In the first Gilded Age, fortunes found their conscience in public libraries and civic architecture. In this one, wealth seeks transcendence in AGI.

Many of us consider ourselves eager to see the benefits of technological breakthroughs, but things aren’t working as intended in a more innocent time for tech enthusiasts.

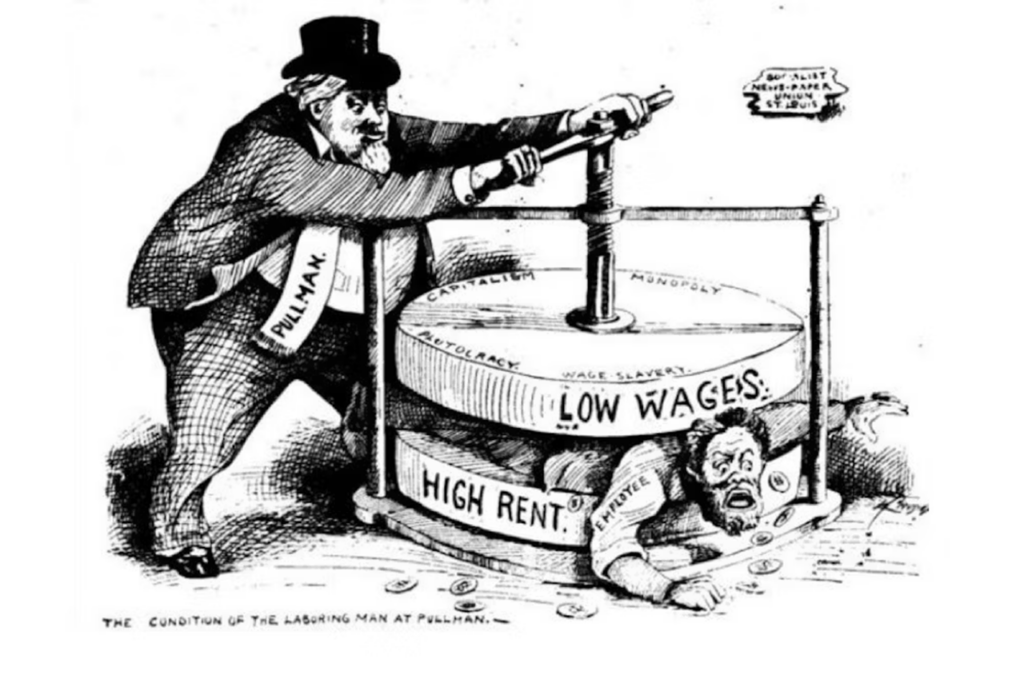

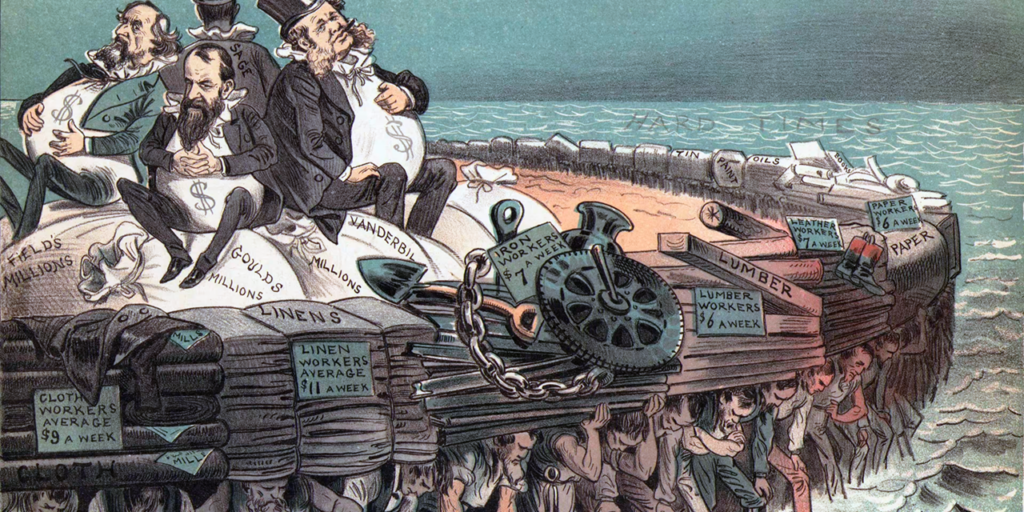

The parallels between our era and the Gilded Age can seem striking to many, and our reaction to it isn’t as defined by party lines as by one’s own conceptions of morality and tolerance for cynicism, for we’ll continue to see ostentatious wealth, rapid upheaval, and deep inequality.

However, unlike the late-nineteenth-century magnates and self-made dynasties, today’s moguls don’t have the same urge to make a significant impact on society and posterity through bold contributions to the commons, either direct (through taxation, donations, etc.) or indirect through genuine, consequential philanthropy.

In the past, philanthropy led to the creation of tangible assets: it founded and funded universities, built libraries, and developed entire infrastructures for the benefit of all (as opposed to today’s mechanisms for tax deduction, such as hollow foundations designed to park money).

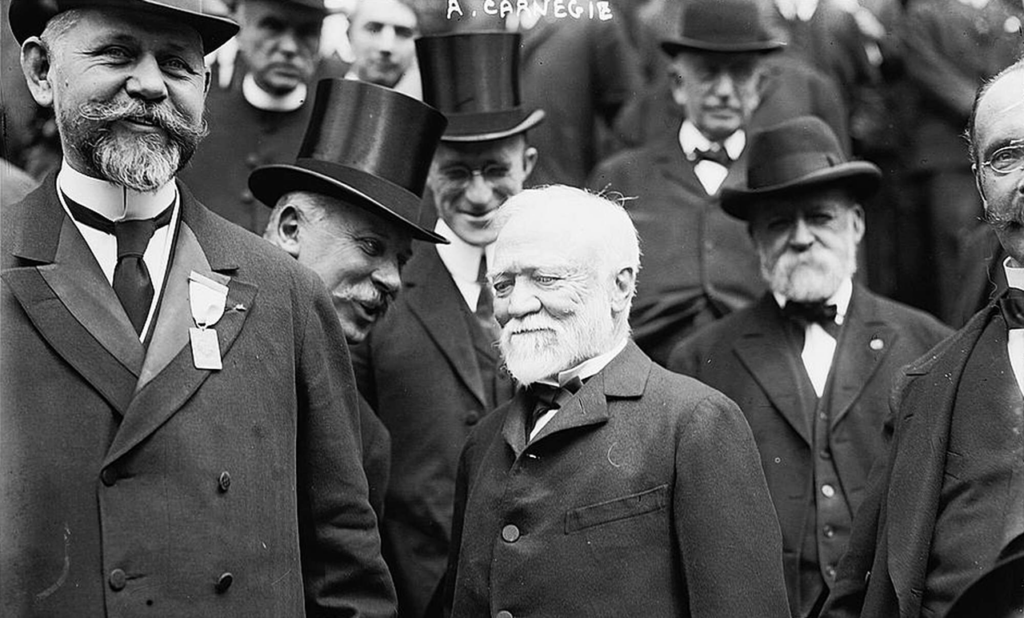

Andrew Carnegie funded over 2,500 libraries across the US, John D. Rockefeller founded the University of Chicago (1890) and Spelman College, as well as teachers’ colleges and medical schools; Leland and Jane Lathrop Stanford founded Stanford University and the surrounding town of Palo Alto, creating the geography and the very seed of the public-private joint venture that allowed Silicon Valley to flourish decades after. And so on.

Trust: the ambivalence of one word that built a city

When I read Hernan Diaz’s novel, Trust, a few months ago, I could see why it resonates in our age. Reading it feels like the same story being told by four conflicting, hallucinating chatbots in full metafiction mode, a depiction of one ultra-wealthy New York couple, each version more slippery than the last. The novel is a deep dive into the life and deceptions of an early-twentieth-century New York financier, modeled on figures from the Gilded Age, such as J.P. Morgan or Andrew Carnegie.

Above all, Trust is an interrogation of the intimate driving forces of capitalism, as well as the perception—internalized by many—that the American Dream revolves around financial success and its relation to virtue and destiny, a distillation of Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth.” Betting the farm in the Roaring Twenties might seem out of place today, but the circular multibillion-dollar deals to build AI infrastructure out of best-case-scenario predictions are, like the story depicted in the novel, a reckless push for disruption that wants to have its own doctored narrative.

Many things today remind us of the Gilded Age, though, unlike today, people like Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Stanford in California sought immortality through effective endowments to public institutions and the common good. Their philanthropy wasn’t purely altruistic for the sake of their Public Relations gains or tax exemptions; they wanted to be effective and pragmatic, building infrastructures to deliver maximum utility.

By contrast, today’s moguls seem more interested in building the digital temples of escapism for us all to depend on, not to benefit from; their monuments aren’t libraries but digital platforms to convert engagement into economic transactions that don’t follow one of the many paths that a more redistributive tech could have taken by encouraging people to create more value than one captures, both in access to the new tools themselves, and a fair chance to participate in the wealth created around the AI boom, now concentrated in private or quasi-private entities.

Roaring twenties’ party vibes vs. SNAP anxieties

Today’s world of post-mature capitalism is more interested in low taxation, financialized wealth, donor-advised funds (DAFs) that serve as vehicles for both tax planning and political influence, as well as building brand value with little substance behind it. Imagine today’s tech titans stating, like Carnegie, that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” Who knows whether it would be perceived as outright madness?

Technological improvement is making many people very prosperous, but the companies and individuals amassing the most significant economic gains as a percentage of the economy are a minority. A recent study by Harvard economist Jason Furman states that real GDP growth of the US economy has remained flat for the first half of 2025 (0.1% growth on an annualized basis) if the investments in data centers and information-processing technology aren’t factored in.

This disconnect is not new—but it has never been so measurable. The AI frenzy is essentially masking the economic reality faced by most Americans, a significant portion of whom may be supporting the current Administration. However, the investment in information-processing equipment and software in tech, primarily associated with the AI boom, accounts for 92% of the current growth. This parallel reality at the top is certainly making many people wealthy and transforming a few into the richest individuals in history.

It is a wonder that the current inequality hasn’t evolved into a Bastille moment (at the other end, we already have Marie-Antoinette-level parties, or in American terms, Great-Gatsby-themed parties, taking place while people can’t access their SNAP benefits to EAT).

It indeed feels like a very irregular bread-and-circuses moment. Though perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising when convenience entertainment is the only real “abundance” with a low barrier of entry in absolute terms nowadays, as digital entertainment reaches us in any imaginable way. Perhaps we aren’t amusing ourselves to death, but many are reaching levels of numbness that can distract them from what’s happening and instead point their outrage at marginal straw men like the so-called culture wars. Put in another way, digital entertainment not only prevents people from nurturing a shared sense of belonging but also magnifies tribal differences while diluting socioeconomic awareness.

Choose your own sycophantic chatbot

Perhaps people will choose their AI chatbot by prioritizing maximum utility, but there are already outright partisan versions of such tools feeding people what they want to hear. Choosing the Grok-powered online encyclopedia Grokipedia instead of Wikipedia can feel like switching from Google Maps to a treasure map that gives you dubious life advice—provocative, perhaps amusing at times, but useless and counterproductive if you want to know where you are and refuse to depart from a more-or-less reliable physical reality to enter a parallel world.

Of course, the internet and the supercomputers we carry in our pockets have brought us many benefits, from instant communication to telework and productivity gains. The AI boom can be as transformational as these two previous waves, and it may be even more so if we pay attention to the early signs of transformational change already underway and the possibility of reaching AGI soon.

A recent article by The Economist argues that AI tools could help people overcome the information inefficiencies causing them to spend more money on goods and services, from car repairs to home improvements, to any opaque contract preying on people due to information asymmetries. But we still have to see whether AI chatbots can help people bypass what The Economist calls “rip-off markets,” but the potential is real.

How this phenomenon, which made Nvidia the first company to reach a $5 trillion market valuation (surpassing the combined market value of most countries’ entire stock markets), will trickle down to society for the benefit of most people remains to be seen.

It’s happening

For now, the consequences are being felt in the form of efficiency gains through AI-assisted coding and specialty consulting, which is making it harder for many gifted young professionals to secure their first job. AI is already driving mass layoffs of entry-level white-collar jobs in tech, consulting, and finance.

Amazon is laying off 14,000 people in its corporate branch and plans to reduce its white-collar workforce by up to 10%. UPS has reduced its management workforce by 14,000 people in just 22 months, and Target plans to cut 1,800 such positions. There are many more examples: Microsoft, Meta, Salesforce, Accenture, Chegg, Klarna, Lufthansa, IBM, Procter & Gamble, and Intel (which has announced plans to cut up to 24,000 jobs, or around 15% of its workforce).

Interestingly, the Wall Street Journal reports that opportunities for front-line, blue-collar, or specialized workers are growing:

“Companies describe shortages of trade, healthcare, hospitality, and construction employees, while pausing hiring for consultants and managers, laying off staff in retail and finance, and deploying AI to do work in accounting and fraud monitoring.”

The real impact of AI is already underway. AI is already coming for some meaningful jobs and almost all the unjustified, so-called “bullshit jobs,” or at least all such positions not linked to nepotism. As for nepo jobs, they tend to persist, and the current environment may be especially conducive to them, not the opposite.

Even those of us who have embraced the potential of personal computing and the internet as a path toward human augmentation must acknowledge that, so far, many of the promised gains have been marginal for most people. Perhaps AI will force many well-educated workers with traditional access to status work into careers that aren’t only meaningful but have actual value beyond their social perception or economic compensation.

Bullshit jobs vs. AI-powered bullshit analysts

David Graeber’s pre-AI-boom (2018) concept of “bullshit job” identifies five main types of bullshit job: flunkies (jobs that exist mainly to make others feel important); goons (roles that exist only because others have them, often competitive or aggressive); duct tapers (people hired to fix problems that should not exist); box tickers (workers whose jobs exist to give the appearance of action or compliance); and taskmasters (managers who supervise people unnecessarily or create extra work for others).

Workplaces, such as those depicted in shows like The Office, reflect many of these dynamics. The rise of AI may accelerate the demise of such white-collar jobs; however, some argue that AI will instead reshape “bullshit jobs,” transforming them into new forms of busy-work. Some jobs that are meaningful (and highly compensated) today, such as building code or writing technical information, could be replaced by jobs in which people will “monitor AI” and perform “quality-control of AI outputs” instead of thinking independently, as they used to, mainly by leveraging their experience and intuition.

Chatbots and integrated AI tools are already building a new industry based on metrics, data-tracking, oversight, summarization of commentary, and “insights.” The new information formatting will require some time for humans to analyze, interpret, and appreciate. Instead of the end of “bullshitization,” we could be entering a new era of AI gatekeepers. Being busy, working on managerial hierarchy hubris, or living off status roles will not disappear for the privileged, but it may well disrupt internships and entry-level white-collar jobs, which are already being affected.

We’re already entering a wait-and-see period in which companies will determine in a rather Darwinian fashion what is valued as “human” work and what needs to be phased out. This time, automation is affecting the managerial class, and the affected incumbents will make sure that society knows what’s happening.

No wonder, then, that only a few remain naïve enough to buy into the simplistic theory of societal meliorism through “reason”—the Steven Pinker types, or those pitching “abundance” as a new panacea for progressivism, abandoning traditional stressors to avoid any redistribution scare (in other words, don’t do anything that threatens real estate interests or raises taxes on the wealthy)—and the idea that technological advance is bringing us closer to a genuinely more prosperous and advanced society.

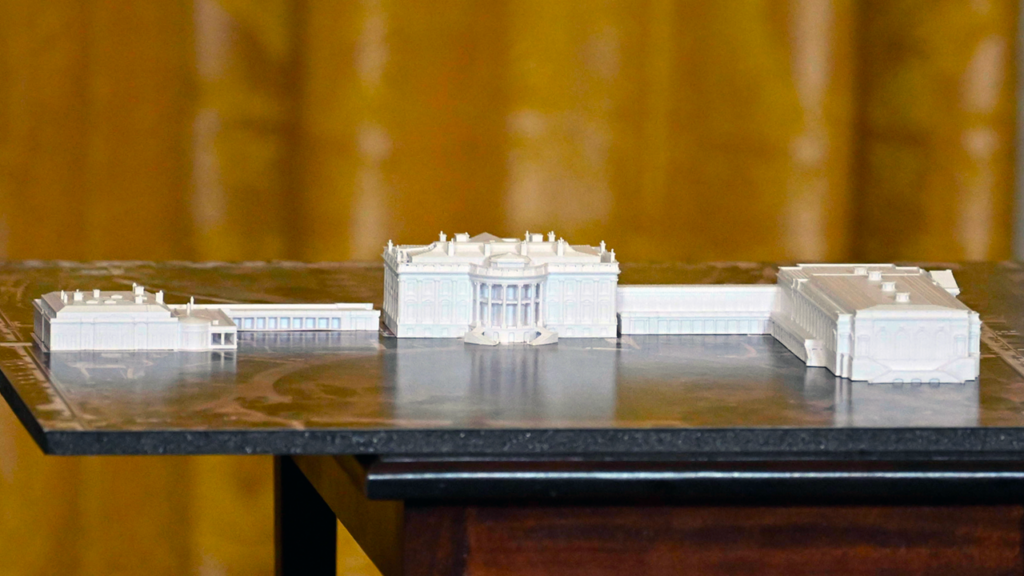

A ballroom dwarfing the White House

The White House’s East Wing demolition (and its planned rebirth as a grander, more ostentatious ballroom) feels like the architectural metaphor our era deserves: a warped echo of the great public works of the past, once funded by private wealth but built for the common good. That such spectacle proceeds while millions worry about the fallout from a government shutdown only sharpens the contrast. Perhaps the bulldozer, having crossed from metaphor into reality, signals more than a mere renovation —it marks the age itself.

Given the transactional character of today’s politics, it is no surprise to see the number of major corporations and wealthy individuals willing to fund the ~$300 million project, from prominent Tech firms and moguls to Defense contractors. Some convinced, some converted, some arguably spineless.

Traditional high-flying philanthropy focused on moral duty, civic uplift, “the public good” (or things people could use and benefit from, like universities, libraries, museums, parks); by contrast, modern transactional giving is all about strategic investment and tax exemptions, an important part of business and political calculus for influence and access.

Gilded Age fortunes have always been perceived as disproportionate; not anymore, and many analysts argue that today’s richest may have equal or greater power relative to the size and (especially) growth of the economy. The moguls of the Gilded Age were exploiters, but they understood that civilization required cathedrals. Our moguls build cloud servers to capture our attention away from the real world and call it progress. The question is not whether AI will bring abundance, but whether this abundance will ultimately strip the meaning and beauty from everyday things and serendipitous encounters among people.

Back to Hernan Diaz’s Trust (the novel, not the concept, though considering the concept’s ambivalence is key in life and in market sentiment, as Diaz plants in the reader): betting the farm in the Roaring Twenties isn’t conceptually much different from betting on today’s market with exponential tech. Back then, it was good ol’ speculation. Today is innovation. Two concepts that, together, play with the same equivocation of Diaz’s chosen title for his novel: “Trust” also as in “trust fund.”

Not a repetition, but it rhymes

Just as Trust asks who writes the story of wealth and power, Andrew Ross Sorkin’s recent work, 1929, revisits the speculative frenzy of the Roaring Twenties and shows how the same patterns (overconfidence, deregulation, narrative excess) keep resurfacing today.

Perhaps this time is different—back then, there wasn’t any regulation, and insider trading was a given among the powerful, who not only had access to asymmetric information but actively built the speculative reality (effectively acting as investment cartels).

We want to believe this time is different, and we’d better write it on the blackboard ad infinitum like Bart Simpson in the opening-credits scene of the series. AI is a tool that is transforming many aspects and adding real value to numerous human tasks, and there’s a case to be made about the staggering trajectory of many companies fueling this new stage in technology. But the unease is real, too.

Perhaps every technological revolution first overreaches before rediscovering the social instincts that make civilization worth advancing. The Gilded Age produced its barons before it produced its libraries. Maybe our own age, dazzled by its algorithms, will eventually tire of data and rediscover meaning — not in the pursuit of optimization, but in the creation of things that last and create real value and benefits for the many, and not the few.

AI as an opportunity

The question is whether this rediscovery will come through wisdom or necessity. Will we build new institutions of learning and art out of conviction, or out of crisis? The answer may determine whether AI becomes the opportunity to foster some sort of societal renaissance or another gilded cage in which a minority hoards access to a reality that feels like a parody at times.

In a best-case scenario, a group of rogue engineers and citizens might team up not to halt innovation in AI but to humanize its outcome, treating AI as a shared civic project or “AI Commons” designed less to replace people than to augment what people can do, which is the promise of the companies working in the field.

If the last Gilded Age ended with libraries, perhaps this one could end with information transparency and pragmatic workarounds that enable people to get better outcomes and fix the captive inefficiencies around them, like the mentioned article by The Economist argues, but also new forms of civic technology that return knowledge to the public square.