Some monuments were never meant to be inhabited. Yet in 19th-century Paris, a child lived inside the hollow body of one. The afterlife of ambition often begins on the inside.

We hardly start things from scratch. For good and bad, we sometimes stand on the shoulders of gentle giants, or on those of mischievous midgets. No matter how withdrawn from society we want to be, we are participants in our time and condemned to be free: we aren’t passive subjects if we choose to be, and we have more agency over our lives than we sometimes want to acknowledge.

In 1946, the core of Europe felt exhausted, morally and physically defeated after the horrors of the war. In Paris, using the cafés’ heat to warm himself enough to write more comfortably, Jean-Paul Sartre answered those who saw in existentialism a form of nihilism, deflecting their shared responsibility for the atrocities.

People, he said, weren’t only condemned to be free; they could choose their actions, no matter their limitations or personal circumstances. People were responsible for overcoming passivity and living their lives accordingly, but for many, the burden was so great that it created all manner of imbalances.

Perhaps influenced by the news, I’m reminded today of this short text by Sartre, as I see how many people seek justifications for their likes by scrolling on their phones rather than pausing to think for themselves. By seeking justification on our screens for anything happening to us or around us, we might find a false comfort in excluding ourselves from the events. In the long run, there’s nothing to be won from digital tools tailored to keep us numb and free of any responsibility.

Escapist topics to see things with perspective

Sartre’s text was conceived not far from the place we used to live in Paris many decades later; he was writing at the beginning of the order created after World War II, and we looked at the same streets while the same order, which many called Pax Americana, was falling apart before our eyes. In 1946, as seventy-five years later (when we endured the demonstrations by the Gilets Jaunes in rainy mornings and needed to bike with our daughter across the city center to make sure she made it safely to school), Paris looked like a Marc Chagall painting: fractured yet luminous, suspended between collapse and possibility, where disparate viewpoints coexist in a single frame, and where history, intimacy, and uncertainty float together without resolving into a single, reassuring perspective.

And, sometimes, in 1946 and also during Covid, people walked the street like a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti: elongated and solitary, reduced to fragile silhouettes moving through an emptied city, advancing despite exhaustion, uncertainty, and fear—figures stripped of ornament and illusion, defined not by what they possessed or proclaimed, but by the simple, stubborn act of continuing forward, one step at a time.

It was back then, years ago, months before the world learned of a virus spreading rapidly in the Chinese province of Wuhan, that Kirsten was featured in an article about YouTube creators in Vanity Fair. It was, I believe, the November issue, with Joaquin Phoenix on its cover.

Back then, Paris was our city, even if we mostly kept to ourselves as we’ve always done since we started the site and the channel. It all now feels remote, especially when I notice how much older and more mature our kids are, and how easily they blended into their California peers, showing not a hint of their previous lives abroad.

A video about the psychogeography of Paris through books and authors

It may not have been related to this fact, but a few weeks after Vanity Fair published a photograph of our family along with a positive review of Kirsten’s channel content and style, someone at YouTube contacted her and offered her the opportunity to create a video sponsored by Alphabet. As on a few other occasions, we declined the offer due to our chronic lack of time and unease about the growing merger of consumer culture and life. So, Kirsten politely refused the offer.

A couple of weeks later, the same YouTube manager insisted they wouldn’t control the video in any way and that we’d be paid regardless of the piece’s performance. In other words, we could aim to create a niche piece we liked, as long as it mentioned one of Google’s products (we chose Google Maps). So we accepted the generous one-time offer and decided to dedicate the video to the city that had hosted our family for years.

Knowing that a video assembled as a collage (a very Parisian format, used by children at schools, and also established artists since its inception as a fine art technique in the city around 1910-1912, via Cubist pioneers Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso) would lack the focus of conventional Kirsten’s pieces, we knew the video would likely have limited reach.

We imagined the piece as a one-day Odyssey through the city, much as Stephen Dedalus wanders Dublin on June 16, 1904, in James Joyce’s Ulysses, the famously difficult modernist novel published (and written) in Paris years later, when the Irish author blended with the young foreign writers that Gertrude Stein dubbed the Lost Generation. We imagined our quotidian Odyssey as a bike tour using Paris’ shared bikes, Vélib, to encounter the places where several writers had lived and conceived their stories, inspired by Guy Debord’s concept of psychogeography, or the study of the effects on us of the experience of others in a given geographical environment.

For example, many people have never been to New York City or to Paris, but many references from pop culture, accounts from others, stories read, etc., make them, in a way, cultural inhabitants of such places, for they have experienced them through songs, movies, stories explained by relatives who lived there or visited such places. From our perspective on Paris, we decided to show others what it feels like to take a bike ride to places where book characters lived, the apartments where authors lived, the places where they gathered, etcetera.

Balzac’s mischievous regard

No wonder the video wasn’t a blast. Also, as soon as watchers saw Kirsten talking about Google Maps in the middle of the video, the video stalled even more, and we didn’t bother to ‘optimize’ the piece’s title or its thumbnail, which was simply a selfie of Kirsten and me standing before Rodin’s statue of French writer Honoré de Balzac at the intersection of Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard du Montparnasse. The video’s title: “In search of lost books: an odyssey across Paris.”

As it happens with the psychogeography of places, our experience in the City of Light might feel skewed or limited to others, but, as Sartre recommended in his 1946 article on the nature of existentialism, we gave it our best shot and tried to act with the agency we’ve been given, as people living our times. And, who knows, perhaps our epoch feels with false confidence that we are past books and now it’s all visual culture, the shorter and snappier the better. It all feels a bit of a blend of Orwell’s 1984 vibes and Huxley’s Brave New World soma fix for the cortex. And that’s why Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 film Strange Days made such an impact on me in college, when I couldn’t stand my own cynicism about the world.

Interestingly, the movie was a commercial flop so big that it nearly derailed Bigelow’s career (go figure). In the movie, substance addiction has morphed into digital media addiction via the SQUID device, a fleshy, MiniDisc-type device that people put atop their cortex, allowing users to record and replay lived experience directly through the nervous system, which the protagonist (played by Ralph Fiennes) abuses.

Our intention with our little video wasn’t to numb people’s brains with our lived experience, but consciously invite them to a bike ride, a life-in-a-day type of video, at a moment when people had a hard time traveling. We thought positive escapism might have a small, positive impact on our viewers.

The fascinating story of the Elephant of the Bastille

Among the many places we showed, there was one that wasn’t there in the flesh, but had existed: we biked to the Place de la Bastille, a place with special significance in the city, for the Revolution started there, where the infamous prison once stood until the storming by the population and subsequent physical destruction in 1789-1790, a year that turned the place into an open scar.

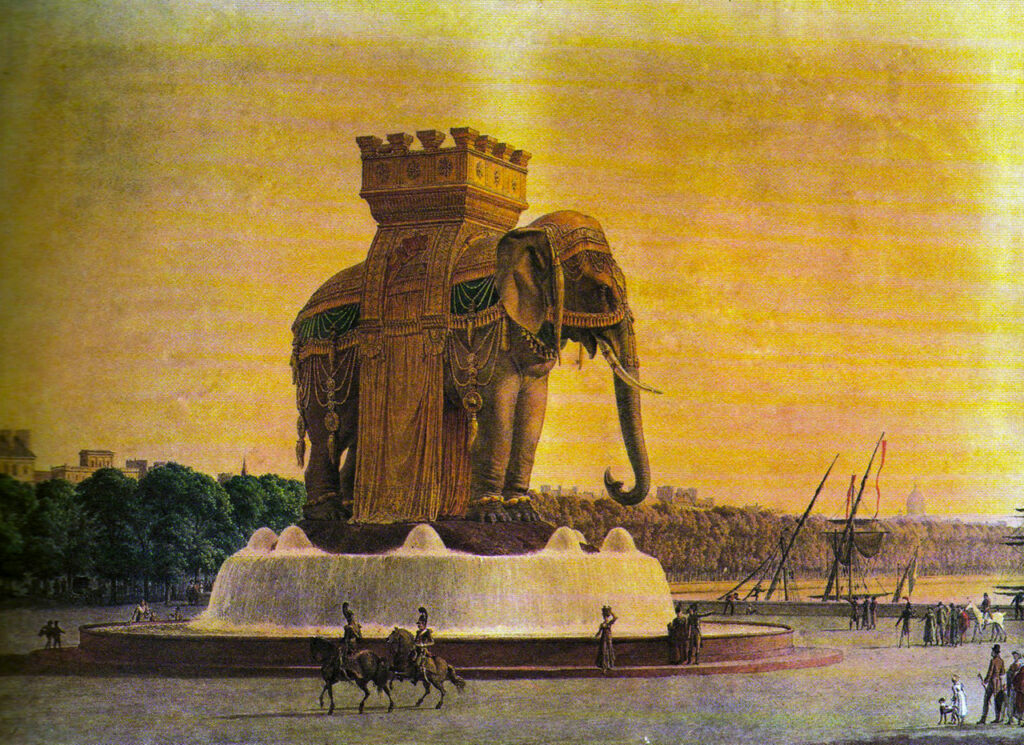

But we didn’t bike there to talk about the disappeared prison in our video. As psychogeography reminds us, personal and collective events, real and imaginary, often crowd a place like geological strata, and the Place de la Bastille, which still feels cold and detached from the city in many ways, is one such place. Instead, our view of the square wanted to pay homage to a failed project by Napoleon I, who planned a giant elephant fountain right in the middle.

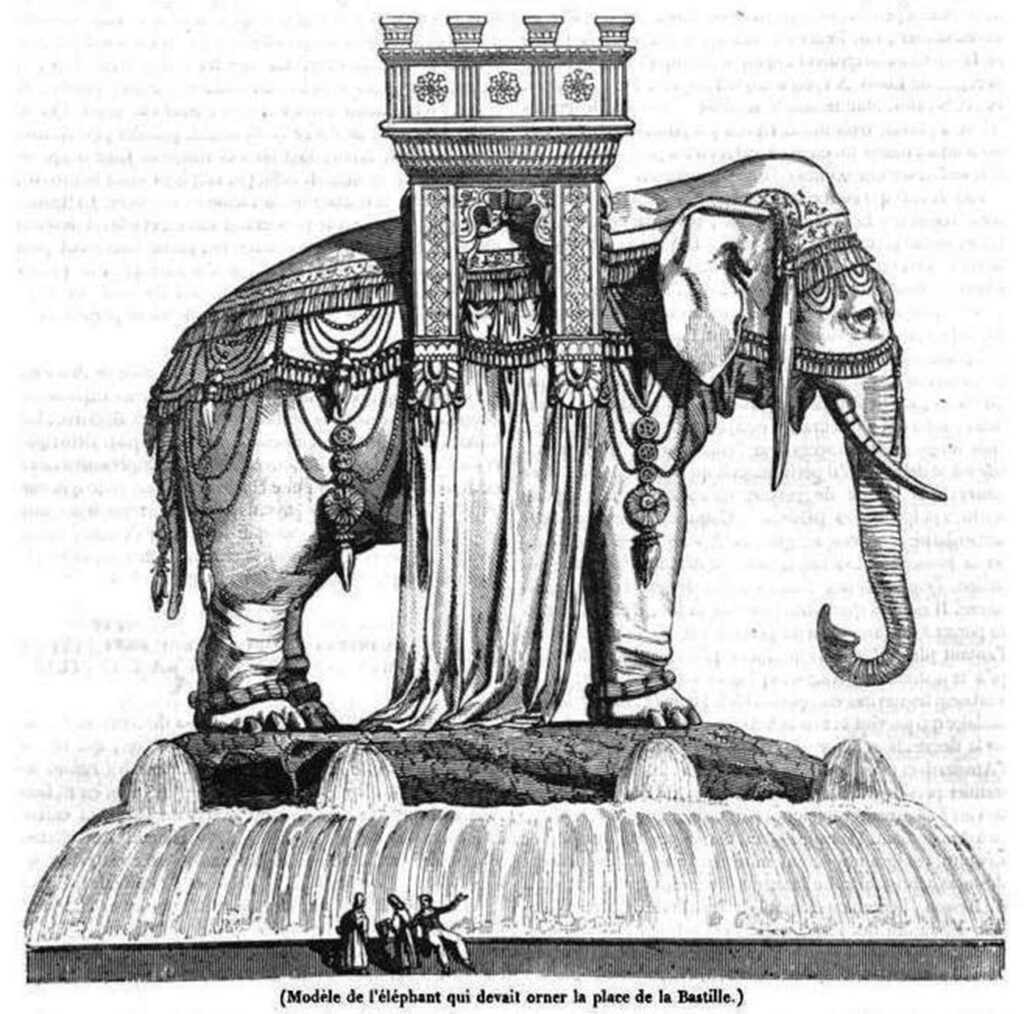

Of it, the city built a massive brick-and-mortar pedestal that still stands, where a monumental column (Colonne de Juillet) commemorates the Revolution of 1830. But before there was a column, a plaster full-scale model, hollow inside, of the Elephant of the Bastille (which was meant to be ultimately made out of bronze) was placed atop the surviving round pedestal built for this purpose.

The massive replica of the giant elephant, a project as excessive and meaningful as its promoter, reminded Napoleon of his beginnings in the French campaign of Egypt, and sought (not unlike certain leaders today) to place him in a long lineage of decisive, strong heads of state, from Hannibal (and his elephants crossing the Alps) to Alexander the Great. Then came Waterloo. Suddenly, no one in Paris wanted to pay for the massive elephant fountain, while its full-scale plaster model deteriorated in the cold, wet Parisian winters. Soon, it was so rat-infested that the surrounding population demanded it be taken down.

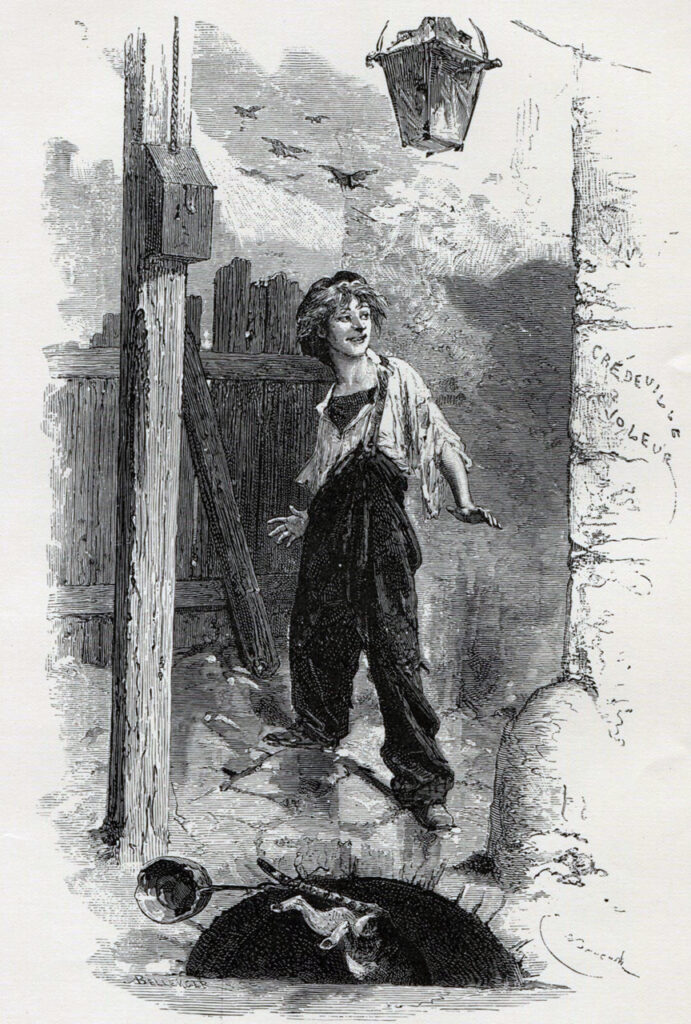

All in all, the Elephant of the Bastille presided over the very center of the square, where the infamous prison that started it all stood, from its placement in 1813 to 1846. But, as things go in France, the Elephant had an ultimate savior, who wanted to preserve its memory when it didn’t exist anymore, just like the psychogeography of places states: in the 1960s, a mature Victor Hugo, already a towering figure in world literature and with a grandfatherly body and white beard that would turn him later on into France’s eternal collective grandpa (almost France’s equivalence of a formal Santa, minus the Coca-Cola references), set to finish his postponed most ambitious project, Les Misérables. And so, when imagining the improbable dwelling of Gavroche, the book’s decisive and symbolic street urchin, he imagined the boy’s house inside… the plaster Elephant of the Bastille. And that’s what we explained.

Gavroche’s tiny house inside Napoleon’s elephant

It was a little homage to the city, but also a way for us to present gratitude to a writer who had died over a century before our time in the city: it was around those days, between the end of 2019 and the lockdowns of 2020, that Kirsten and I, each one separately, read Les Misérables. I enjoyed it grandly, and, as it has happened to me only a few times (I hope it happens more often in the future), I cherished every last page with a sense of unease, knowing that it would be different to get my hands on something like it again.

Of course, when we biked that afternoon to the Bastille Square, there was no elephant to see, and no prison either, but that doesn’t mean those realities have vanished for us and our culture forever. Napoleon’s unrealized elephant, a colossal monument cast from enemy cannons, meant to turn the stylistic restraint of the Convention and Directory years into extravagant spectacle after Bonaparte’s rise.

What stayed with us was not the monument that never fully existed, but the unintended interior it offered: a space born of excess and failure that briefly became inhabitable. It felt like a reminder that cities, like lives, are shaped as much by abandoned ambitions and improvised uses as by grand plans—that meaning often emerges not from what power intends to build, but from what people manage to inhabit along the way.

Victor Hugo’s description resonated with us, as we had it relatively fresh:

It was falling into ruins; every season the plaster which detached itself from its sides formed hideous wounds upon it. “The aediles”, as the expression ran in elegant dialect, had forgotten it ever since 1814. There it stood in its corner, melancholy, sick, crumbling, surrounded by a rotten palisade, soiled continually by drunken coachmen; cracks meandered athwart its belly, a lath projected from its tail, tall grass flourished between its legs; and, as the level of the place had been rising all around it for a space of thirty years, by that slow and continuous movement which insensibly elevates the soil of large towns, it stood in a hollow, and it looked as though the ground were giving way beneath it. It was unclean, despised, repulsive, and superb, ugly in the eyes of the bourgeois, melancholy in the eyes of the thinker.

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, 1862

Seen this way, Gavroche’s shelter inside the elephant reads less like an anecdote from nineteenth-century literature and more like an early instance of a recurring urban gesture: the carving out of small, human-scale refuges within the shells of oversized systems.

More than a plaster, rat-infested carcass of a sculpture

Long before we were interested in documenting parasitic architecture, micro-apartments, cabins, vans, or tiny houses, people were already inhabiting the margins of failed grandeur—repurposing monuments, infrastructure, and leftovers of power into places just large enough to sleep, think, and endure. These spaces are never born from abundance or fashion, but from necessity and imagination, emerging precisely when the distance between institutional scale and human life becomes unbearable.

In that sense, small dwellings are not a retreat from the world, but a quiet correction of it: a way of reasserting proportion when history grows too large, too abstract, or too indifferent to the body that must live through it.

Hugo imagines Gavroche’s shelter not as a room in any conventional sense, but as a hidden recess inside the elephant’s immense body, reached by climbing through a broken opening, somewhere between the legs or along the flank, where the plaster skin had cracked and time had hollowed the monument from within. Inside, the space is dark, damp, improvised—barely more than a cavity—but it is elevated above the street, protected from the rain, and, above all, invisible to authority. The boy sleeps there wrapped in scraps, surrounded by silence, rats, and the distant noise of the city, inhabiting what was meant to be a symbol of imperial grandeur as a tiny, fragile dwelling carved out of failure.

The contrast serves the author’s purpose: the colossal elephant, decaying (perhaps like France itself), hosts a witty, miserable urchin willing to give everything for the sake of principles (he later dies symbolically in the makeshift barricades). Perhaps the kid Gavroche is the archetype of the dispossessed, a descendant of the twisted, malicious Thénardier couple that, despite the odds, shows the honorability of a good soul (and the optimistic views of Victor Hugo himself regarding society’s reformation, much in the fashion of Jean-Jacques Rousseau).

When we see that the Elephant, a fake plaster carcass of a noble statue never built, ends up sheltering a child with nothing else but his instinctive principles, living hand to mouth, we realize that the story is fiercely alive, and there’s no ruin in any city if it serves as a shelter for someone.

The giant intentions of an honorable urchin: Gavroche’s timeless agency

Gavroche’s refuge is not sanctioned, not planned, not even acknowledged—it exists in the blind spot of history, in the leftover space of an abandoned ambition. It is a home born not of design but of necessity, a shelter made possible precisely because the grand project collapsed, leaving behind a hollow interior. When Gavroche sings, jokes, and dreams inside the elephant, he turns a monument into a dwelling, excess into subsistence, spectacle into survival.

This inversion—of monument into shelter, of power into refuge—speaks quietly but forcefully to our own time. Like Sartre writing in 1946, Hugo understood that history does not absolve us of responsibility; it merely changes the conditions under which we must act. Gavroche does not choose the world he is born into, but he chooses how to inhabit its ruins. He does not wait for permission, nor for a better order to arrive. He lives, improvises, persists.

We, too, live among the remains of grand narratives and overextended systems, in strange and dangerous times that often invite passivity, distraction, or resignation. Or worse: deep cynicism. Sartre’s insistence that we are “condemned to be free” was never meant as comfort, but rather the opposite.

After reading Les Misérables and helping Kirsten produce that video, the Elephant of the Bastille fell into the recesses of my memory. At least it did until recently, when, while visiting Antoine, an entrepreneur making machines to 3D-print buildings out of dirt, we entered his office, and I saw all sorts of memorabilia regarding an elephant that looked familiar.

I asked whether it was the Elephant of the Bastille. Yes—he replied. And an interesting conversation ensued. Antoine—an entrepreneur from Valenciennes, not far from Lille—saw the Elephant as a metaphor of many things as well, and had been fascinated by it since childhood. Perhaps flattered by my genuine interest on it, he gave us a copy of a book about this outlandish project that only created a replica.

Seeing the world like Les Misérables’ Gavroche (or like Victor Hugo)

Perhaps that is why the elephant feels at once so over-the-top and anachronistic, and at the same time prescient. Antoine’s fascination with it—like Gavroche’s occupation of its hollow body—was not nostalgic. It was practical, almost tactile. We spoke about scale, about matter, about what it means to build when resources are finite, and certainty is gone. His machines print walls from earth; Napoleon wanted to cast an elephant from cannons. Between those two gestures lies an entire philosophy of inhabiting the world.

In fact, Antoine wants to recover a replica of the Elephant built by the commune where he lives and later abandoned in a nearby forest; I thought he was pulling my leg when he explained it to me, but then he showed me articles and pictures of it. He’s currently building a little model 3D-printed village near his company’s headquarters, and “the elephant would be a perfect fit right in the middle of it all.”

What strikes me now is that small dwellings, whether improvised inside a decaying statue or deliberately designed on the margins of zoning codes, are not signs of withdrawal. They are responses. They appear when grand systems grow brittle, when abstraction overtakes care, when the distance between decision-makers and bodies becomes too wide. Like Gavroche’s shelter, they are often invisible to power, and for that very reason, they remain possible.

Perhaps that is all the repurposed elephant ever offered: not grandeur, not permanence, but an interior. A place just large enough to sleep, to think, to decide how to go on.

And perhaps that is still enough, if we are willing—as Sartre demanded—not to escape history, but to take responsibility for how we inhabit what it leaves behind. That might be the real meaning of psychogeography.

Giand and midget, midget and giant. The Elephant of the Bastille was conceived to depict Napoleon’s grandeur. Victor Hugo made sure it depicted the kid Gavroche’s grandeur instead.