch upon a newer, mightier world, varied world;

Fresh and strong the world we seize, world of labor and the march,

Pioneers! O pioneers!

Does hyper-competition ruin great places?

This contrasts with the collective perception 160 years later. In 2025, the public perception of the call west got narrowed and cynical: it doesn’t demand tan-faced children with axes and grit (read: everyone with grit, not an insider elite), but résumés, LLMs and AI skills, good-to-great credit scores, family trust funds, and connections. Only the hyper-educated and those already in advantageous positions are welcomed to the modern Frontier of the West, not only along the coast from San Diego to Seattle, but also across the gentle college and mountain towns across the high desert, the Great Basin, and the western Rockies. It’s just getting more expensive, and it’s in part because many people along the coast figured that, by selling their property there, they can have a comfortable life anywhere else and will pay what it takes to get a place in Bend, Missoula, Bozeman, Boise, Spokane, you name it.

I thought about all this recently while we were traveling by car from Northern California to the Oregon interior, Eastern Washington, and along the Idaho tributaries of the Columbia River, following the route through Columbia River tributaries opened by to Lewis and Clark in their quest for an easy way West, as it’s noted all over the Nez Perce Reservation area.

As we cruised the road listening to music, talking, or too tired for either, we especulated about a future move out of the high prices and a feeling of hyper-competition that one might get near big coastal cities, especially when your children’s school calendar dictates which dates you can travel, tying you up with a big portion of the population living near you, which means you’d better have unconventional tastes and schedules if you don’t want to pay more for less, sit in traffic, elbowing ahead in ski lines, and testing your stoicism for a subpar experience of any activity outdoors.

It all made me think about alternative, affordable, viable ways of looking into the American Dream. Say you free yourself from school district dictates and organized sports for children by dedicating the time you’ll save while driving less and not sitting in traffic to help with homeschooling and helping your kids’ teams by coaching, assisting, organizing, etc. Then look for a property somewhere in the Rockies’ western slope to your liking, near outdoorsy college towns—likely more expensive and already filled with L.A. and San Francisco expatriates—or in the middle of nowhere (prioritizing size, or the presence of a creek, a pond or lake, or perhaps a like-minded local community).

Wallowa mountains: little-known oasis in the West

During our trip, we visited friends and acquaintances who have followed their own call outside the country’s most expensive areas, which for them eased the way to live life in their own terms, being present in the activities they choose to do, and very often doing so while staying connected to people around them and to nature (two of the reasons they moved there to begin with).

We’ve heard very often that stress and tenuous schedules near urban areas make people less connected with each other, and so a paradox emerges: density doesn’t necessarily bring more opportunities for true connection with others, and oftentimes it can beget alienation. By contrast, moving somewhere more rural by choice also goes hand in hand with personal agency in one’s own day-to-day schedule and economic independence due to significantly lower housing costs, telework, and early retirement thanks to passive income strategies.

It’s no coincidence that none of the people we visited had children living at home—either their kids were grown-ups, or they had chosen not to have any. Parents often choose to live near cities when they have children at home because dynamic urban and suburban areas provide a unique blend of practical resources, opportunities, and built-in support that is impossible to find in more remote areas—unless you build your own community with like-minded people.

On this trip, we had the pleasure of going through Joseph, a hidden jewel of a mountain town in Oregon’s little-known but mesmerizing Wallowa Mountains. Dan Price, whom we had visited ten years ago and has lived for 35 years in a “hobbit hole” by a river meadow he tends to, invited us to come by, so we visited him and got inspired once again.

When we first filmed him a decade ago, he showed us his 80-square-foot home and office where he once drew and printed Moonlight Chronicles, his hand-illustrated zine. Now 68, Dan still lives simply, happily, and with no regrets, and the saplings he planted around his friends’ property are now towering trees.

A day with Dan Price’s radical simplicity, 10 years later

He rents the meadow for just $100 a year, tending the land and keeping it fire-safe. His underground home stays a steady 50°F year-round—even through snowy winters—so his electric bill averages just $40 a month. Over the years, he’s added small comforts—like a salvaged brick patio and an earth-cooled outdoor fridge—but the heart of his life hasn’t changed: walking, drawing, surfing, and finding joy in “enough.”

Unlike Thoreau’s two years at Walden Pond, Dan’s experiment has become a life, and he told us with conviction that life is getting better everyday, now that he left behind a more intense period of his life and has managed to “live in the moment” by appreciating what he has at hand and the adventures he pursues upriver, a wild area rich in flora and fauna he calls his backyard. Dan doesn’t own the land he lives in, nor does he live in a conventional house, but these facts have not prevented him from successfully pursuing his surfer-artist seasonal existence and achieving both self-expression and self-realization.

For some reason, talking about our second visit to Dan’s place reminded me of the title of Yvon Chouinard’s pragmatic-idealistic autobiography, Let My People Go Surfing. Like Dan, Yvon was blessed with a connection to the Big Outdoors, which it the US West are of overwhelming beauty, from Yosemite’s El Capitan to driving along the Coast nonchalantly, to the majesty of the Cascades, the raw western-movie-worthy scenery of the Oregon high desert, the sheer size of the Columbia river, the army of fog as it advances in the horizon while one sits by the beach surrounded by driftwood and waves whose beauty won’t be ever captured by a human device, image or word…

Real prosperity and opportunity at the bottom

The coastal residents that the American heartland are trying to incentivize and make them move to places like Tulsa (Oklahoma), the Remote Shoals and the Remote Shoals (Alabama), Ascend (West Virginia), Northwest Arkansas, or Topeka (Kansas) aren’t the homeless and destitute in real need that have nowhere to go.

That’s exactly the paradox in the mid-twenties of our century, roaring for individuals and families with property and stocks, not-so-roaring for the rest, especially the young and uneducated.

Instead, the hollowed-out places in the Flyover states want to rebrand themselves as places of opportunity, attracting talent and combating the stigma of poverty and emigration to the Southwest and the coasts.

These programs are not “come one, come all” policies similar to the New Deal policies from FDR’s administration (1933-1939) as a response to the generalized destitution caused by the Great Depression; quite the contrary, they are carefully targeted at a narrow slice of people who already have jobs and proof of disposable income.

Like the Southern European countries trying to allure high-income expatriates with lifestyle and quality of life standards to boost local investment, Southern and Midwest US states have engineered with fancy presentations and sleek websites their very own myth of arrival, a “move here and thrive” for digital and professional homesteaders “tired of New York or San Francisco” but not willing to move to traditional Sunbelt destinations and Florida.

Roosevelt didn’t like the shantytowns mockingly named Hoovervilles (after Herbert Hoover), but as symbols of the Great Depression’s despair, they became his obsession; unlike today’s political class, FDR’s administration considered (realistically) that closing them without providing structural solutions to the destitute occupying them would simple move these informal towns from place to place, so Roosevelt fought them with targeted relief and housing.

Instead of pinpointing their occupiers with a mythical tale of virtue and hard work (and hence equating destitution with laziness and diluted lives), the New Deal prevented radical alternatives and the rise of American-bred extremism with work and relocation programs aimed at a collective uplift: “a rising tide for all.”

An old melody that fell out of fashion

With all the revisionist critique since the eighties, the New Deal accomplished something remarkable (arguably, with the help of World War II, which propelled the American heartland industry and provided a collective mission that everybody agreed on after Pearl Harbor), promoting prosperity by inclusion at the bottom instead of targeted inclusion that trickles down to exclusion at the bottom to boost GDP.

Relocation programs today arrive as local perks targeting those who already have steady jobs and can afford the mobility epitomized by the gentleman homesteader, some sort of neo-Jeffersonian curated migration for “the right kind of newcomers.”

At its core, the American Dream was never meant to be a gated path, but a shared horizon. From Baldwin’s warning in Cambridge to Greeley’s call to “Go West,” the promise has always carried a condition: it only endures if it’s open to all. Today, as myths of boundless opportunity meet the hard realities of exclusion, perhaps the real Frontier isn’t geographical anymore, but moral—our capacity to extend belonging and possibility to those still on the outside looking in. If we fail at that, no amount of good weather, good schools, or good trails will keep the dream alive. If we succeed, the road West may still lead somewhere worth going.

And yet, as someone who is both inside and outside, I can’t help but feel the contradictions more sharply. On one hand, my family enjoys the extraordinary advantages of life here—schools, trails, community, climate—things that make California feel like a dream fulfilled.

On the other hand, I’m aware of how provisional that belonging can feel, and how many around me, with deeper roots, are denied the same stability. To live here as a newcomer is to walk a ridge line: part of the view, but never entirely settled for good.

Perhaps that’s the most actual California condition—caught between promise and exclusion, beauty and fragility, dream and disillusion. To keep the dream alive, Americans will need to understand that there’s no possible paradise built on the shoulders of other people’s misery.

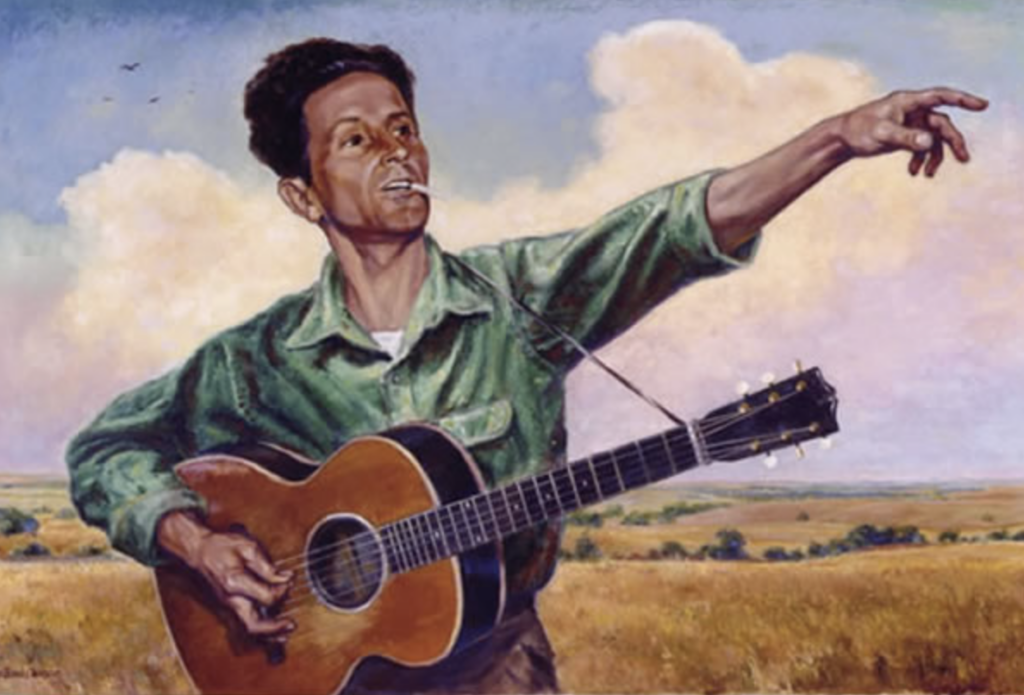

A metaphor for the country’s enduring allure, but also its contradictions, longing, and melancholy, this article is an attempt to turn Woody Guthrie’s This Land is Your Land into an essay (if only to counter Childish Gambino’s This is America vibes).

I rediscovered the song while watching A Complete Unknown, and, like in the movie, sometimes it’s best to go to the source to close the circle so the potential for infinite new beginnings remains alive.