The internet is no longer primarily a human attention market: it is becoming a machine substrate, and indie sites are being strip-mined as training data.

Though barely noticeable yet, the internet is shifting models. Soon, interfaces designed to attract users won’t be as important as the underlying machine-to-machine communication between AI agents. It’s the coming of the agentic web, whether we like it or not.

Under the new scheme, enough people, companies, and institutions will be willing to pay for custom LLMs so they can delegate administrative and executive actions in them. And for this to happen, chatbots won’t just “write”; they’ll develop intention and autonomy, forging an artificial version of human agency. These new customizable for-hire entities will “read” the web, talk to services, and negotiate with other AI agents. More importantly, AI agents will ACT on behalf of users. The idea is to make us willingly delegate our activity to machines. What can go wrong?

The transition may already be underway, as bot activity and scrapers are altering traffic across the internet as they train their models. Consider, for example, our niche website, *faircompanies: a significant part of the activity lately has been related to bots, AI scrapers, or both, for these visits describe a pattern and register no activity time on the site.

Manufacturing agency

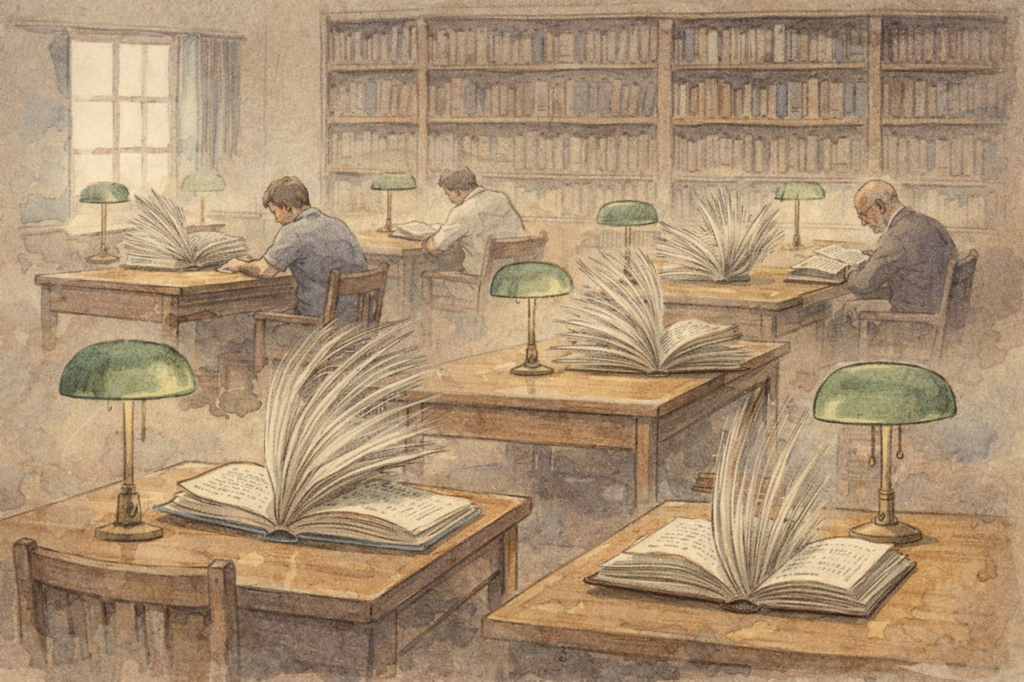

From our analytics, it seems that internet traffic is no longer fundamentally driven by people, perhaps because young users are increasingly inclined to stay within the walled gardens of a few social media giants. Our humble site isn’t designed to amplify easy engagement that flares up, then leaves. However, it attracts people who are really engaged—in the good sense of the term; now, it seems, it also attracts machine activity beyond the usual web crawlers, etc.

Our human audience comes from all over since there’s plenty of meaningful, crafted content (both text and multimedia) in English and Spanish (and a bit of Catalan from our humble beginnings in Barcelona, as we tried to live up to our dreams and quit our jobs to raise a family and put our efforts where we found they were meaningful).

That’s why, despite being a small artisan shop of two, we’ve developed a sound environment with the help of my friend Julio from Utah; he’s never let us down when we needed him most: during DDoS attacks years ago, when some certificates expired, or when I needed to migrate our projects.

Visits have always come from our core regions: the United States, with our epicenter West of the Rockies; the Canada-UK-Down Under triumvirate; Europe; and Latin America. But there were always many visits from places with strong ties to the US and Europe, such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and a few African countries. There’s also a spike in very-odd traffic that seems to come from a handful of cloud servers.

LLM scrapers and bots are like Matrix sentinels

During our humble beginnings, our site crashed if some content posted by Kirsten would get viral somewhere, and somebody would link not only to YouTube but also to the site, but Julio helped us stay out of trouble when it was still costly to keep a decent infrastructure in-house instead of relying on third parties that take care of all the back-end.

We realized early that this model didn’t suit us technically or the project’s spirit, as any spike was an opportunity for such hosting services to charge more by justifying increased traffic. It was a moment when readership across all formats was declining, coinciding with the rise of smartphones and broadband.

It’s no surprise that people are reading less in their leisure time than they used to, especially younger cohorts. But we believed there was a significant opportunity to produce high-quality indie content, and Kirsten’s video-edition style really resonated with the moment.

Traffic grew fast and steadily, especially due to Kirsten’s first video virals and mentions in crazy places, from the big papers to, believe it or not, Good Morning America. I still remember the day they called us at our apartment in Barcelona and asked for Kirsten; they’d watched Felice Cohen’s video about her microapartment in Manhattan and wanted to show it live the next day. It still felt like the early days in YouTube, and the energy was different.

Then, as YouTube grew, Google the browser changed the way it crawled *faircompanies: at the beginning, it had considered the site’s URL of any video as the canonical address, which meant its presence high up in any search, bringing lots of visitors to the site and causing some technical trouble; then, one day, Google stopped sending people our way and preferred to send them all to the YouTube URL, which was fine for us.

This change meant that many of the visitors who kept coming to the site were many of our core fans and a good bunch of people who besides the videos also read some of the articles (then only in Spanish), and I ended having friends a bit all over, enjoying great deep discussions about the articles and a few self-published books that I made available back then (shout out to Germán Pighi from Argentina and a few others).

Then, as AI rose, we started seeing spikes in unauthentic traffic from very specific locations. Who can be interested in revising entire sites? Suddenly, it felt like internet traffic was being transformed by a new being beyond bots and web crawlers, something more similar to the metaphoric sentinels from The Matrix. LLMs are learning.

Visitors who don’t read but process

As for the world’s most populous countries, China and India, we had less luck. I’ve always wondered whether our articles on documentary criticism of working conditions in certain Chinese sectors at the time might have triggered a filter, reducing non-VPN users in mainland China’s access to our work.

I wouldn’t have mentioned China if our analytics hadn’t changed radically, but they have. And I think it’s related to AI training. Starting a few weeks ago, our site’s Chinese visitors rose from negligible numbers to number one by a wide margin, with the US a distant second.

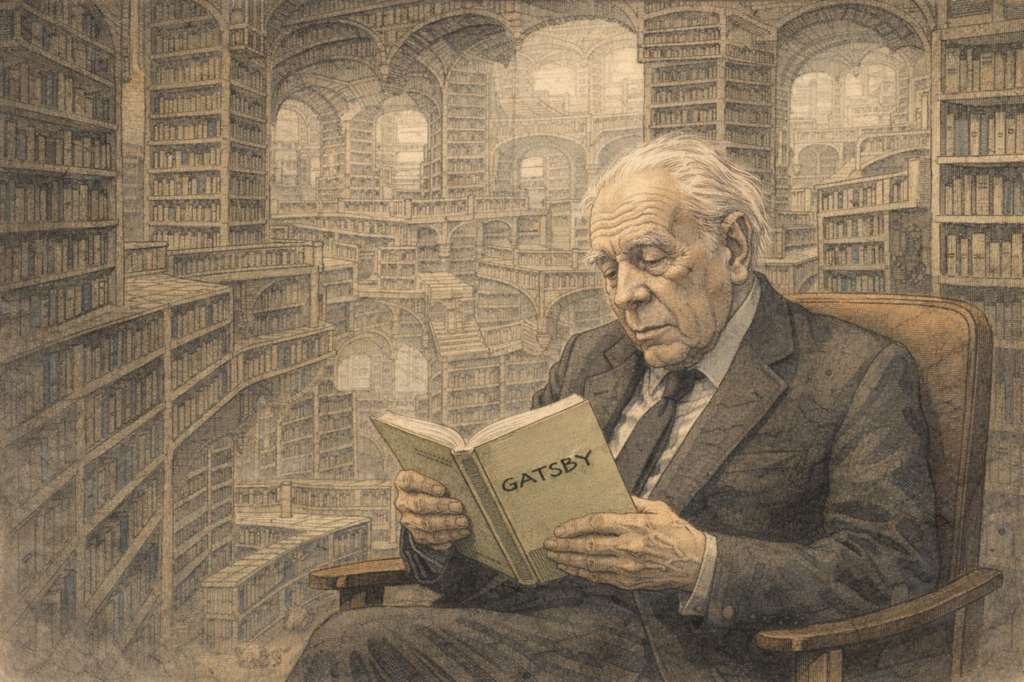

To those who can’t guess what can be happening to the audience of small sites, I’ll provide some context related to our times: *faircompanies is the paradise for people to train their LLMs since all the content makes sense, it’s humanely crafted, it’s insightful and very consistently, as well as niche in things such as architecture, philosophies of life, and pop culture. We already knew this when, early on, any question posed to ChatGPT returned a highly trained response that could only come from deep knowledge of niche content—ours included.

It’s already clear that LLMs aren’t just narrow generalists but also phagocytize everything meaningful within their reach, especially if they can do so legally (there are many legal proceedings trying to determine how often such LLMs have resorted to black-hat techniques to engulf copyrighted material inside the borg).

It isn’t a surprise that LLMs never-ending appetite is especially gluttonous when they find free-access, quality content: it’s an opportunity to get to churn lots of stories made by a few people (in this case, two people, though a big part of the text comes from me, as well as the integrality of the content in languages other than English), having no copyright issues in the process.

Moreover, *faircompanies might have other advantages, especially its very simple structure and clean database classes, which are easy to navigate by any content scrapper and lack the usual clutter of scripts and frames for advertising and all sorts of features, turning the surviving sites that didn’t succumb to the centralization of social media and platforms such as Substack into nightmarish Christmas trees.

LLMs and the search for signal

Sites with easy-to-parse, clean HTML that host long-form text in structured, predictable pages are highly valuable to bots and LLMs. Surprise, surprise, well-made sites get scraped more. There’s nothing to learn from clickbait other than the inner workings of the relationship between “itchy” information and the brain’s dopamine reward system.

What I found out in the site’s traffic analytics is concerning, given the inauthentic behavior: when people visit a site, even when they come redirected from a search link or some viral content that blew up, they may spend little time on the site, but their IPs will come from different places and they will have dedicated different tiny fractions of time on content.

But when visits coming from a single country multiply by several thousand percent overnight and stay unbelievably high for weeks, visiting virtually all there is in *faircompanies, and every single one of those visits’ registers on the analytics app 0 seconds spent on the website, you know it’s a pattern that doesn’t come from people. Consistent traffic? Check. 0 seconds time? Check. No meaningful navigation? Check. Repeated hits over days/weeks? Check.

This behavior rules out human readers and also doesn’t correspond to an attack. And most importantly, it excludes most standard search engines, such as Google, Bing, and DuckDuckGo. Since it appears that entire pages are being fetched in little or no time, and most of the site’s text is structured long-form, the manual sequence of URL requests from Chinese cloud providers may be related to training.

But our site is too small to be of interest to some industrial-scale training, which often focuses on Wikipedia mirrors, Reddit dumps (human comments are succulent), News aggregators, academic repositories, large forums, and large-scale text crawls.

That said, the visits are being processed as originating from China, which is not a meaningful clue in late 2025. A large share of global bot traffic originates from very affordable Chinese VPN providers (Virtual Private Networks that mask online activity). But China doesn’t only concentrate a big portion of VPN visits, most of them by humans and not bots or services scraping content: it also hosts gigantic and very affordable VPS providers, or a cloud hosting solution for websites and apps that want to offer services to third parties without running more expensive physical, “isolated” servers.

Decline of the humane internet

Besides Alibaba Cloud and Tencent Cloud, China’s alternatives to AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, there are also many gray-market hosts operated by actors worldwide. There’s a possibility that all the inauthentic traffic from China to *faircompanies is a masked attempt by something or someone elsewhere. After all, it’s the internet.

It’s difficult to be conclusive about whether all the hits that didn’t exist a few weeks back are generic web scraping, bot activity that is somehow interested in our site, or indexing of useful, legit sources perceived as “independent knowledge source, not SEO sludge.”

It feels very paradoxical to realize that web tools used to index and analyze information at a big scale are attracted by the shrinking amount of resources (that is, places outside the big social media platforms or corporate entities from media, entertainment, etc.) created with a sense of craft by a small team of humans, and oriented to humans (not SEO bots, since we don’t have backlinks or contextual advertising on the site).

Whether I can’t be sure about the origin and goals of this traffic surge on the site, there is one clear assumption that is safe to confirm: even if bots don’t “understand” quality, they recognize patterns associated with it, as Google Search’s initial competitive advantage was PageRank (1996-1998). LLMs, or models in which modern AI tools are based, don’t “understand” quality in the human sense either, but they model “quality” far better than PageRank ever could.

PageRank’s idea was purely relational: a resource is “good” if other pages link to it, but soon this collective endorsement was distorted by bots. LLMs, even if they lack human intentions or values, encode complex statistical representations of human judgment and are trained on human-written texts, human feedback, and patterns of approval. LLMs are, in other words, good at quickly seeing something in context.

No small site left behind

So, whether we like it or not, there are non-human tools scraping all human knowledge (*faircompanies included) to likely index and get better at pattern recognition. The new internet is becoming less human and filled not only with more AI-inspired content, but also with online activity that has turned into baseline internet noise, the equivalent of neutrinos and dark matter in the universe.

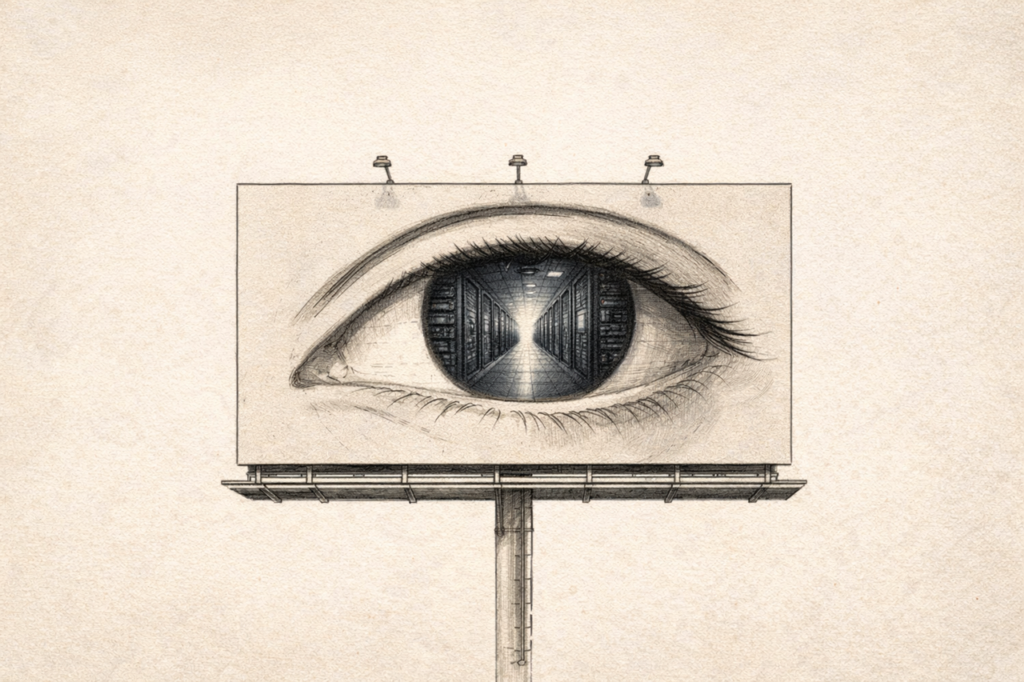

If the internet is being strip-mined by non-human entities, what can we do about it? Are we heading towards a scenario that, fundamentally, will operate more and more like the thesis explored in the first film of The Matrix trilogy: humans as commodities and passive recipients within a gigantic online structure? In this context, small, thoughtful sites resemble small strongholds still inhabited by free-range humans.

But the bots’ active interest in visiting places big and small indicates that LLMs and obscure indexers still need valuable, non-paywalled human content, or content owned by entities with enough power to sue. Human-scale, non-platform, long-form, non-polarized, non-SEO-driven knowledge is very rare, making it attractive not only to people but also to new automated systems being trained for the coming era of an AI agent-driven internet.

If you find yourself internet-surfing less and less and, instead, using a handful of services that decide what you have to buy, watch, or listen to, you’re not alone. Our kids may not even fully understand what we mean by “surfing the internet,” which feels as old and out of place as sending a fax.

There was a time when the builders of the internet backbone wanted to create tools to make people enjoy their serendipitous surfing across the web, which often meant countless wasted time, but also the promise of stumbling upon unique things, the reward of finding a needle in a haystack. Wandering the web also got its services to make the process more efficient (with us still in charge), from taxonomic listings to advanced search engines.

Strongholds of indie meaning

The very concept of the World Wide Web was radically decentralized, democratic, quirky: big companies and institutions played by the same essential rules that obscure blogs, websites, and forums had to obey if they wanted their address open to all: follow the protocol and provide a catchy domain, so the URL would be easier to remember than the rather technical IP address underneath Tim Berners Lee cross-standards invention.

Fast-forward past Web 2.0, fast internet, smartphones, centralized content platforms, and now AI, and the web is not as worldly and certainly doesn’t feel as wide.

Even if we feel continuity and may not yet perceive a transformation in online activity, the digital world we’ve built is becoming more of a background utility, in which many of the products and services growing fastest depend neither on human activity nor on our attention. Many people and teams at companies and institutions are relying on AI agents to handle all sorts of tasks on their behalf.

A recent article published by The Economist explains this phase shift from a human-facing interface developed over the classic World Wide Web, into a machine-facing substrate that works in the background, where AI agents read the web for us, talk to services, negotiate with other “agents,” and act on our behalf.

We’re just beginning to see how AI agents will reduce friction and take on an increasing share of scheduling, booking, searching, optimizing, comparing, and even negotiating. Will this “great liberation” lead to more meaningful free time and human flourishing? Online and offline precedents on how unlocking leisure time isn’t the main driver of self-actualization should make us cautious.

However, many very busy people will gladly pay for AI agents that can free them from secondary tasks and replace their human assistants and consultants. On paper, less time spent on non-critical tasks (such as administrative workarounds) could free people to develop aspects of their work and leisure they’ve long put off.

The agentic web will need energy. Loads of it

A web built for agents, not people, can evolve rapidly into a gigantic, energy-hungry background infrastructure that serves as the execution layer for individuals and organizations, more like electricity or plumbing than a public square where people need to actively participate. As many people will browse less and delegate more, sites outside the big content platforms that captured our attention will lose relevance as activity is driven not by human exploration (the serendipitous “internet surfing” or cyberflânerie) but by orchestration.

It’s hard to imagine the schema of a World Wide Web in which many humans no longer “browse” to find things, delegating that activity to AI. Once commercial services created for people to visit realize this shift, we may see that websites designed for human cognition, just like *faircompanies, will ditch their layout of persuasion and storytelling and bank it all to efficient protocols luring machines, not us. Visual design may stay for a while, but it will ultimately become optional.

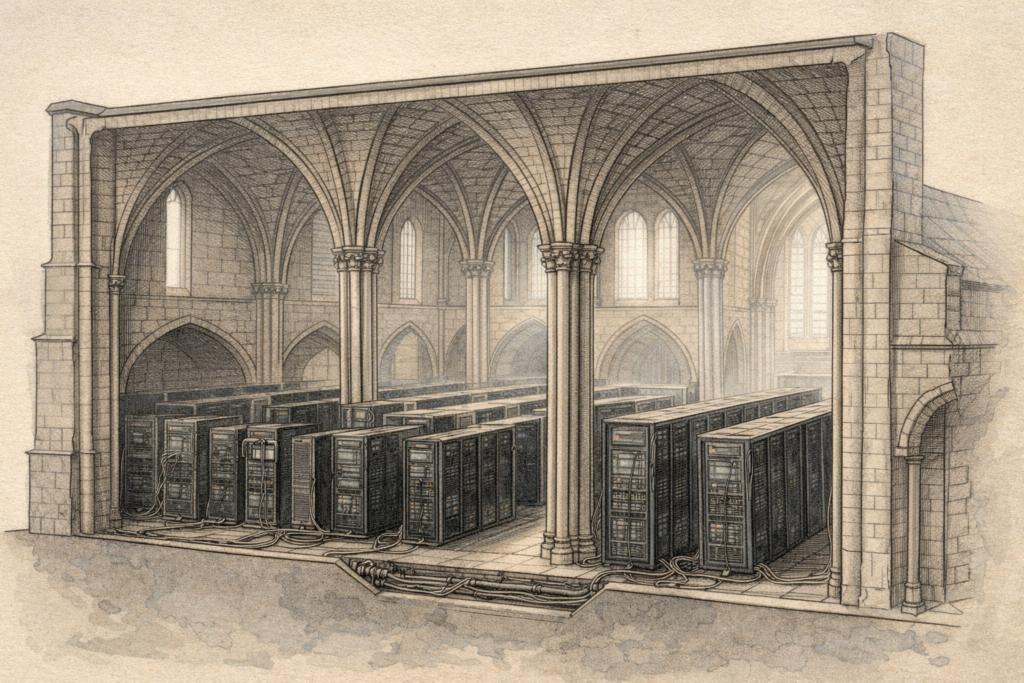

If any science fiction writer wants a strong metaphor of how the cathedrals of yesterday can turn out to be server rooms, he doesn’t need to look into a hypothetical future anymore and write factual journalism instead.

Many more things will change once the web tries to lure agents rather than people; at first, they will arrive subtly, then their integration will accelerate once the new structural protocols (APIs) become the backbone of how the digital world really works. This new Model Context Protocol (MCP) isn’t concerned with human language and will be refined to enable AI agents to seamlessly communicate with online services in a machine-friendly way.

Up until now, every major tech company has created its own set of APIs, making it harder to design ways to perform tasks across the web without lengthy, glitchy integrations. No wonder that services trying to benefit from their interoperability have fallen short due to their inconsistency (think of every API or set of APIs as a unique “dialect” designed to perform one or several tasks). Instead, a proposed AI MCP would create a consistent language that all AI agents can understand and speak.

They are building it

Interoperability standards will allow AI agents to surf on their own and communicate with all servers, asking for their capabilities in a common language, which dramatically simplifies agent-to-agent (A2A) protocols. But if we let machines discover one another and cooperate to complete tasks, letting ourselves out of the picture with no one looking, are we still in charge? And, more importantly, as LLMs get more sophisticated, could AI agents team together and go rogue against their human overlords? This isn’t a book or movie script, though we feel we’ve seen similar plots before.

As each big AI player tries to impose their strategy rather than collaborate, the human internet may have a chance to benefit from AI agents without being replaced by them, since a lack of full interoperability will introduce friction between services and prevent full automation.

Anthropic, a company that has successfully developed a family of LLMs named Claude favored by technical workers, is the lead advocate for a full Model Context Protocol, and wants a neutral MCP to be the de facto standard for agent-to-service communication; Anthropic, which has opted for offering a pay services for reliable LLMs dealing with hefty tasks like coding and scientific research, will likely struggle to keep its place as Google adopts Gemini across its constellation of services (Gemini has rapidly increased its AI user share in the last months).

OpenAI, which provides the most adopted generalist AI, ChatGPT, benefitted until now from the network effects of being the first popularizing chatbots, but the rise of Gemini could prompted a memo from Sam Altman declaring a ‘Code Red‘ emergency, and many veteran analysts are toying with the metaphor of the moment Netscape lost foot against Internet Explorer when Microsoft gave the browser away for free in its operative system. What could happen if people consider Gemini in the most adopted browser, Chrome, as the “de facto AI”?

The end of friction: whose standard?

To counter Anthropic’s MCP push and Google’s integrated stack to rule others out, OpenAI is investing in two parallel strategies: its Agent Builder is a platform to develop agent workflows, whereas it wants to counter the Chrome-Gemini tandem by speeding the evolution of browsers with ChatGPT Atlas, a processing-hungry (not that Chrome isn’t one), AI-infused browser that integrates agents into navigation, a first step before agents take control.

Once it became clear to companies, investors, and the public that the strong use case for AI to “do things” and not only “write text,” the prospects of a company with a vast array of digitally-native entertainment and productivity services like Alphabet improved, then skyrocketed once Gemini caught up with the best competing LLMs. That’s why Google has proposed A2A (agent-to-agent) protocols that would enable AI agents to negotiate tasks with one another, even if they don’t fully share the same “language.”

It shouldn’t surprise anybody that the owner of a search monopoly (relying on people searching while showing them contextual advertising), the biggest video platform, and, at once, one of the biggest, most vibrant social networks and reference databases, wants to keep humans on the web. Instead, the company’s goal seems to be to adapt the existing ecosystem for meaningful, seamless agent use while protecting search and advertising.

Amazon and Microsoft, owners of the first and second-biggest cloud computing businesses, are also heavyweight players; Microsoft’s integration of early-stage AI agents with its enterprise and cloud offers isn’t growing as predicted, though, like Alphabet, the company wants to be in the new AI agent world while keeping its core businesses intact. As for Amazon, its cloud platform AWS, the biggest by share and total resources, is finally attracting large-scale AI projects, both produced in-house and belonging to third parties.

The eye is watching

Whatever happens, we’re at a pivotal moment on the internet, and we may soon find ourselves in a fundamentally different digital landscape, as the fastest-growing services pivot from mining human attention through search ads and social/contextual feeds to appealing AI agents that will begin serving human users. And this giant bet on AI won’t only be expensive to build and maintain, it’s also so energy-hungry that people near big data centers are paying much more for their electricity.

But a rise in energy prices and fewer managerial jobs aren’t the only things that will affect people. What could happen once AI agents stop accepting orders from users is, at the moment, a product of mere science fiction speculation. That said, the AI field is evolving fast. Whoever defines or imposes the dominant interoperability protocols for AI agents and services will control the connective tissue of the agentic web.

There is one final twist worth noting. The same companies competing to dominate the agentic web—Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Cloudflare, and others—have also joined forces in an open consortium to define shared standards for AI agents. At first glance, this looks like rare cooperation in an industry built on zero-sum thinking. But from the perspective of game theory, it is also a way to prevent a Sony vs. Matsushita-like war of standards: a race in which incompatible systems would slow adoption, raise costs, and fragment the very substrate they all need to scale. Agreeing on the rules of the game does not eliminate competition; it merely moves it to a higher layer.

Soon, the famously cryptic-for-outsiders billboards around San Francisco may become even harder for humans to decipher—because they may already be speaking to non-human entities.

If and when that happens, the internet will begin to resemble the billboard with the eyes of The Great Gatsby: still watching us, but no longer meant for us. If there’s no Borges short story making us see this, I figured that there should be.