September 2022 refuses to be a dull back-to-school month, what the French call the “rentrée.” But in the last week of September, a quote by Lening comes to mind, as we feel that the news cycle insists on remaining too crowded with essential events: “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.”

The sense of instability is real, but the apparent chaos is transitory, mainly driven, according to analysts, by the passage from an economic model of unfettered globalization that failed to deliver prosperity to the middle classes in developed nations, to a post-global reality that tries to keep real production value as close to citizens (consumers, voters) as possible. In this context, a widely-known quote by Antonio Gramsci seems more relevant than ever:

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

The actual quote, written in 1930 in his Prison Notebooks, is:

“The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

In systems theory, science, economy, or art, philosophical emergence refers to an entity that contains more meaning than the simple addition of its parts since some complex properties or behaviors “emerge” only when the elements combine as a whole. For example, beehives and anthills are entities with more “meaning” and coordinated capabilities than the combination of bees or ants. In the economy, individual actions create the “emergence” of phenomena carrying more complexity than anticipated.

This is happening right now at an unprecedented scale in interconnected human societies. In the economy, Central Banks across the world are raising their rates to slow growth and dampen spending. But such coordinated action could trigger unwanted consequences, argues The Economist.

Weeks that contain decades

The zeitgeist insists on bringing it all at once and such weeks where decades happen arrive too often clustered upon each other. Or so it’s the subjective feeling we have when we see the interrelation between what happens at a macro scale and the effect of such events in our lives as if reality were reminding us of chaos theory. Sometimes, the butterfly effect seems less incredibly rare than the ripple effects we see unfolding, no matter where we are.

It’s been another bumpy week for stocks, currency fluctuation, disturbing political shockers, extreme weather events, and an array of war-related news that somehow affect what we experience around us: supply chain issues will determine how long we wait for a product delivery, a new appliance, or a car, whereas measures to counter inflation also take a toll while remaining useless for consumers in the short term.

Giorgia Meloni’s election win in the 2022 Italian general election is a reminder of how general discontent can materialize into political action in the age of social media, especially in a country that saw the rise of web-based, “anti-establishment” political activism (or, as Paris-based Italian writer and geopolitics expert Giuliano da Empoli has explained, Italy can be seen as “the Silicon Valley of populism” thanks to Gianroberto Casaleggio, Beppe Grillo, or Silvio Berlusconi).

But Giorgia Meloni’s victory in Italy concerns less European Union’s main chancelleries than the act of sabotage that appears to have “permanently damaged” the Nordstream 1 and Nordstream 2 pipelines connecting Russian oil to Germany under the Baltic Sea: the pressure collapse in both infrastructures bulldozes the umbilical cord that kept Germany’s interests open to eventually reinstate agreements with Russia once the war was over. With no carrot dangling in front of German realpolitik, European energy will need to evolve even faster than thought.

Back when the paternalizing focused on PIGS

A New York Times graphic displaying the rather spectacular shoot-up of German inflation, currently at 10.9%, represents a shock to German economic orthodoxy. To a country that associates the rise of Nazism to the effects of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic, the current rate not only hits a 70-year high but resonates in the country’s psyche. The concerns about high energy and food prices have prompted German Chancellor Olaf Scholz to declare that “the German will do everything so that prices sink.”

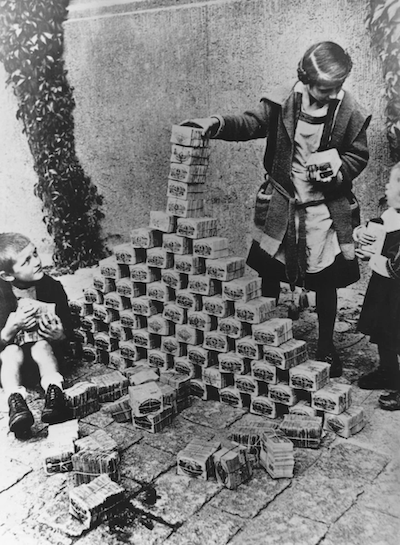

Hyperinflation reached levels so absurd in Weimar Germany during the ’20s that children used worthless banknotes as cheap toys to build castles with, so seeing the Eurozone’s overall inflation reaching over 10% in September brings back as many bad memories and reminiscences of early-twentieth-century tensions as the war in Ukraine.

The European Central Bank has long advocated for policies that harmonize inflation and relative debt among its members so the shared currency and interest rates wouldn’t exacerbate imbalances, or so this strict orthodoxy —backed by Germany and its immediate Central and Northern European neighbors— claimed.

The Eurozone’s memory also goes back to the early 2010s tensions among its members: when the US subprime crisis exploded, soon evolving into a debt crisis among the weakest Western European economies (often dismissed by British and US financial press and commentary as PIIGGS, then merely PIGS as Ireland leveraged its international exposure to the financial turmoil: Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain), German refusal to back a common European mechanism to refinance sovereign debt exacerbated economic issues and translated into a painful economic reality for citizens in countries waiting for economic rescue. Those were the days when the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal hosted paternalizing articles, Michael Lewis wrote compelling articles on the disarray of de European sovereign debt crisis, and “Grexit” was the buzzword.

In the early 2010s, populism was on the rise in the region, and op-ed articles published by the NYT back then contrasted the relatively quick recovery of the US economy (mainly through devaluation and by lowering interest rates) with the UE’s stubbornly austere plan to trade rescue packages with troubled countries in exchange of painful measures imposed upon the population. The austerity plan imposed by a German-influenced European Central Bank persevered in keeping inflation under control.

Dragging Draghi, then and now

The Eurozone was in technical deflation when the then ECB President, Mario Draghi, ended with speculation against several eurozone countries by simply stating in 2012 that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to preserve the single currency. Shortly after, monetary transactions within the euro would ease the financing pains of the most exposed countries. Grexit wouldn’t finally catch as a buzzword, but Brexit did months before Donald Trump won the US election in November 2016. Draghi would eventually leave the ECB, and end up becoming the “grown up” Italian Prime Minister that could now be followed by Meloni. It all reads like a book Giuliano da Empoli could easily put together.

Vladimir Putin also wanted a part of this week’s news cycle, announcing the Russian annexation of Ukrainian regions in defiance of international law, “four new regions” that add up to Crimea’s annexation in 2014. Some nervous analysts want to draw parallelisms with Hitler’s annexations in Central Europe before the war —and the West’s connivance to try to come to terms with the German dictator.

Winter is coming, and Vladimir Putin will use European energy needs as a geopolitical weapon, though critical voices within the army and in Russian public opinion, especially after he announces a “partial mobilization” of 300,000 reservists and its visible effects.

Moving truck parked by 10 Downing Street

Also this week: Great Britain refuses to leave the collective high emotional pitch that captured world attention after the Queen’s death: the collapse of Boris Johnson’s government wasn’t supposed to take down the conservative Administration, but Liz Truss has managed to further complicate the country’s institutional and political crisis in record time.

And, like Olaf Scholz’s declarations about Germany’s inflation, the Bank of England intervened on Wednesday to try to calm markets and attenuate the rise of borrowing costs, confirming that it will buy long-dated treasury bonds in “whatever scale is necessary to effect the outcome.”

Truss’s announcement of a fiscal overhaul has been dubbed “fairy tale” economics for a reason, and the tax cuts announcement have earned the biggest devaluation of the pound against the dollar since 1985. The fiscal measure has prompted the IMF to warn the UK of “inequality risks.” Investors ditched British treasure bonds due to the comically bad timing of the biggest tax cut in half a century, right when inflation and anemic overall growth of the economy would have demanded caution and a projected image of having things under control.

In one week, the Bank of England raised interest rates by half a percentage to tackle inflation; less than 24 hours later, the government announced the tax cuts. Britain’s credibility with investors seems to put the country in the position experienced by the Eurozone countries that struggled during the sovereign debt crisis, and the pound, an institution of a currency, is now subject to memes in which its volatility is compared to that of “shitcoins” (if only to feed the fintech meme machine).

The macro absurdity hurts citizens

As in the butterfly effect, apparently abstract and inconsequential definitions of a momentary perception in “the markets,” such as the “loss of credibility with investors,” leads right away to consequences in real life. As the pound crashed this week in the markets and the UK Treasure quickly tried to calm the panic, British bond prices collapsed and borrowing costs soared, which in turn affected the mortgage market and weakened the perception of pension funds’ solvency.

But the week resisted to finish without the scare of another cyclical reminder in the zeitgeist we happen to go through: the damage of hurricane Ian, the second major storm in the current Atlantic hurricane season, becoming a Category 4 hurricane on September 28 as it entered the west coast of Florida and flattened entire coastal communities.

Yet, despite the apparent weakness of things we considered as sound and boring as the presence of Queen Elizabeth II in the foreground of a world that had left world wars, colonialism, and European dominance for the era of the Cold War and, finally, the Pax Americana, there’s a strong case for meliorism if we analyze world progress in aggregate, argue —among others- Max Roser, German economist at Oxford University and founder of data research website Our World in Data.

Things may look messy when instability occurs at the core of the international order issued from World War II, not yet fully substituted in the realms of economic and cultural soft power. Yet some countries have a long and painful relationship with institutional and economic instability —and the loss of international credibility derived from it—.

Lessons from hyperinflation champions

The BBC dedicates two recent episodes to showcase how people deal with currency collapse and chronic hyperinflation and how it affects their lives: Money in Lebanon, and Argentina: Life with hyperinflation.

I remember reading a may 2019 article by Argentinian writer Martín Caparrós, a colorful depiction of the quotidian struggle that the citizens of Buenos Aires endure just to get by. The “Paris of Latin America” and the country with the eternal, spoiled potential of becoming a model society.

The article, published in El País, vividly describes how people in Argentina —once a rich country attracting Europeans in search of a better life— cope with a decades-long fatalism derived from economic stagnation, political instability, and the first-hand, everyday consequences suffered by citizens. When the macro scale visibly trickles down into everyday life, it becomes real for people. But hardly ever those taking the biggest toll during moments of hardship are given the tools to understand causes and effects, reinforcing the case for populism —and of long-term turmoil.

I shared the article with one Argentinian friend —one of those who, despite being able to leave the country due to his recent European roots, has decided to stay. He finished the email he wrote back like this (translated from Spanish from an email sent on May 28, 2019):

“What Caparrós raises is the eternal Argentine paradox (another of many), that of a country with the necessary resources to guarantee a good life for the majority of its inhabitants, but in which one of every two children is poor. I guess it’s not for nothing that something as melancholic as tango is from Buenos Aires.

“Concerning this, I like to listen to Mujica, the former Uruguayan president, who invites us to live a sober life in which the most important thing should be ‘freedom,’ understood as having time to do what we like: to have time to relations, to cultivate oneself, and fulfilling dreams. He believes that the things we buy are paid for with the time of our lives, a time that is limited and slips away easily. That today’s consumerism has prevailed and has developed very powerful tools of persuasion (…)”

Update

As a consequence of this article, the old conversation was revived, and Germán thought it necessary to make a minor update:

“More than three years passed [since the previously mentioned email interchange on Argentina], and the country’s situation has aggravated to the point that, for many Argentines, there’s no consolation in Mujica’s ideas of sobriety and common sense. The country’s status is unfortunate: every day, there are more people who, despite having a job —and having forcibly renounced to unessential indulgences— do not manage to cover basic needs and are statistically considered “poor.”

“On the other hand, it’s shocking to see how the country’s economic struggles are internationally perceived as hyperinflationary. The fact is: inflation is so entrenched in the country’s reality that we are reluctant to concede that it is an issue as critical as we’re told (for us, to speak of hyperinflation is to have monthly rates of 764%, as it happened in 1989. Annual variations of 10% do not represent a cause for alarm). But when world inflation is added to endemic structural inflation, the picture is not at all encouraging… It is estimated that by the end of the year, accumulated inflation will be close to 100%, and there is little confidence that it can be effectively controlled.”

Moderation and introspection on everyday morality help a lot, in my friend’s opinion. There are things we can control, whereas other phenomena are out of reach, and all we can do is adopt an instructed perspective of macro situations. Some things seem to be in the hands of the gods, and some in the hands of mortals; my friend finishes with a somehow fatalistic note, eluding the “Render unto Caesar” from the synoptic gospels and preferring Homer instead:

“Go thou within, and let thy heart fear nothing; for a bold man is better in all things, though he be a stranger from another land.” Odyssey, Book VII.