The tools changed from axe and almanac to solar and smartphones, but the old wager remains: live deliberately, outside the script. Sort of.

Over the last few years, Kirsten and I have noticed and helped document the growing interest in leaving the constraints of contemporary urban and suburban life and starting afresh on a frontier that now exists more as an idea than territory.

The itch to drop out of a hyper-competitive and hardly rewarding fight for expensive resources around hotspots isn’t new. We’ve also paid attention to people whom we consider true pioneers, like Lloyd Kahn, because they successfully created their own alternative lifestyle decades ago.

Or, like Socrates saying (as reported by Plato):

“Employ your time in improving yourself by other men’s writings, so that you shall gain easily what others have labored hard for.”

As he’s explained on his Substack as a context for his latest book, an autobiography (titled, like the Substack, Live from California), Lloyd “dropped out” a long time ago and focused on creating small homesteads in the few unincorporated areas still available back in the sixties, documenting the process along the way (and similar lifestyles from other people across the US and beyond) for anyone interested to benefit from.

Tuning into one’s own wavelength

This isn’t an entirely American phenomenon; proof of that is the network of friends we’ve visited across Northern Europe (Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark) and Western and Southern Europe, from France’s Vosges region to Northern Spain and the Italian Alps, to name a few.

Unlike what many people think, many of these homesteads have humble means and start with little. Bolinas, the quirky unincorporated coastal town across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, is still secluded today, protected by undevelopable natural areas, marshes, and tiny winding roads that increase the time to get there, but this natural “friction” to get eaten up by convenience (and hordes of daily San Franciscans) didn’t prevent the place constrained by a limited number of water meters—which give the right to develop a lot—, to become an expensive retreat town peppered with a few original survivors, Lloyd Kahn among them.

We’ve had the privilege of visiting Lloyd a few times at his Bolinas place and have seen with our own eyes, and through Lloyd’s unique hands-on approach, how his place evolved from an early dome into a self-designed and built, cozy and sturdy craftsman-style home. Lloyd was, after all, the main US dome expert during the sixties, as the building editor of Whole Earth and the subject of a retrospective on the topic by Life Magazine, both publications sort of the YouTube of the 40s-70s.

Also, like good science, he was also ready to learn from experience and failing conjectures, so the many failings of domes (among them, sealing and water filtration issues, as well as difficult-to-solve layout conundrums) encouraged him and others to follow other paths. Now, some builders and small companies believe that new materials and processes can help make domes relevant again.

Not a lifestyle accessory: beyond weekend ranch aesthetics

As for the potential frugality of homesteads, if they’re built in affordable, unincorporated areas with few construction constraints beyond basic safety and common sense, even before YouTube, many people found a way to create their own self-governed utopias, often thriving along the way.

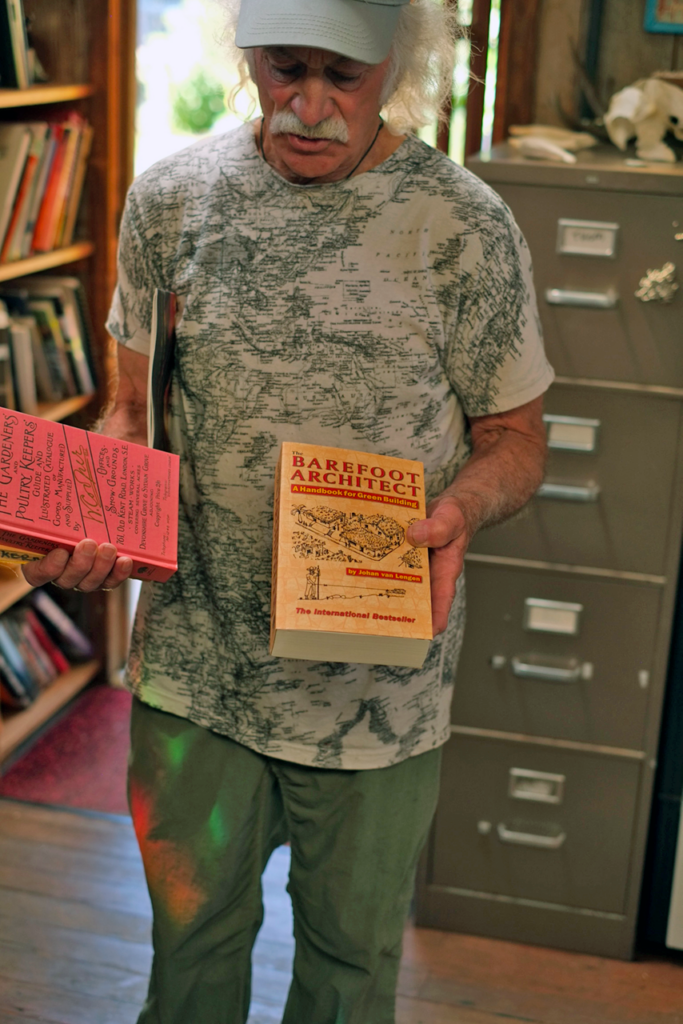

Lloyd Kahn helped along the way with his own books and the ones he bought and published, like Johan van Lengen’s The Barefoot Architect. Other independent writers and editors also offered their experience in indie books, like Mike Oehler, aka Mountain Mike, a Chicagoan who moved to the Bay Area in the 60s and left the place in the 70s, settling in the Idaho woods and writing provocative manuals such as The $50 & Up Underground House Book (1978) and The Earth Sheltered Solar Greenhouse Book (1981).

We were lucky to visit him a few years ago, We’ve also visited pioneers who made their impact on little money and humble beginnings, like Norcal’s Charles “50-years-off-grid” Bello, and heard from Lloyd Kahn and others about people such as Sunray Kelly and his Pacific Northwest homestead, and have spoken with his widow several times after his passing.

Many inspiring examples go beyond a “start-to-finish” sped-up TikTok or Reels, and stories of people who’ve chosen how to live fulfilling lives with little currency worth of contemporary society and an abundance and the currency they most care about: intention, the use of time on their own terms, healthy food, time to exercise or read or follow their hobbies and passions… And yes, with the arrival of social media, some of them have successfully chosen to advise others, and become successful even in terms sanctioned by “respectable” citizens, often (paradoxically) less successful than they are. Though these are a few, and many of the people whose real intention is to monetize their alternative lives from day one, give up if things don’t take off after a while.

Many of the (often ex-urbanite) homesteaders we’ve encountered along the way also follow a pattern that we couldn’t help but notice. At the source, there’s an intuition of being unfit to the speed and lack of authenticity of an urban life surrounded by convenience (read: “products and services you have to pay for, lately as a subscription”), and the realization that, surrounded by superficiality, they end up living a life they didn’t intend to. Again, this isn’t new, and Thoreau’s Walden (and his famous quote, “I went to the woods…”) turns around the same premise of living deliberately.

Not about getting there first, but to start and keep going

Things have sped up since Thoreau, when he noticed the speed of things due to the railway he could see and hear passing nearby. Thoreau was an avid press reader and, by the time of his experience in Walden, he was certainly aware of the AI of his time. He’d built his cabin and lived at Walden Pond during 1845-1847 and published the book in 1854. Samuel Morse’s first practical telegraph occurred in 1837, and the first successful long-distance line (Washington-Baltimore) was installed in 1844.

The telegraph was already expanding across the country from the late 1840s to the 1850s, and he was aware that the transcontinental telegraph was on the way as well. It did indeed come in 1861. The telegraph makes us laugh as of now, although many people were self-aware that it was just the beginning of an acceleration process that is experiencing another hyper-acceleration. And, when such things happen, many decide that it’s not for them to adapt to a new dynamism that demands more (not less) from them, often with less pay involved compared to the cost of living—that is, if there’s not a forcible adjustment through laws or big shocks, like wars.

Those trying to diminish this fundamental lack of sync between many people’s authentic wishes and the lives they think—or are encouraged to believe—they have to carry, believe this isn’t but just a fad, often incentivized by social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram. Even if this is partly true, and many people opt to try to compensate their sudden lack of income by documenting their new backcountry lives, many people aren’t there for the potential exposure and remain private, often willingly so, even if they truly could benefit from showing what they’ve achieved. We’ve seen many of these examples all over the USA and Europe.

It isn’t for everyone, but many of the ones who try never look entirely back, and when they do so and return to a competitive urban life, do so with a different perspective of material life, and a different cognition, aspiring to live with more intention and less superfluous convenience (aka debt anybody could afford to avoid without truly diminishing their quality of life, and sometimes increasing it as a consequence of cutting back to the essentials).

One constant American trait: love of practical engineering

Insiders like Lloyd Kahn have been advising some of these self-conscious, non-destructive modernity dropouts by showing how it can be done by offering designs and cultural context, either self-built or self-built by others, from his seminal, raw 1973 “Shelter,” to the hyper-practical (and code-controversial) The Septic System Owner’s Manual.

Many years before YouTube, and when institutional book publishers and magazines focused on abstract and mainstream topics, editors and mailing lists kept the conversation going from a hands-on, practical engineering perspective, thanks to the Whole Earth Catalog, Shelter Publications, and local alternatives.

Of course, there are also the cults and the Ted Kaczynski types, who, instead of choosing their lives, decide that their fulfilling existence is to destroy other people’s lives. And those who buy raw land and, after dealing with insects and off-grid sanitation for a week, decide that the ordeal isn’t for them.

But to dismiss the trend as some sick conspiracy of asocial incels and hikikomoris (young adults withdrawing from social life), like somebody suggested to us at a book presentation at the Berkeley City Club (an elder man, grumpy and probably a big house owner, keeping his equity thanks to Proposition 13 as he awaits for immortality), is to miss the underlying problems of contemporary society.

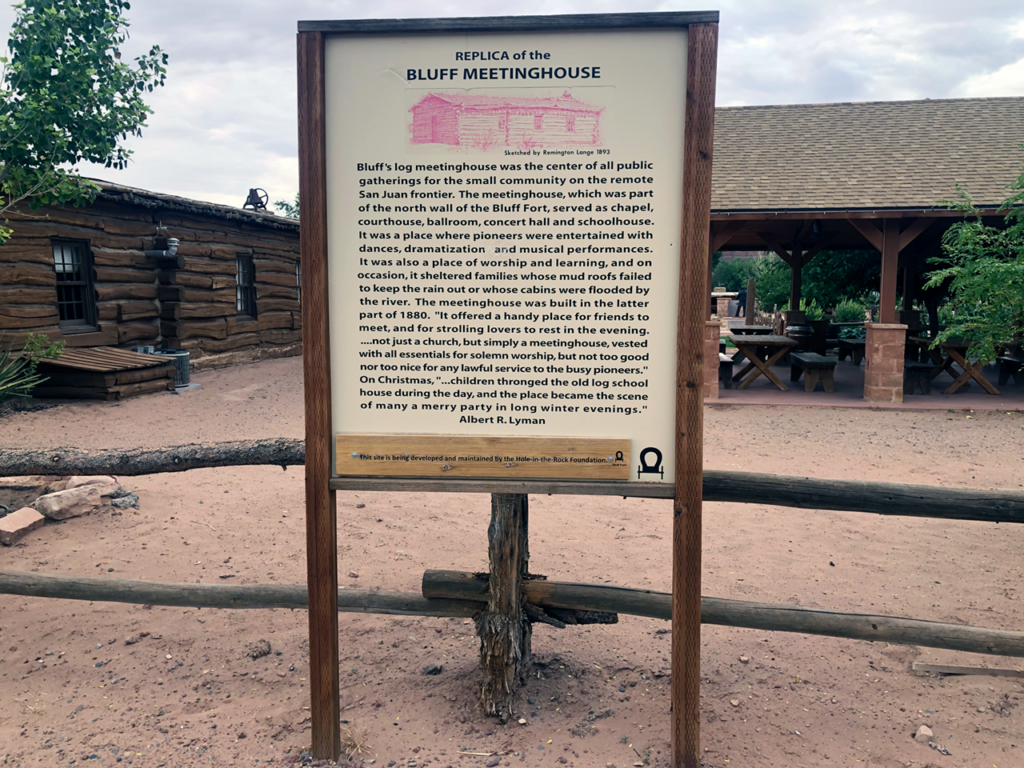

Even the complaint that homesteading is “solitary” misses something important: community is not exclusive to dense cities. Ivan Illich had a word for the social richness that can exist outside institutional life—conviviality—and it often shows up not in the metropolis but in tool-sharing, neighborly labor, and the necessity of mutual aid. We’ve met many homesteaders who are really intertwined within their local community, often helping maintain common areas and knowing when to ask or give a hand. In remote areas, there’s a sense of solidarity long lost in transactional, dense places.

Perhaps, this participant in our event at Berkeley would like everybody to live in their own two-bedroom craftsman-style on 1/16th or 1/8th of an acre, but don’t tell people who bought in the seventies to pay more property taxes or move on to a smaller home to contribute to a more dynamic housing market in one of the most expensive places in the world to live. You got to love the bug of self-righteousness that gets onto people’s systems as soon as they become homeowners.

I wonder if we all realize that homeowners are, overall, deeply conservative in many decisive matters (like housing), preventing younger generations from having a fair chance. Nobody is asking for more, as far as I’ve heard. I’m curious whether this person read any news explaining that Americans aged 55 and older control approximately 73% to 80% of the country’s wealth. They have been going around lately.

It’s not avocado toasts and digital subscriptions: being young today

Places across the West, especially California, were once among the most dynamic regions, benefiting from upward social mobility. The United States as a whole isn’t the best place in the world to enjoy a fair chance at overall intergenerational mobility.

More than 90% of children born in 1940 went on to earn more than their parents did, but this phenomenon reversed from the 1980s onwards. At the same time, the “Great Gatsby Curve,” or greater inequality linked with lower mobility and fewer chances to prosper and eventually own a home and increase capital wealth not directly related to income, has skyrocketed. If we look at the American Gini coefficient (grade of inequality within a population, ranging from 0 (total equality) to 1 (maximum inequality), the US ranks among the most unequal developed countries. And so, if the French Revolution registered 0.6 on the Gini coefficient (very high), the US currently has higher inequality.

But I want to bring this article back to the woods—and to the quest by some to live deliberately, or at least to find out what that means. To many, it first means that watching a bunch of short videos that show a process that looks easy doesn’t tell the whole story. Raw, abandoned, unproductive, unincorporated land has to be purchased, and—at least in the US—if one has to pay little, this land will be far from big cities and coastal states.

Many also realize that, even when they find a place they like and want to purchase, picturing themselves in it, they underestimate the unknowns, especially if the goal is a mostly moneyless, DIY endeavor rather than relying on workers and volunteers or barn-raising parties. There are those who realize that the place they moved to is harsher than they expected, with freezing winters, unbearable summers, or both.

Even those who realized that Hawaii’s Big Island is still comparatively cheap, the places where raw land for sale abounds at very low prices are next to lava zones and/or areas where it can rain for weeks at a time, affecting any outdoor activity (perhaps the main goal of many moving there), and one’s mood. It’s the case of the island’s south-east from its main town, Hilo, to Kalapana. When we spent a week there a few years back, we saw little sun, and at times it felt colder than the thermometer indicated. “Tropical” doesn’t come in just one flavor.

First Homestead Act

Similarly, we’ve also traveled extensively across the borderlands of the US Southwest, where lots are for sale on the cheap and offer livable conditions from late fall to early spring, but push residents inside air-conditioned environments for at least half a year. The desert, or even the colder high desert, isn’t for everyone either.

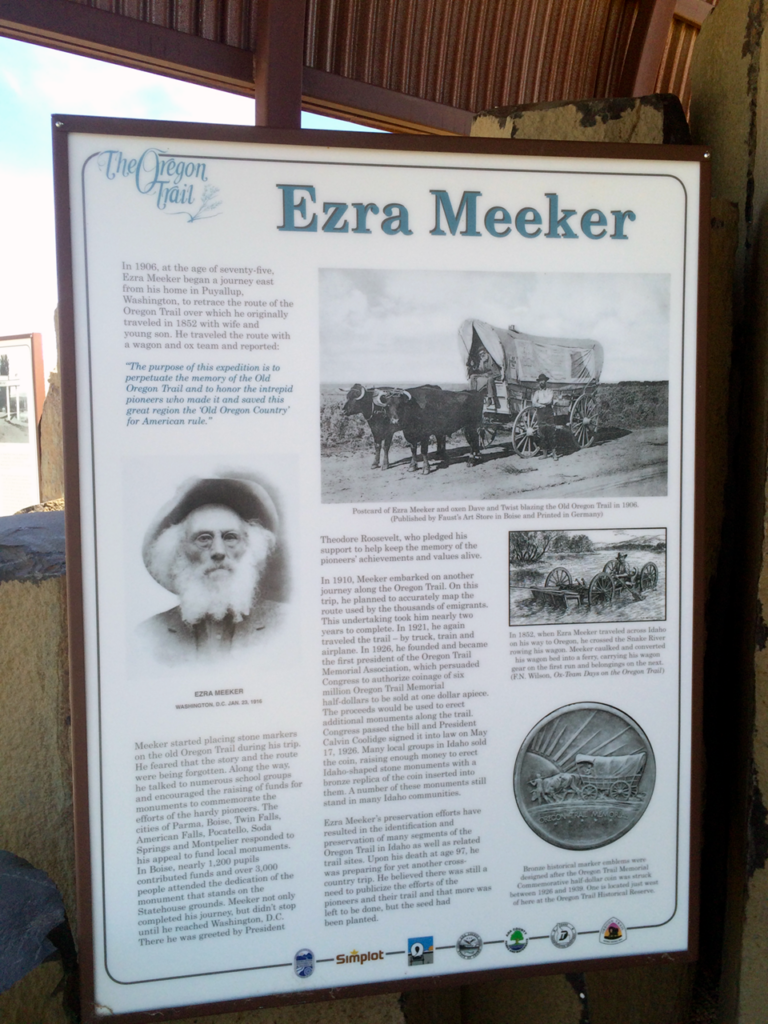

Even though I already mentioned that we don’t think that the back-to-the-land phenomenon in search of reconnection to pre-Industrial, seasonally managed time (see, for example, our recent visit to Mathieu Munsch in rural Eastern France), the United States has a unique story concerning settling the US West through individual and government converged interests, thanks to tales of starting afresh in some hypothetical, promised land (no matter how rugged and badland-grade), and measures like the 1862 Homestead Act, which tried to rein in a process that had started decades ago.

The first Homestead Act, signed by Abraham Lincoln, was an attempt to keep the country together, one year after the South had seceded from the Union. A previous Homestead Act (1860) had been passed in Congress but vetoed by President James Buchanan (Democrat). Lincoln’s long-term idea wasn’t far from previous idealist conceptions of the new country, like that of Thomas Jefferson, who, unlike Hamilton, thought Americans would flourish in landscapes of agrarian, well-tended semi-urban homesteads capable of providing self-sustenance, rather than big urban ensembles sustaining centralized industries.

But Lincoln’s promotion of the first Homestead Act was also the display of a fundamental difference with Southerners, who wanted to divide the West into big tracts and use slave labor to exploit them, as in Southern plantations. Lincoln saw it as an opportunity to expand the country to the Frontier and bring prosperity, allowing individuals and families (including immigrants applying for citizenship) to operate their own farms.

What was the US government encouraging when Walt Whitman wrote Pioneers! O Pioneers! in 1865, claiming the dynamic hymn in which many Americans identified themselves early on?

COME, my tan-faced children,

Walt Whitman, Pioneers! O Pioneers! (1), from Leaves of Grass, 1855

Follow well in order, get your weapons ready;

Have you your pistols? have you your sharp edged axes?

Pioneers! O pioneers!

Many Easterners and people from the old towns in the Midwest had settled into a new domestic life, often more prosperous than in Europe a few generations back, to the point that European visitors soon noticed that Americans seemed taller and better fed than their European counterparts. Regarding their character, Whitman says:

O to die advancing on!

Walt Whitman, Pioneers! O Pioneers! (14), from Leaves of Grass, 1855

Are there some of us to droop and die? has the hour come?

Then upon the march we fittest die, soon and sure the gap is fill’d,

Pioneers! O pioneers!

An outsider observes the Frontier (and predicts a country)

Also, European visitors saw as early as the early nineteenth century that Americans didn’t distinguish between classes, and there wasn’t a pejorative term equivalent to the European “peasant,” a passive and subjugated part of the population since the Middle Ages, who would, in part, feed the proletariat during the Industrial Revolution. Americans were fond of movement and reinvention, and urbanites—no matter their education or wealth—weren’t afraid of clearing land, building, advancing.

“The Americans never use the word “peasant,” because they have no idea of the peculiar class which that term denotes; the ignorance of more remote ages, the simplicity of rural life, and the rusticity of the villager have not been preserved amongst them; and they are alike unacquainted with the virtues, the vices, the coarse habits, and the simple graces of an early stage of civilization.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1st volume (1835); chapter XVII: Principal Causes Maintaining The Democratic Republic—Part III

Despite descending from an established old New York family, young Teddy Roosevelt’s entry into adulthood was marked by his experience settling in the badlands between the Dakotas and eastern Montana. He tried to raise cattle there, an area we’ve traversed a couple of times, as beautiful as it is raw, arid, uneven, and indomitable. To learn more about his experience there, and about the seductive character of the French nobleman who settled near him to raise cattle as well, the Marquis of Morès (Antoine de Vallombrosa), Edmund Morris’ first book of his biography of Roosevelt, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, is a book that won’t fail you.

“In the United States as soon as a man has acquired some education and pecuniary resources, he either endeavors to get rich by commerce or industry, or he buys land in the bush and turns pioneer. All that he asks of the State is not to be disturbed in his toil, and to be secure of his earnings. Amongst the greater part of European nations, when a man begins to feel his strength and to extend his desires, the first thing that occurs to him is to get some public employment. These opposite effects, originating in the same cause, deserve our passing notice.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd volume (1840); chapter XX: The Trade Of Place-Hunting In Certain Democratic Countries

Rushing forward

As we kept traveling across the US to produce all sorts of stories, I began to wonder: Who were those early Americans and migrants settling out West? What were their hopes and goals, and what did observers of the time say about the lives they left behind, their new lives out West, their aspect, and that of their new homes, compared to those of the Thirteen Colonies (and later the US West of the Mississippi) and Europe?

In our trips, as one insider-outsider observer like Tocqueville myself (minus the importance and, possibly, intellect), I’ve observed many of these realities on my own, for we’ve never traveled to places in search of the comfort of convenience and self-isolating tourist traps where one finds the same people that is trying to leave behind for a brief period of time. Quite the contrary: at this point, we’re experts in off-road and unincorporated areas.

I also found similar points of view and descriptions of what I’ve experienced myself in books written many decades ago, from Steinbeck’s 1962 Travels with Charley: In Search of America—which I have in much higher esteem than some critics, for what I’ve read after I finished it—to William Least Heat-Moon’s 1978 Blue Highways, an even more engaging travelogue around America’s back roads: A Journey into America. But, amid all accounts of the early homesteads, I’ve come to appreciate the little notes dispersed in Tocqueville’s (a count, member of a family massacred during the French Revolution, but rather a progressive and independent thinker for his time, French diplomat, political philosopher, and historian) 1835 Democracy in America.

Tocqueville’s first-hand descriptions and accounts still feel very suggestive and incisive today. Of course, he was a person of stature in his time, and his perception of Europeans as occupying a higher hierarchy than other races in the Western Hemisphere hasn’t aged as well as the rest of the book. Though Tocqueville’s blind spots are visible to us now, but his insight into the frontier temperament remains remarkably sharp.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s visit to the then-moving American Frontier precedes the first Homestead Act by almost three decades, yet he describes what the Homestead Act would rule after as law:

Many people dealt with desert, dust-bowl-prone, hardpan, rocky badlands; many also dealt with entrenched conflicts with Native Americans and the dangers of wildlife they weren’t used to, from towering bears to packs of wolves, as director Alejandro González Iñárritu depicts in his 2015 American epic movie The Revenant, based on the Frontier experiences of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) in 1823.

“It is difficult to describe the rapacity with which the American rushes forward to secure the immense booty which fortune proffers to him. In the pursuit he fearlessly braves the arrow of the Indian and the distempers of the forest; he is unimpressed by the silence of the woods; the approach of beasts of prey does not disturb him; for he is goaded onwards by a passion more intense than the love of life. Before him lies a boundless continent, and he urges onwards as if time pressed, and he was afraid of finding no room for his exertions.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1st volume (1835); chapter XVII: Principal Causes Maintaining The Democratic Republic, Part I

Children of homesteaders

In any case, more than 93 million contemporary Americans (around 33%) descend from original homesteaders: individuals and families who settled out West during the multiple Homestead Acts, among them the ones of 1862, 1866, 1873, 1875 (Indian Homestead Act, after many treaties were not honored by pioneers or the Federal government), 1904, 1906, 1909, and 1916.

“The Constitution confers upon the Union the right of treating with foreign nations. The Indian tribes, which border upon the frontiers of the United States, had usually been regarded in this light. As long as these savages consented to retire before the civilized settlers, the federal right was not contested: but as soon as an Indian tribe attempted to fix its dwelling upon a given spot, the adjacent States claimed possession of the lands and the rights of sovereignty over the natives. The central Government soon recognized both these claims; and after it had concluded treaties with the Indians as independent nations, it gave them up as subjects to the legislative tyranny of the States.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd volume (1840); chapter XVIII: Future Condition Of Three Races—Part VIII

Under the Homestead Act of 1862, settlers needed to build a permanent dwelling on their 160-acre claim and work at least a portion of it within a specified timeframe, or risk losing it. But the expectations were doable with little resources: the house was expected to be 12×14 feet or bigger, which helped “prove up” the land and secure the title, after a five-year period.

The dwelling itself, which was often built from felled trees in forested areas but initially made of more humble materials. Many early homesteaders built log cabins and also sod homes (especially on the prairie, but also on the high desert). Both log homes and sod homes, sometimes semi-buried like Scandinavian humble backstugas and Native American buried dwellings.

Log cabins had dirt floors, plank doors, and greased paper windows. Many Americans know that Abraham Lincoln (6 feet 4 inches tall, 193 cm, as an adult) was born in a humble one-room log cabin on a 300-acre farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky. It roughly measured 16×18 feet and had a dirt floor, one door, and one window. It was inhabited by 4 people: Abraham, his parents Thomas and Nancy, and his sister Sarah.

Bible, axe, newspapers (probably an almanack as well)

Some homestead initial dwellings were also partially made of stone, brick, adobe, or whatever was at hand in remote, arid areas. Whatever the material, homestead dwellings had to be ready within six months of filing the claim, which incentivized settlers to begin their adventure as soon as they knew where to claim their new property.

Also, homesteads needed “proof of improvements”: after five years, once they could legally apply for the deed to permanently claim the land, homesteaders needed to prove that they had lived on the land, built their house, and cultivated a portion of the terrain regardless of its roughness or fertility.

There’s no proof that Lincoln, born in 1809, ever read his contemporary Tocqueville, but this could well have been the case, due to their similar remarks on key topics. If he didn’t, he would have liked what the Frenchman had to say about the people actively pushing and blurring the Frontier towards the direction of the epic sunsets over the Pacific Ocean.

“At the extreme borders of the Confederate States, upon the confines of society and of the wilderness, a population of bold adventurers have taken up their abode, who pierce the solitudes of the American woods, and seek a country there, in order to escape that poverty which awaited them in their native provinces. As soon as the pioneer arrives upon the spot which is to serve him for a retreat, he fells a few trees and builds a log house. Nothing can offer a more miserable aspect than these isolated dwellings.

“The traveller who approaches one of them towards nightfall, sees the flicker of the hearth-flame through the chinks in the walls; and at night, if the wind rises, he hears the roof of boughs shake to and fro in the midst of the great forest trees. Who would not suppose that this poor hut is the asylum of rudeness and ignorance? Yet no sort of comparison can be drawn between the pioneer and the dwelling which shelters him. Everything about him is primitive and unformed, but he is himself the result of the labor and the experience of eighteen centuries. He wears the dress, and he speaks the language of cities; he is acquainted with the past, curious of the future, and ready for argument upon the present; he is, in short, a highly civilized being, who consents, for a time, to inhabit the backwoods, and who penetrates into the wilds of the New World with the Bible, an axe, and a file of newspapers.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1st volume (1835); chapter XVII: Principal Causes Maintaining The Democratic Republic—Part III

Rising from the back country

Also, in the same chapter, he adds an interesting footnote that the aforementioned American traveloguers Steinbeck and Least Heat-Moon would have appreciated:

“I travelled along a portion of the frontier of the United States in a sort of cart which was termed the mail. We passed, day and night, with great rapidity along the roads which were scarcely marked out, through immense forests; when the gloom of the woods became impenetrable, the coachman lighted branches of fir, and we journeyed along by the light they cast. From time to time we came to a hut in the midst of the forest, which was a post-office. The mail dropped an enormous bundle of letters at the door of this isolated dwelling, and we pursued our way at full gallop, leaving the inhabitants of the neighboring log houses to send for their share of the treasure.”

Above all, people like Tocqueville saw one secret in the young country, its practicality, its zeal for applied sciences, and the dream of creating a radical democracy. Americans, however, were less interested in more abstract and speculative areas:

“In America the purely practical part of science is admirably understood, and careful attention is paid to the theoretical portion which is immediately requisite to application. On this head the Americans always display a clear, free, original, and inventive power of mind. But hardly anyone in the United States devotes himself to the essentially theoretical and abstract portion of human knowledge. In this respect the Americans carry to excess a tendency which is, I think, discernible, though in a less degree, amongst all democratic nations.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd volume (1840); chapter X: Why The Americans Are More Addicted To Practical Than To Theoretical Science, Book 2

Upon observing the energy and determination of homesteaders, who often carried with them the education of well-stocked schools from the East and Midwest, Tocqueville sensed that the time of the United States was approaching quickly, as it would become increasingly apparent at the end of the century and especially after the First World War.

Wisdom of Democracy in America’s “Appendix S”

The Frontier wasn’t antagonistic of science, especially practical science, and didn’t neglect the basic literary canons, either. Unlike the unmotivated, uncultured peasants of the Old World, homesteaders surprised Tocqueville several times:

“There is hardly a pioneer’s hut which does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare. I remember that I read the feudal play of Henry V for the first time in a loghouse.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd volume (1840); chapter XIII: Literary Characteristics Of Democratic Ages

But, if I had to recommend anyone where to start in Democracy in America, or which passage to read from it, I’d pick Appendix S, a mere page and a half (depending on the edition) in the Second Book.

“As night was coming on, we determined to ask the master of the log house for a lodging. At the sound of our footsteps, the children who were playing amongst the scattered branches sprang up and ran towards the house, as if they were frightened at the sight of man; whilst two large dogs, almost wild, with ears erect and outstretched nose, came growling out of their hut, to cover the retreat of their young masters. The pioneer himself made his appearance at the door of his dwelling; he looked at us with a rapid and inquisitive glance, made a sign to the dogs to go into the house, and set them the example, without betraying either curiosity or apprehension at our arrival.

“We entered the log house: the inside is quite unlike that of the cottages of the peasantry of Europe: it contains more than is superfluous, less than is necessary. A single window with a muslin blind; on a hearth of trodden clay an immense fire, which lights the whole structure; above the hearth a good rifle, a deer’s skin, and plumes of eagles’ feathers; on the right hand of the chimney a map of the United States, raised and shaken by the wind through the crannies in the wall; near the map, upon a shelf formed of a roughly hewn plank, a few volumes of books—a Bible, the six first books of Milton, and two of Shakespeare’s plays; along the wall, trunks instead of closets; in the center of the room a rude table, with legs of green wood, and with the bark still upon them, looking as if they grew out of the ground on which they stood; but on this table a tea-pot of British ware, silver spoons, cracked tea-cups, and some newspapers.

“The master of this dwelling has the strong angular features and lank limbs peculiar to the native of New England. It is evident that this man was not born in the solitude in which we have met with him: his physical constitution suffices to show that his earlier years were spent in the midst of civilized society, and that he belongs to that restless, calculating, and adventurous race of men, who do with the utmost coolness things only to be accounted for by the ardor of the passions, and who endure the life of savages for a time, in order to conquer and civilize the backwoods.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2nd volume (1840); excerpt from Appendix S

Perhaps, the Frontier was never just geography. It was especially a wager about how much of life you would author yourself. The renewed interest in homesteading (even if marginal/idealistic) is the return of that wager when many people feel their days are controlled by decisions they didn’t take.

Tocqueville observed pioneers keeping a Bible, an axe, and a file of newspapers at their humble cabins. As a contrast, today’s homesteader carries a chainsaw, solar panels, and a phone full of tutorials.

The tools have changed. The wager has not.