After soil is contaminated, regeneration begins below the surface — where microbes, roots, fungi, and people work together to heal what the cleanup missed.

A recent technical glitch on our YouTube channel reminded us how fragile systems can be — one corrupted file, and the whole image turns dark. Thankfully, we got some help from our partner manager at the platform.

California’s landscapes face a similar transformative challenge, though on a scale that no patch or upload can fix.

Our newly assigned partner manager at YouTube jokes about being part of Generation Z — but she’s alright, LOL. She’s also genuinely familiar with our work, which makes the connection more fruitful and human. She lives near West Hollywood and walks to the local YouTube office. Talking with her, we asked about the recent fires in Altadena and Pacific Palisades and how they disrupted her everyday life. Like many Angelenos, she felt the impact indirectly, working from home until the smoke and chaos subsided.

Things aren’t back to normal for many people, and it will take time for that part of Greater Los Angeles to face the future with confidence again. As with any black-swan event, upheaval for some becomes opportunity for others — and not everyone is comfortable with outsiders arriving after the disaster.

No two charred soils are equal

Fires and industrial disasters strip ecosystems to their essentials—exposing the framework that supports renewal. Charred soil may seem ruined, yet it allows new life to emerge, and in places like California, many species have adapted to it.

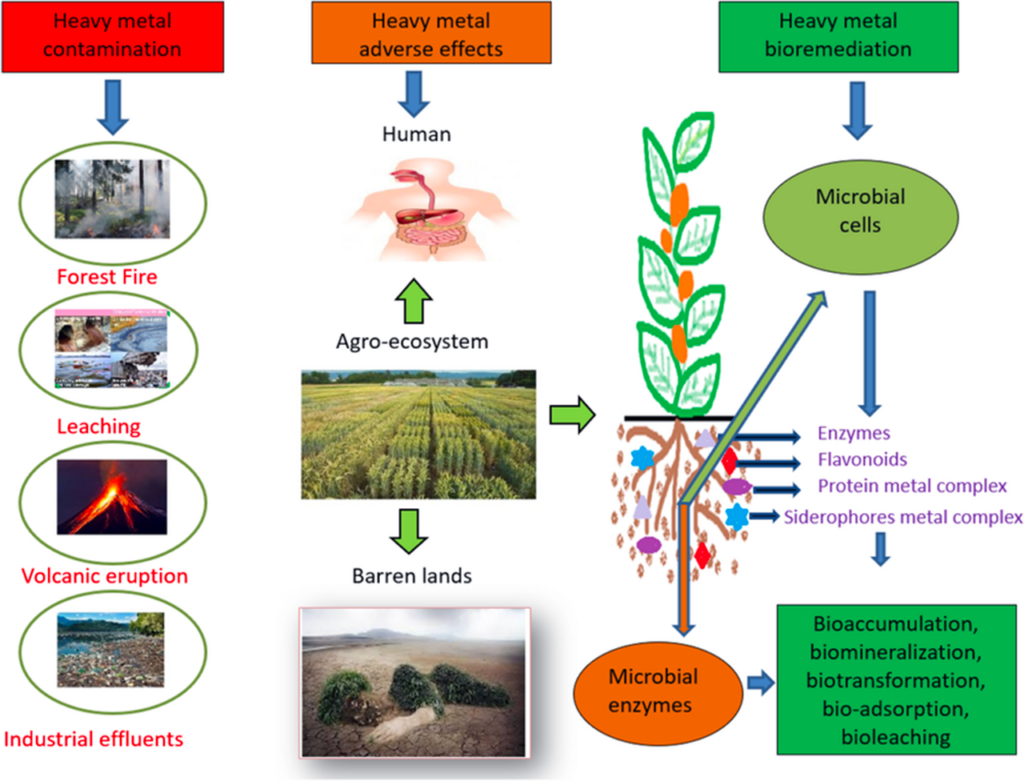

However, when fire reaches buildings and infrastructure, the composition of what burns is very different from that of forest fire ash. Instead of containing mainly calcium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus, which are nutrients plants can reuse, aiding soil regeneration, acting as mild fertilizer, they also contain heavy metals (lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury), asbestos, PCBs, dioxins, PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), and other persistent organic pollutants.

Structure fire can have very different toxicity profiles, and vegetation and soil composition may help mitigate its causticity (or high pH). Fortunately, many pollutants can be removed from the surface, and vegetation will accelerate recovery in places like California, as long as debris and surface ash are removed before copious rains push contaminants deep into the soil and natural aquifers.

Returning to Paradise

Across California and the US West, there are many encouraging stories that demonstrate urban and soil regeneration following a major fire. Few thought the Northern California town of Paradise was going to survive the November 8, 2018 Camp Fire, which wiped out the town, killing 85 people.

About 90-95% of Paradise’s structures were damaged or destroyed, which brought the population of 26,000 people before the fire to 4,764 in 2020. However, things are looking very different now: Paradise is booming, and by early 2025, the population had surpassed 11,000 residents.

Recovery in Paradise continues at a rapid pace, writes the local journalist Jake Hutchinson, blasting through projections from local and state government officials and even residents. There are 350 open businesses. Infrastructure is also back, with cable and water upgrades 73% completed. Wayne Kurtz, co-owner of the local Grocery Outlet, explains that the town now maintains two supermarkets on either end, with sales considerably higher than projected:

“Everything is looking great. Plants are starting to grow back. We love that all the schools are brand new, they have new equipment, new technology. My kids are going to school here, and they love it. Everything is new.”

Costs are still lower than in Chico and larger metropolitan areas like the Bay Area, though living costs have increased:

“It’s still rural, but it’s close enough to the city, and you get a lot of bang for your buck.”

After major wildfires, agencies such as CalRecycle (California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery) help with debris removal to take burned structures, ash, burned objects and the top few inches of soil in fire-footprint areas; the scale of the Eaton and Palisades fires transformed this process into a gigantic test ground of current technological means of dealing with the aftermath of gigantic urban fires.

Who’s selling, who’s buying, and who’s coming back

On a smaller scale, Paradise offers examples of what can be achieved at the community level. There are several individual examples of soil and ecosystem regeneration in the region affected by the 2018 Camp Fire. In addition to ongoing natural regeneration outside urbanized areas where structures burned along with vegetation, there are human-assisted efforts to improve soil health through seed and tree planting, as well as watershed protection.

Fires also open doors to radical turnarounds that often transform places and their former social fabric. But there are different types of opportunism, some of which are not as predatory as we might imagine. Consider, for example, Edwin Castro’s semi-sentimental bet. The winner of the record-breaking Powerball jackpot in 2022, Castro, who is from fire-ravaged Altadena and was formerly working on and off as a local mechanic, had cashed out the prize (a one-off lump sum of $997.6 million, paying $628.5 million in taxes) and had expressed he was willing to give back to his community.

After the Eaton and Pacific Palisades fires, he decided to invest in lots torched by the monster event. So, instead of focusing on his own house (also torched) and life while lecturing others to take responsibility for their own lives, like many virtue-signaling billionaires have chosen to do lately, he’s committed to a long-term project: a one-decade-long rebuilding project in its early stages of permitting and deciding over architectural plans.

Building back is already a colossal enterprise. But, given the constraints and the need of many people to return to their properties as soon as possible, building back better feels to many like a bit of a stretch, especially given the inflated rebuilding costs and the financial strain on those underinsured. In socio-economically diverse Altadena, corporate buyers have accelerated purchases in fire-affected tracts, which could transform the town and make it more homogeneous. Signs with words like “gentrification” and messages like “Altadena Not for Sale” have proliferated.

Combined, the Eaton and Palisades fires were among the most destructive fires in California history, with an estimated $95 billion to $164 billion in total capital and property losses, according to UCLA’s Anderson School of Management.

A city at work

But the burn zones are dealing with many more issues. In Altadena, the combustion of materials such as paint, wiring, treated wood, metal alloys, plastics, and various chemical products released heavy metals, which settled into ash and soot and have penetrated the soil after the recent rains.

About 90% of the homes in Altadena were built before the mid-1970s, before bans on lead-based paint, so many of the paints, plumbing, and structural components contained lead, asbestos, and other hazardous materials that were released during the fires.

Preliminary tests are discouraging, and California’s most vital frontier of innovation—one that could rival artificial intelligence—should be soil remediation, given the risk of fires affecting structures that include many hazardous materials, which, once burnt, contaminate the soil.

The magnitude of the disaster is staggering: over 11,000 homes damaged, nearly 13,000 households displaced, $30 billion in property losses, and an estimated total economic impact of $135 billion to $150 billion. In response, several state executive orders streamlined environmental and building code regulations to accelerate reconstruction and facilitate the quick removal of hazardous materials.

So far, the massive cleanup has set national records for both speed and scale: more than 2.5 million tons (5.5 billion pounds) of debris were cleared from burn zones within nine months—“the fastest major disaster cleanup in American history.” It’s the equivalent of removing 2,700 Olympic swimming pools’ worth of debris (by weight), more than the weight of 14 Empire State Buildings stacked together (from this perspective, I won’t look at any apparently sparse and leafy residential area the same way ever again).

There’s one main lingering concern, however: the lack of follow-up independent soil testing by the Corps to confirm that contaminants are within a tolerable range of heavy metals such as lead and arsenic. To ensure their place is safe, many property owners are conducting private testing.

The rhythm of soil composition

As a friend from Southern California recently told us, if there’s a place where people are wired to start over again after a black swan event, it’s Los Angeles. After the ash cools, the first signs of life are often green plants, which are nature’s chemists. Their roots, fungi, and associated microbes begin the long work of transforming inert, sometimes toxic ground back into living soil. Many people are aware of the risks associated with returning early to the area, yet they’re also willing to help nature heal through plant regeneration.

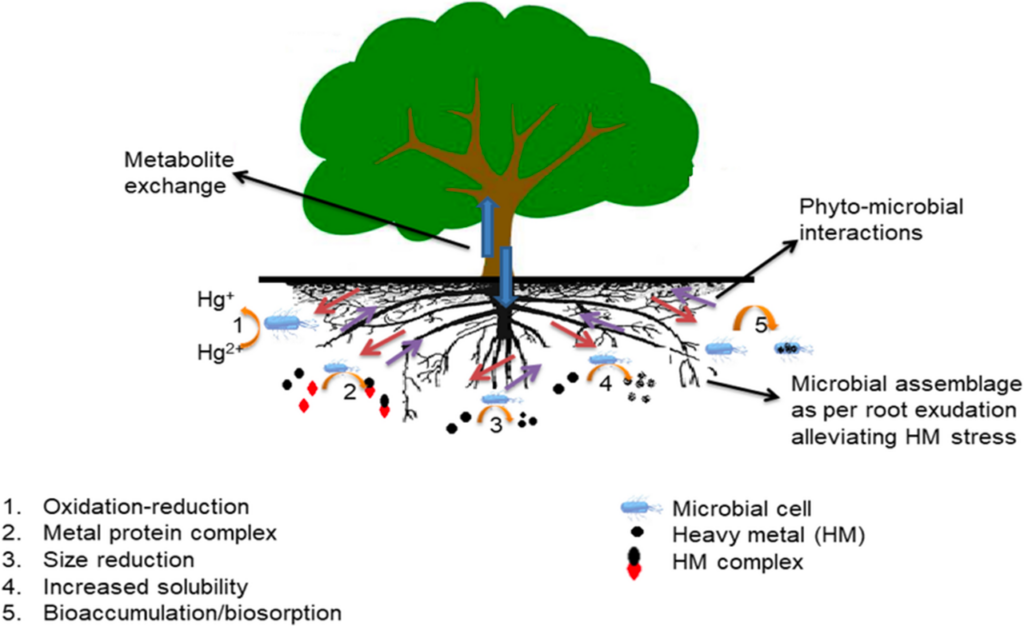

Much of this process will occur regardless. After a big fire in fire-prone ecosystems like the Southern California coastal chaparral, pioneer plants like fireweed, mugwort, and ceanothus grow everywhere and break compacted soil, allowing root penetration and aeration. Soon after, a patchwork of regeneration grows without us noticing much: fungal networks reconnect nutrient cycles, storing carbon and binding heavy metals. Process also known as: mycorrhizal awesomeness.

Once fungi have populated burned areas, a small but crucial collection of plants can be planted to absorb or stabilize contaminants, from sunflowers to willows. After some time, these decaying early plants feed microbes in the soil, lowering pH and neutralizing high alkaline soil (caused by “caustic” or contaminated ash), allowing humus formation.

It’s a process many imagine following the beat of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, while others see something on the lines of Death Cab for Cutie’s Soul Meets Body video clip, which is fun to watch.

Erik Ohlsen, an ecologist and permaculture designer based in Sebastopol, Sonoma County, says California’s native plants are especially suited to leading that recovery. I asked him some questions to include in the article, and he kindly agreed.

“California native plants have co-evolved with fire for thousands of years,” he explains. “In some cases even the viability of native seeds requires scarification from fire. Their roots drive deep into soils, allowing them to re-sprout once fire has passed. These living root systems hold soil intact, reducing erosion when winter rains arrive on fire-impacted sites.”

According to Ohlsen, many of these species also grow rapidly after fire, offering seeds, pollen, and forage for wildlife — an early ecological bridge between devastation and renewal.

A recent Smithsonian feature described how post-fire ecosystems often recover through “a choreography of roots and microbes,” reminding us that regeneration isn’t just spontaneous — it’s orchestrated by millennia of adaptation.

Ohlsen highlights that California’s riparian plants — sedges, rushes, and other water-loving species — are “bioremediation superstars.”

“They clean toxins from water and some may even accumulate heavy metals,” he says. “After fires, contamination of watersheds is a major concern due to toxic ash flow from burned houses and infrastructure. Having intact native bio-filtration systems such as rain gardens planted with these species can protect waterways enormously.”

He adds that fungi and bacteria “are of utmost importance for cleaning toxic, ash-laden storm waters,” and that simple systems can be built quickly using inoculated biodegradable straw wattles, straw bales, and wood chips — an accessible toolkit for communities working to safeguard their soil and streams.

After the LA fires, many locals have realized that scientific research can carry immediate benefits. Scientists and residents in Altadena have teamed to test ways in which native plants could speed recovery and soil regeneration. For example, recent research states that, when spaced around a home and watered, many local species (California buckwheat and sagebrush) help buffer against fire. But the research focuses now on these plants’ ability to pull toxins from contaminated soil.

Asked about the balance between letting nature heal and human intervention, Ohlsen points to context.

“Humans have been managing the land for tens of thousands of years,” he says. “In that sense, we’re part of the natural stewardship of the land. Post-fire or post-disaster, it’s vital that people play a role in regeneration when we can identify landscapes threatened by secondary disasters like watershed pollution or erosion. In those cases, human intervention is called for.”

But he cautions that not all landscapes need immediate human action:

“Where no additional hazards are present, allowing biological communities — plants, fungi, and animals — to repair ecosystems without interruption is often best.”

Soil removal vs. bioremediation

The chaparral vegetation of Eaton Canyon has a long and complex relationship with fire. It experienced a transformation as the urban continuum intermingled with the surrounding forests in Eaton Canyon and the San Gabriel Mountains. It’s coming back, and the charred land now sees the proliferation of shrubs that will likely blossom in full force from late winter to early spring, creating a unique wildflower explosion:

“California lilacs cover the hills in a deep blue. Manzanitas—fruit-bearing shrubs or small trees—show off their burgundy red trunks. And the delicate, white blossoms of chamise shoot up from beds of green.”

Though chaparral environments have evolved around fire events, it’s a myth that this Mediterranean-weather biome needs fire to renew or clean overgrown vegetation —The California Chaparral Institute explains.

Neighbors like Nina Raj, who moved to North Pasadena near Altadena to easily access nature from the city, are volunteering to keep seeds of native plants to share them with neighbors and help with plant regeneration.

Ohlsen warns against “aggressive responses” to fire that can do more harm than good.

“The biggest mistakes I’ve seen in post-fire restoration efforts come from over-clearing — removing trees that don’t pose hazards, driving heavy equipment on fragile soils, and hauling away biomass,” he says. “That carbon-based material is what we need to keep the soil covered, rebuild soil life, and reduce erosion.”

Following the 2017 Tubbs Fire in Sonoma County, he recalls, “thousands of yards of wood chips were hauled off the land right before a large winter storm. That material could have protected the watershed rather than being removed.”

Even the thin crust that forms on burned soil has a purpose, Ohlsen notes:

“It actually protects from erosion until adapted plant communities can regrow. Keeping machines off burned land until vegetation returns is often the wiser path.”

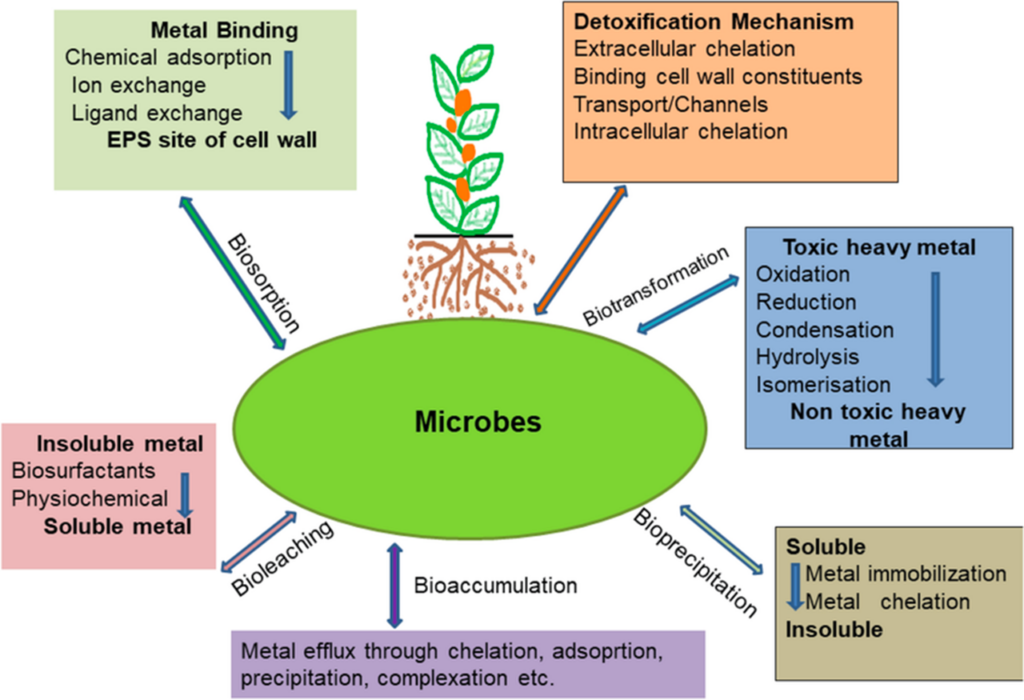

Roots, fungi, and microbes at work

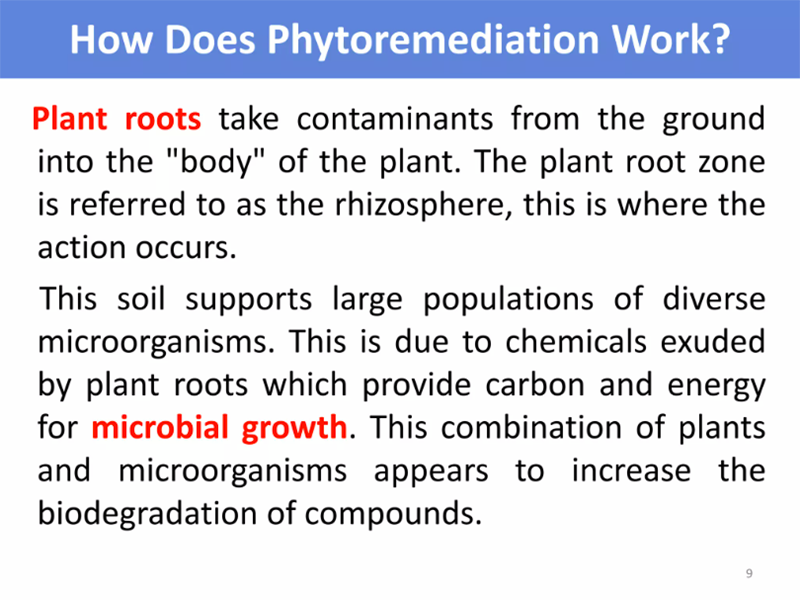

Proponents of bioremediation (or using plants, microbes, and fungi to detoxify soil contaminated with heavy metals) believe that their approach is more effective than the dig-and-dump method of soil removal, which also exacerbates particle dust.

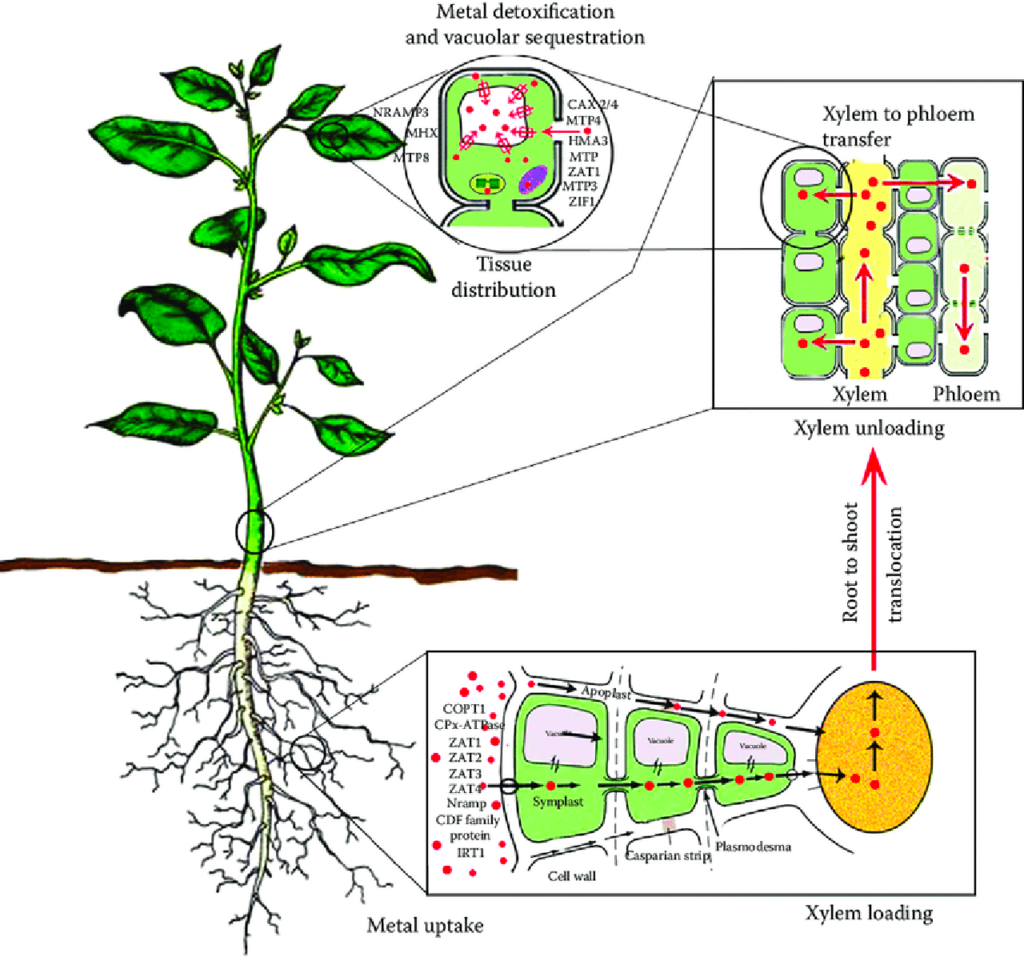

“As plants’ root systems take in water and nutrients from the ground, they can also pull metal contaminants, like lead, from the soil and store them in the plant tissue. According to Danielle Stevenson, an environmental toxicologist at the Center for Applied Ecological Remediation, this technique offers a more ecologically and economically sustainable way to heal soils.

“The dig-and-dump method, she says, is not only extremely expensive but also poses an environmental justice concern by often moving these contaminants into other people’s communities. Soil capping—another popular remediation tool that involves placing a cover, like asphalt or concrete, over contaminated soil—isn’t a great approach either, she adds, because contaminants stay in the soil and can risk leaching into the environment yet again.”

Bioremediation isn’t only cheaper but has a guaranteed long-term effect on the soil:

“Plants that conduct bioremediation are harvested and concentrated via incineration or controlled composting to remove the contaminants they’ve collected from the environment. The metals can then be disposed of at a far smaller mass than those removed via dig-and-dump.”

“Stevenson, who grew up near the Cuyahoga River near Lake Erie, historically a highly polluted area, has observed the way plants and fungi are able to grow in otherwise desolate polluted sites. In the LA area, Stevenson has led the way in figuring out which combinations of native plants and fungi best perform bioremediation in the region. She says that native plants are especially suitable for this task, since they’re adapted to the climate of Southern California.”

According to Mia Maltz, a mycologist at the University of Connecticut, native plants are well-adapted to local soil and microbial communities; in Southern California, drought-tolerant plants that thrive in the area have a deep root system that is especially efficient in absorbing toxins from the ground, even when contaminated fire dust has permeated the ground after rains.

Sunflowers’ superpowers

Locals like Lynn Fang aren’t waiting to act and, besides promoting plant bioremediation, have planted squash, corn, and sunflowers in the Altadena Community Garden due to the plants’ potential for removing toxins:

“Looking forward, Fang hopes to cultivate new connections with scientists, conduct additional research and share more knowledge with community members about natural ways to promote the health of their soils.”

Beyond native chaparral and sagebrush, some of the most promising bioremediators are humble plants that anyone can sow. Among them, sunflowers (Helianthus annuus) have repeatedly demonstrated a remarkable ability to extract heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic from contaminated soils — including post-industrial and post-disaster sites.

After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, fields of sunflowers were famously used to extract radioactive isotopes, such as cesium-137 and strontium-90, from surrounding soil and ponds — one of the earliest real-world tests of large-scale phytoremediation. More recent field studies — for instance, an experiment on mining tailings in Zambia — have confirmed that sunflowers can lower concentrations of iron, zinc, and copper within six weeks of planting.

Sunflowers’ high biomass, deep roots, and rapid growth make them ideal early colonizers of burned ground. They don’t just stabilize loose soil; they also feed microbial life and reduce alkalinity left by caustic ash, laying the groundwork for longer-term ecological succession. In California’s recovering burn zones, these “golden filters” are being planted alongside native perennials — a living interface between cleanup and renewal.

For Ohlsen, the future of land stewardship in California depends on a cultural shift already underway.

“Catastrophic wildfires, droughts, and the pandemic have all changed how people see landscapes,” he says. “A rising consciousness is taking root that we need an ecological approach to land management. Within that, there’s a huge opportunity to create local jobs and reinvigorate economies.”

He notes that during the pandemic many Californians began planting “food-producing, water-capturing gardens to ensure access to healthy food and water.” For him, these efforts signal a rediscovery of older wisdom: that “security and abundance can come from regeneratively designed landscapes.”

A new beginning

It’s almost poetic that one of the plants now cleaning Southern California’s post-fire soil is the same one kids paint in grade school—the sunflower. It thrives in the same scorched, alkaline ground where most other plants hesitate. Its tall stalks and heliotropic heads seem to mirror the human impulse to look toward the light again, even when everything around has burned.

The land, like the people who live on it, learns to heal in layers. The cleanup crews remove the ash and the toxins, but it’s the plants that bring the chemistry back into balance.

Bioremediation still feels in its early stages, as slow and imperfect as amateur gardening. But it’s proven its potential for soil regeneration and can be applied in those places neglected by the authorities, giving people the ability to act right away to improve the soil they’re planning to return to.

Soon, their gardens will be a testimony to regenerated soil.