When examining the return of totalitarian symbolism in today’s politics, we have to only ask our teenage sons what messages are breaking through on their screens.

I entered college in Barcelona in the mid-nineties. I didn’t appreciate it then, but we did a good deal of semiotics (or the study of signs and symbols and their impact on culture). It was an essential aspect of contemporary culture right before things were going to speed up, thanks to memes.

Whether we’re conscious or not about it, we live in a world of memetics. Words, signs, corporate logos, clothes, or flags carry emotions and convey much more than we think. The study of signs, symbols, and their meaning gives anybody an analytical peek into phenomena that behave like signifiers.

We all knew that symbols were important, and pop idols (but also political movements, some of them radicals from both left and right) have used memetics as a way to convey belonging and trigger gregariousness.

What we didn’t know then is that they can shape the world we live in, sometimes radically.

A genealogy: black shirts to “Blackshirts”

If we need proof of it: “black shirts” carried meaning in Europe’s thirties, as did swastikas (until then associated with Eastern beliefs), and today, people are being sent to prisons in El Salvador due to the interpretation of some of their tattoos’ alleged symbology (to hell with due process and fundamental rights, they say), while many cheer the controversial move while wearing caps with a particular color and message on them.

It’s all semiotics, or semiotics blended with the internet, to be more precise: the most popular memes replicate and win, while few care about critical thinking and veracity.

Back in the boring nineties, when we thought that History had ended and the world was flat, semiotics focused on traditional systems of meaning that had been refined and exploited in the twentieth century by mass media, propaganda machines, the literary avant-garde, and pop culture in general. Nobody expected the return of Agitprop, let alone a mainstream comeback of pseudo-fascist thought and symbology. But here we are today.

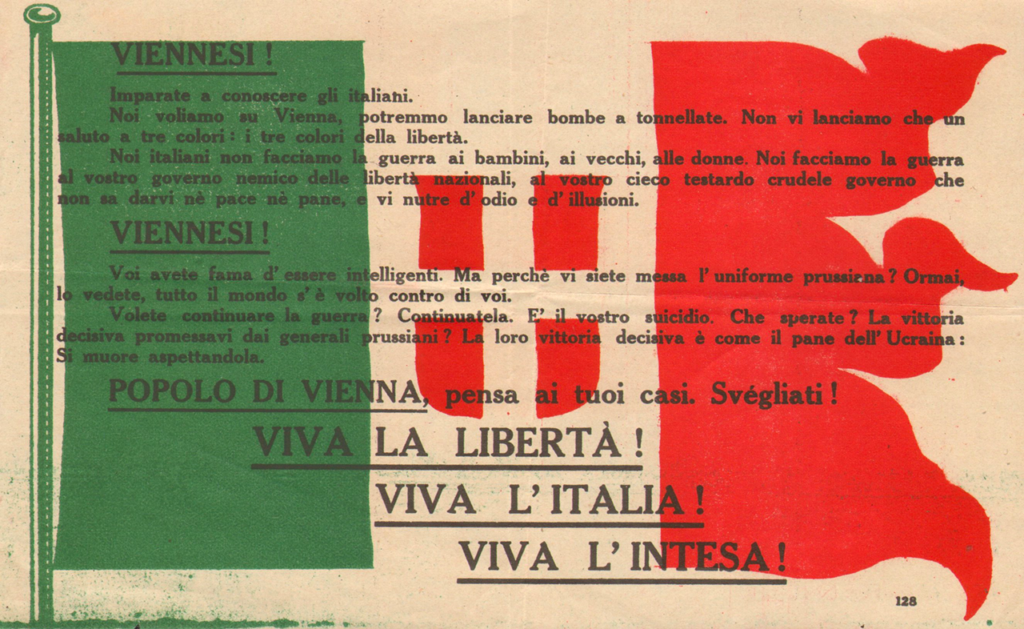

When I got to know semiotics for the first time, though, the discipline was an obscure topic in communication studies. In essence, little had changed between the flight over Vienna by Italian poet and nationalist Gabriele D’Annunzio—who, on August 9, 1918, dropped 50,000 propaganda leaflets over the enemy’s capital using proto-fascist flamboyance—and other symbolic acts that would drag the public to concerts at the end of the century.

In a decade since I entered college in 1995, however, mass media had changed forever, and social media promised anyone to become a contemporary D’Annunzio and deliver powerful Agitprop messages to the desired audience instantly, reaching people’s screens through the internet. No need to fly over their cities on a romantic Ansaldo SVA aircraft like the famous Italian agitator and future “Duce” of Fiume, the old Venetian city of the Adriatic (currently Croatia).

Umberto Eco’s disciples

I remember that one of our semiotics professors, a young assistant, had studied in Umberto Eco’s Dipartimento di Comunicazione at the University of Bologna. She wasn’t somebody capable of dragging attention or making the topic interesting, though I was quite impressed at her Umberto Eco connection—in the mid-nineties, Eco wasn’t only a writer of bestsellers but also the world’s biggest eminence of semiotic studies. I remember reading The Name of the Rose around that time and enjoying it very much.

Umberto Eco, the novelist and cultural critic, the old-school intellectual whose personal library at home would have made Borges proud, was a semiotician above all, a son of the traumas of twentieth-century Europe like the French essayist Roland Barthes, a fellow semiotician, master of the sign systems that defined Western popular culture.

Both Barthes and Eco grew up seeing how European fascism and communism encouraged art as propaganda and noticed early on the importance of communication to spread narratives capable of channeling the energy and frustrations of the masses.

In 1995, right when I entered college, Umberto Eco published Ur-Fascism (Eternal Fascism: Fourteen Ways of Looking at a Blackshirt), a short essay explaining the features that define any fascist movement: worship of tradition, rejection of modernism, fear of difference, appeal to a frustrated and scared middle class, and obsession with a plot.

A teen Italian fascist

Like Barthes, Eco grew up in a society where these signs sneaked in through culture before materializing in policy and power. He knew this firsthand as a gifted pro-Mussolini child growing up in northwest Piedmont.

“In 1942, at the age of ten, I received the First Provincial Award of Ludi Juveniles (a voluntary, compulsory competition for young Italian Fascists—that is, for every young Italian). I elaborated with rhetorical skill on the subject ‘Should we die for the glory of Mussolini and the immortal destiny of Italy?’ My answer was positive. I was a smart boy. I spent two of my early years among the SS, Fascists, Republicans, and partisans shooting at one another, and I learned how to dodge bullets. It was good exercise.”

Three years later, the same boy was excited to see how, in April 1945, the partisans took over Milan. Then, not much later, he saw the first American soldiers in his area:

“The first Yankee I met was a black man, Joseph, who introduced me to the marvels of Dick Tracy and Li’l Abner. His comic books were brightly colored and smelled good.”

To Eco, the American soldiers were the representation in the flesh of anti-fascism and anti-totalitarianism.

“In May we heard that the war was over. Peace gave me a curious sensation. I had been told that permanent warfare was the normal condition for a young Italian. In the following months I discovered that the Resistance was not only a local phenomenon but a European one. I learned new, exciting words like réseau, maquis, armée secrète, Rote Kapelle, Warsaw ghetto. I saw the first photographs of the Holocaust, thus understanding the meaning before knowing the word. I realized what we were liberated from.”

But, as he wrote in his 1995 little essay, there was the possibility, decades after totalitarian governments ruled over Europe using propaganda with effectiveness, that “another ghost” could still be stalking Europe (not to speak of other parts of the world).

When writing these lines, Umberto Eco was predicting our time of fragmentation and clash of narratives, one where propaganda has democratized and reactionary narratives turn out to beat democratic discourses in social media.

The liturgy of fascism and the disenfranchised

Italian fascism—Eco writes—became the symbol of a type of militantly anti-modern and nationalist totalitarianism, a synecdoche (a word to describe other similar movements):

“Italian fascism was the first right-wing dictatorship that took over a European country, and all similar movements later found a sort of archetype in Mussolini’s regime. Italian fascism was the first to establish a military liturgy, a folklore, even a way of dressing—far more influential, with its black shirts, than Armani, Benetton, or Versace would ever be. It was only in the Thirties that fascist movements appeared, with Mosley, in Great Britain, and in Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Yugoslavia, Spain, Portugal, Norway, and even in South America. It was Italian fascism that convinced many European liberal leaders that the new regime was carrying out interesting social reform, and that it was providing a mildly revolutionary alternative to the Communist threat.”

Thanks to books like Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, the enemies of liberty were associated with “fascism,” even if Robert Jordan is fighting against the local Spanish Falangists. Even FDR gave fascism the credit for being the origin of a (very modern) anti-modern antagonist of liberal democracies:

“The victory of the American people and their allies will be a victory against fascism and the dead hand of despotism it represents.”

Fascism was always weaker than Mussolini stated, although the Duce had learned a very valuable lesson from the “national poet” Gabriele d’Annunzio, a decadent dandy who understood the attractiveness of creating a cult of heroism and manliness to entice the disenfranchised youth: mass media could be used as “amplifiers of meaning,” for any symbolic action could be covered as a source of propaganda to influence the public.

A romantic nationalist dropping leaflets over Vienna

When D’Annunzio dropped 50,000 leaflets over Vienna in 1918 (Mussolini analyzed correctly), the real target wasn’t Vienna’s population—it was Italian and Allied public opinion. The pictures taken from the planes by the team assembled by D’Annunzio were sent to newspapers, which turned the flight into a viral event of its day (a kind of pre-meme meme: an act engineered to be spread, told, and retold).

Hence, Mussolini’s Blackshirt marches and rallies became the memes of their time in Italy’s 1920s and 1930s, inspiring Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies. Stage-designed by the architect Albert Speer, the Nuremberg event used the choreographed movements and symbology strength that we now associate only with the “sacred performance” of the Olympics opening ceremonies. But, instead of celebrating sports and the human spirit of personal performance, the precision and militarized discipline of totalitarian rallies blended mythical and nationalistic symbolism with power as a symbol of the nation’s strength.

It’s no coincidence that Leni Riefenstahl’s exquisite cinematography reached its apex in connection with the Olympic aesthetics, as shown on Olympia (1938), her film about the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Mass synchronization blurred the line between representation and ideology, and the visual language of fascism excited many people in a moment of transition and crisis of values like nothing else had done before. But the use of uncomfortably authoritarian aesthetics and visual languages isn’t a thing from the past: today’s fitness realm and trends like the “tradwife” fad are proof of the potential of more dangerous proposals and aesthetic techniques already proven by the anti-modern mass movements of the 1930s.

Gabriele D’Annunzio and his fin de siècle decadence were ahead of their time; one century after D’Annunzio’s influence over Mussolini and fascism, his radical methods of communication were a precursor not only of fascist propaganda but of the media fragmentation and siloed radicalization of today. When flying over Vienna, D’Annunzio didn’t drop bombs—he dropped poetry. The act had no tactical value, only narrative value, like a postmodern message where the move replaces action with simulation, just like Jean Baudrillard would theorize decades after in Simulacra and Simulation, the book shown in Neo’s room in The Matrix.

Umberto Eco would tell us that in semiotics, the medium (airplanes, television, social media) becomes the message. Or rather, the battlefield, as anyone can feel when connecting to X and navigating through the “For You” tab, a true tool of Agitprop at the service of the platform’s owner that would make Filippo Tommaso Marinetti—another precursor of fascism and father of the Futurist movement—proud.

The theatrical side of fascism, its bombastic reliance on a performative sense of collective belonging capable of making insecure people feel that they finally have found a purpose bigger than themselves, is the side of the semiotics of totalitarianism that screams for attention. But fascism also attracted capable, moderate—yet ambitious—people, technocrats who opted in despite quickly spotting the excesses and contradictions.

When personal ambition trumps moral compass

Also in the mid-nineties, I read Albert Speer’s autobiography and was quite fascinated by the experience. How a seemingly reasonable, well-educated young man who had some ambition in his time and country became one of the 24 “major war criminals” charged by the International Military Tribunal for Nazi atrocities, was a transformation worth reading. I became instantly engaged and recommend it, especially now.

When reading Speer, I remember thinking something for the first time, something so disturbing that I couldn’t get over it for a while. Perhaps because, back then, I was reading about the inner workings of communication and propaganda in college, and I was becoming increasingly conscious of how manipulable we all can be—even the best educated and informed, just like Speer. My thought then: living in Speer’s world in Germany’s early thirties, which side would I have been on? Was I sure I would have spotted the risk that Nazism represented or decided to minimize the subsequent “anomalies” that ultimately led to atrocities? Would I have called out the injustices and attacks on the population without due process? How about Kristallnacht? How was it possible that it all had happened, and people like Albert Speer had gone with it?

Not that Albert Speer lacked a moral compass or didn’t see the contradictions of some of the thugs surrounding the Nazi core: he did see the dilettantism, the batshit-crazy proposals, the abuses, cringe behavior, and tacky taste of people like the eccentric morphine addict Hermann Göring. He also fell for the spell of Adolf Hitler and his grand plans to make Berlin an eternal capital, with pastiche buildings rivaling those of Ancient Greece or Rome, which he could make a reality as the architect of the regime.

Studying his reaction to the mass demonstrations, their symbology, and their effect on people, Albert Speer thought it was worth taking the ride with a regime that was set to disassemble the Weimar Republic to create the Third Reich. He ended up being Minister of Armament and War Production in World War II, a mere puppet of the Führer, which he had admired for his charisma but ended up despising. I wouldn’t define Speer as a fanatic—or not more of a fanatic than many people in today’s first line of politics.

It can totally happen here, there, anywhere

When thinking about Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, which I see widely quoted nowadays, I can’t help but think that fascism could, in fact, rise in our time with impressive speed, given the overall, shallow lack of depth and values of many people I encounter. If anyone wants any proof that they themselves could, in fact, become a militant part of a fascist regime, there’s no better read than Albert Speer’s autobiography.

Umberto Eco’s analysis of fascism coincides with that of Hannah Arendt. Totalitarianism often arises not through brute force (say, like Franco’s Spain) but through gradual erosion of truth and institutions (emerging from parties and leaders who win democratic elections). In this process, semiotics plays a key role, especially when it’s time to dismantle institutions. Fear and confusion do the rest.

Somebody recommended to me recently a brief book published in France in 2017 that I didn’t notice when living there, even though Éric Vuillard won the 2017 Prix Goncourt (France’s most prestigious literary prize) with it, so I brought it with me on a recent trip and read it on the plane. L’Ordre du jour (The Order of the Day) is a small book that can have a big impact due to its poetic undertones and haunting content.

Through a series of vignettes, the book shows how, behind the big messages and pompous mobilizations, Nazism triumphed only due to the cowardice of many powerful people who sacrificed their moral compass for the promise of benefiting from a regime that they despised in private. Backroom deals, passive complicity, and bureaucratic banality helped usher the Nazi regime’s dominance of German society.

The first vignette echoes today’s world: it’s the February 20, 1933, secret meeting of German industrialists with Hermann Göring and Adolf Hitler at Reichstag President’s Palace, Berlin. On it, a group of magnates of the time—including the representatives of Siemens, Bayer, Opel, IG Farben (a giant conglomerate later split by the Allies to prevent its world domination), and many others, attend (as “avatars” of the companies they represent) and agree to financially support Hitler’s Nazi Party in exchange for promises of stability and purge of communist unions.

The Order of the Day

As I was reading this first vignette, I couldn’t help but see a recent picture of magnates assembling to bow to power—and willing to go as far as needed, as long as their companies’ interests advance in the new regime.

I wonder about the semiotics of such a vignette.

“A wave of approbation swept over the seats. At that moment, there was a sound of doors, and the new chancellor finally entered the room. Those who had never met him were curious to see him in person. Hitler was smiling, relaxed, not at all as they had imagined: affable, yes, even friendly, much friendlier than they would have thought. For everyone present, he had a word of thanks, a dynamic handshake. Once the introductions had been made, everyone again took their comfortable chairs. Krupp was in the first row, picking at his tiny mustache with a nervous finger. Right behind him, two directors of IG Farben, along with von Finck, Quandt, and some others, sagely crossed their legs. There was a cavernous cough. The cap of a pen produced a minuscule clink. Silence.

“They listened. The basic idea was this: they had to put an end to a weak regime, ward off the Communist menace, eliminate trade unions, and allow every entrepreneur to be the führer of his own shop. The speech lasted half an hour. When Hitler had finished, Gustav stood up, took a step forward, and, on behalf of all those present, thanked him for having finally clarified the political situation. The chancellor made a quick lap around the table on his way out. They congratulated him courteously. The old industrialists seemed relieved. Once he had departed, Goering took the floor, energetically reformulating several ideas, then returned to the March 5 elections. This was a unique opportunity to break out of the impasse they were in. But to mount a successful campaign, they needed money; the Nazi Party didn’t have a blessed cent and Election Day was fast approaching. At that moment, Hjalmar Schacht rose to his feet, smiled at the assembly, and called out, ‘And now, gentlemen, time to pony up!’”

The other vignettes show, among other things, the British and French attempted appeasement of Hitler, depicting the cowardice of figures such as Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax, key figures in British foreign policy during the 1930s (whose character contrasts with that of Winston Churchill).

There’s also room for the behind-the-scenes depiction of the Anschluss (Germany’s annexation of Austria). I couldn’t help but read the pages thinking about a frivolous kind of meme-expansionism that is taking over today’s semiotics.

Vuillard seems to acknowledge that History is often shaped by banal decisions, opportunism, and the failure to resist. His little book dismantles the myth of inevitability around fascism’s rise, showing that many collaborated, directly and indirectly, to benefit from a new era, sacrificing real patriotism and embracing fake nationalism in the process.

If and when the moment arrives, how many decent people will choose to emulate Albert Speer instead of calling foul?

Meanwhile, the world of semiotics shows how symbols, signs, and social media manipulation shape political narratives and influence public perception, one manosphere podcast at a time. In the world we live in, any moderate proposal will need to understand how to appeal to people using the same tools that have catapulted the engineers of chaos to power.