Barcelona, 1986. The city held its breath: a small Mediterranean metropolis about to become a global stage, halfway to Columbus’s voyage and halfway to my own coming-of-age.

I was nine years old when, in October 1986, the IOC nominated Barcelona as the next city to host the Olympics after Seoul 1988.

It was a big deal to our city and the country, boosting collective self-esteem and instilling the sense of having a common purpose in the very year that marked the country’s imprint on the world stage, exactly half a millennium after the trip West that changed the world.

Six years passed from the moment Juan Antonio Samaranch proclaimed in Lausanne, “A la ville de Barcelone, Espagne,” to the torch being lit up at Montjuïc Olympic Stadium, and I was already in BUP (high school equivalent in Spain back then) in the summer of 1992.

Four years prior, the organizers of the 1988 Seoul Olympics performed the symbol of continuity of the modern Olympics by passing the torch to the organizers of the XXV Olympiad in Barcelona during Seoul’s closing ceremony. That was how, way before K-pop took over the world, kids in Barcelona got to know more about South Korea due to this apparently random factor, if only for the Seoul 1988 Olympics.

However, like Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return, the end of history was soon transformed into “the end of the end of history.”

When optimism about the middle class wasn’t far-fetched

Those were very different times for the psyche of the so-called developed world: the Eastern Bloc had crumbled in 1989 under the weight of inertia and internal division between reformers and hardliners, Europe sought a new era after Germany’s reunification and the groundwork for the European Union and the euro (Maastricht Treaty, 1992), and American soft power reigned supreme across the world. The West seemed to approach the end of history, and the future could still be more prosperous for the middle classes than the past.

But big shadows loomed over this portrait: neoliberalism was about to speed the hollowing out of industrial jobs in high-income countries, the wars of Yugoslavia were about to remind Europe of the fragility of any abstract ideology if nationalism and ethnic hatred were stirred up, and the middle class was about to be charged with singlehandedly maintaining the welfare state through taxes despite losing relative purchasing power, while companies and people getting their wealth from capital and not salaries (profits, dividends, rent, interest, etc.) benefitted from lower taxation.

However, things improved for many people in these societies, especially in countries that had recently joined the club, like Spain and South Korea. The trajectories of both countries were somehow related, as they had to develop and undergo major changes to become high-income societies in a shorter time than their peers. Though very different, both countries experienced a stark transformation in life expectancy, health, and education during the period.

As many high-income countries entered the nineties, their bigger integration into the global economy increased not only living standards but also augmented women’s participation in the workforce; a bigger percentage of people entering adulthood extended their education well into their twenties, delaying the biological window for childbearing.

And so, as countries like Spain and South Korea consolidated their concentrated urban population, children became rarer. Small cultural shifts and a lack of public awareness regarding the difficulties of entering adulthood made the perfect storm for a birthrate collapse.

When the shift manifests itself

Big societal shifts are hardly perceived as they happen. Structural trends first manifest like a receding glacier—imperceptibly at first, then suddenly reshaping the landscape around us. German author and soldier Ernst Jünger, a conservative who never acquiesced to the Third Reich and wrote about World War I trench warfare, reminded readers that slow, imperceptible shifts accumulate unseen until they erupt dramatically. Fertility trends are no exception.

And so, without anybody paying attention, the buildings to host public schools that Spain had built in its urban areas during the seventies and early eighties, packed with children until the late eighties, began to feel empty when I hit my teenage years. In my hometown, ten kilometers away from Barcelona, the school I attended had to merge with the school next door and eventually shut down a few years later. The motive: the boom was over, and people didn’t have as many children anymore. And a new trend that should have been more concerning arose: many adults didn’t bother to have any kids at all.

It’s hard for us to grasp, but what seem abstract trends do have a translation into reality, no matter how effectively we are trying to overlook such evolutions. Rough structural trends in a country are not just abstract numbers in reports—they manifest in everyday life and shape what we see on the street.

For example, as Spain experienced a sharp decline in fertility during the 1990s, this demographic shift was visible in neighborhoods, schools, and public spaces. Families were having fewer children, and the effects were tangible: playgrounds had fewer kids, classrooms were smaller, and local kindergartens often had empty spots. The decline in births wasn’t just a statistic; it changed the rhythm of daily life and the texture of communities.

Growing up as a teenager in Spain during that period, I could feel these changes firsthand. The streets seemed quieter, and the usual bustle of children heading to school or gathering in parks was noticeably thinner. Shops and services that once catered to large families saw fewer customers, and the societal infrastructure gradually adjusted to the new reality.

This experience made clear that broad demographic and economic trends, such as declining fertility, are not distant abstractions—they ripple outward into neighborhoods, schools, and everyday routines, shaping the lived experience of entire generations.

Fertility trends after the Spanish Civil War

I was the second of three siblings (one older brother, one younger sister, all of us five years apart), and I remember how habitual that was at that time and place; almost all of our friends had at least one sibling, and many of them had two.

I have to admit that, in Barcelona’s late-eighties and early nineties, families with four children were rather rare and, according to non-spoken stereotypes that didn’t reflect reality but surely told something about it, they belonged to two main categories on both extremes of the social ladder: very religious Catholic families that could afford having many kids (read: Opus Dei), or very poor, unstructured families wary of the use of contraceptives.

Having four children (in a traditionally Catholic country during Franco, that is, “National Catholic,” that meant four children and a couple married and living together unless some disaster had hit) was relatively normal in post-Civil War (1936-39) Francoist Spain.

The country struggled with economic autarchy and isolationism from the early forties to the late fifties, an international pariah due to its connection to the Axis powers until the end of World War II, and then a convenient “anti-Communist” power above all in the context of the Cold War, and therefore finally accepted into the UN in 1958.

Early on, Franco’s regime implemented the “familia numerosa” policy to encourage the population to have large families, offering marginal support to those with four or more children. Things didn’t officially change until the arrival of democracy, when the country had developed, its living standards were rapidly converging with those of peer countries, and families shrank in size by the time Social Security, modern medicine (efficient and universal, set up pre-democracy), pensions, and social housing elevated the country’s middle class during the early 1960s.

The country experienced its very own economic miracle (a “milagro económico” led by young Opus Dei technocrats controlling the regime, or “Movimiento Nacional”), and many things experienced rapid change: people could go to college, buy cars, have vacations and second residences, and become more secular. Young people from rural Spain moved to the city to work in factories, buying apartments and having three children (or fewer) instead of bigger farming families in the countryside.

First, families get smaller; then, they stop being viable

So, what we observed around us growing up was more than the feeling of an underlying symptom: the country’s birthrate was rapidly transforming before our eyes, and as we became teenagers and went to college, younger parents were already having two children maximum, and many of younger first cousins (and their friends) were only children, some of them living with only one of their parents after more frequent separations and divorces.

In 1994 (right before I started college in 1995-96), the Spanish society, now a mature, post-Olympic democracy and midsize power within the European Union after the more populous reunified Germany, the UK, France, and Italy, came to terms with the new reality: nobody was having four kids anymore, so it began to consider families with three children as a large family (“familia numerosa”), a reality shift. It was formalized under Law 40/2003 on the Protection of Large Families, which aimed to establish a nationwide standard in the context of the heavily decentralized modern Spain.

I finished college in 1999, began working soon afterwards, and got my own rental in 2002 or so, first with a local girlfriend and then on my own at a Gothic Quarter’s mansard in central Barcelona. I met Kirsten in 2004, and we married in Barcelona in June 2006. Our first kid was born in 2007, our second in 2009, and our last one in 2012, all of them in Barcelona, acquiring both the Spanish and US nationalities from the start.

Now, families with young children are aware that, when one is raising toddlers and young kids, that permanent awareness and energy is difficult to bear for people who aren’t at the same life stage, so everybody with young children would cluster together, and that really narrowed our social perception for a while, but I stayed aware of the country’s birth rate crisis by just observing all my old friends from the town near Barcelona where I grew up, as well as my college friends.

An overwhelming majority didn’t leave their parents’ place right away, as youth unemployment remained high across the region and was especially acute in Southern Europe, many didn’t have a stable couple and even fewer married, let alone have children before hitting their late thirties. So, by the time some friends were ready and willing to have a family, human biology was about to hit, and having two children became rare. Perhaps in 2030, Spain will declare two kids the new “familia numerosa.”

When we became a “large family”

When our son was born, we collected our card for “large family” (familia numerosa), which meant paying less at events and some household investments, but nothing life-changing. That said, we were rare in Barcelona, and the parents we hung out with (especially Kirsten, who is more social than I am) were raising one, perhaps two kids, almost never more than two. Also, many couples having children weren’t officially married, and many of them weren’t together anymore after a few years.

My real-life observation of the reality of young professional families in urban environments didn’t end up in Barcelona. In late 2015, when our youngest had just begun Elementary School, we moved to Fountainebleau, a small, gentle town surrounded by a forest one hour South of Paris with a sizeable international community that had a bilingual school English-French (with the option of learning Spanish as a foreign language) and where we figured our children could perform a soft cultural landing into another society and environment.

Soon, by just attending the events at our school and the few extracurricular activities we signed up for right away, as we started the school year two entire months late, we noticed that families with three children weren’t as rare as they seemed in Barcelona, even though many of our friends and relations had two children. There, we also saw families with four children, some of whom were growing up at home with half-siblings (we saw this in Paris A LOT later on).

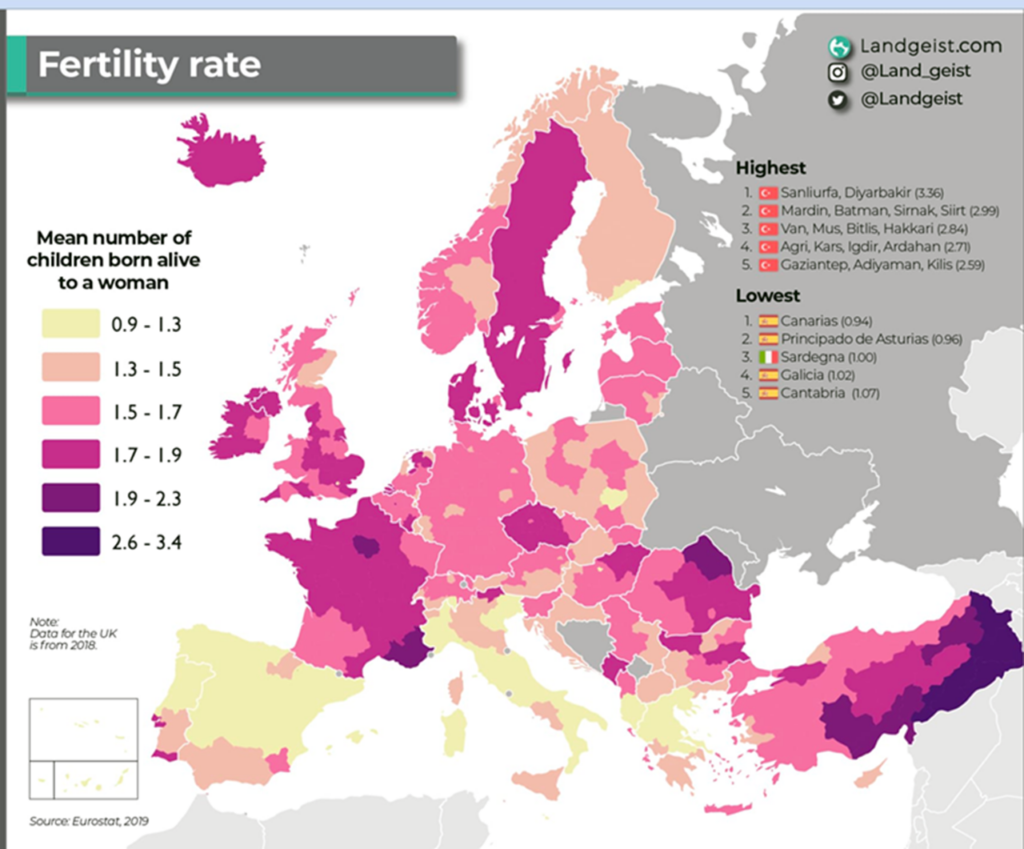

Curious about my impressions, I asked around and read about birth rates across Europe, and observed around us how France’s decades-long, nationwide effort to encourage families to have more children had actually worked. Now, many cynics and outright pseudo-eugenicists (after all, the ideologue behind the pseudo-theory of the so-called “Great Replacement” is Renaud Camus, a French author) will try to tell you that France’s higher birth rates with respect to peer European countries, and especially compared to its Southern European neighbors, have to do with immigrants and children of immigrants exclusively, for they monopolize all new births and therefore siphon all the social aid there is. This is false, and we’ve observed it with our own eyes, for many of our friends and acquaintances of French origin had more children overall than our friends in Spain and even the United States.

Prohibitively expensive regions are indirectly anti-natalist

This new observed reality happened to coincide with an extensive trip we did across Japan when our children were still young (and, therefore, our perception was biased towards other young families with children to cluster around, as they are more tolerant of toddler energy and noise).

It didn’t take long for us to notice many easy-to-spot trends that held in Japan (also in Osaka, Kyoto, and other cities we visited) and the countryside. The first thing we noticed was a perceived sense of order and gregariousness, some sort of collective organizing that the urban Japanese seemed to perform with no complaint whatsoever.

Another thing that puzzled me right away: there seemed to be more old people around us, old people seemed more active than in Europe and especially the US, and few older people seemed to deal with visible morbidity issues.

Thirdly, young families with young children were less frequent, but not less so than, say, our reality experienced in Barcelona. I figured that South Korea may face a similar reality.

I wonder whether adults of my generation (late Generation X, and early Millennials) from South Korea would explain a very similar reality and evolution growing up. Both countries (the one behind the country-wide proud achievement of 1988’s Seoul Olympics, the one behind 1992’s Barcelona Olympics) were showing the world what it looked like to be and behave as a “developed” society. Then, many things must have gone wrong for the expected low-but-manageable birth rate to tank to concerning levels and remain so to this day.

After moving to the Bay Area in mid-2022, we faced a new learning curve concerning a new school system, though this time we played with some advantages, since Kirsten grew up here and our children had visited every year and are culturally fluent in the main realities they face every day. It’s expensive to live here, and many young people find it challenging to thrive in places where they barely get by on their own. Having children becomes more difficult, and having many children is, at least in some areas, a sign of affluence. Overall, even if the Bay Area’s birth rates vary by county, the metro region has a lower birth rate per 1,000 population than California as a whole, while California’s birth rate is lower than that of the US as a whole.

Playgrounds with more parents than children

Many of the challenges faced by my friends in Spain are also affecting people living in expensive areas across the world. The Bay Area’s fertility rate is among the lowest in California due to many factors, but it would be naïve to think that there’s no relation between housing costs and the professional lives of high achievers and the precarious decision to delay childbirth because they think they can’t afford to have bigger families.

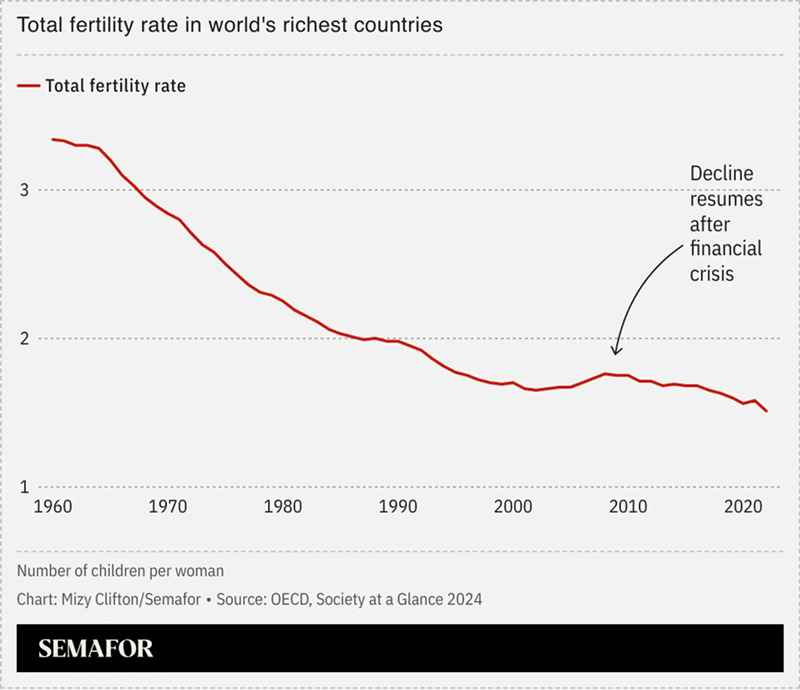

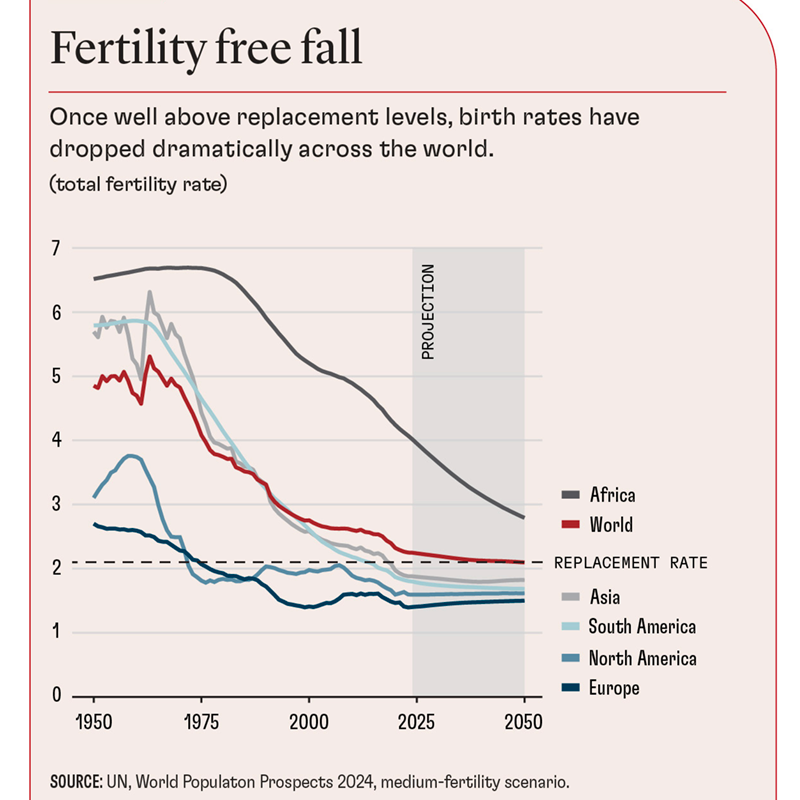

That said, the total fertility rate in the United States in 1977 was 1.8 children per woman (down from 3.65 children per woman in 1960 at the end of the baby boom), having dropped below replacement level (2.1) for the first time in 1972. It rebounded slightly in the 1980s and peaked around 2.1 in 1990; but a perfect storm of high expectations, rising college education tuition, a financial crisis, and a pandemic may have played a role in a fertility rate of 1.6 children per woman.

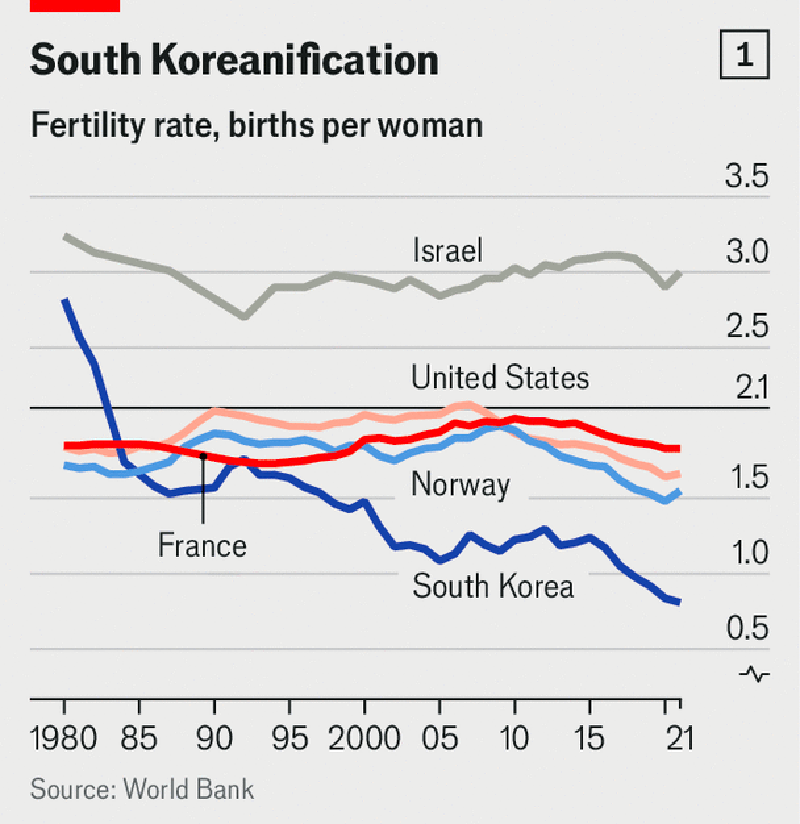

In 1977, the year I was born, Spain and South Korea’s fertility rates were still higher than in Japan (the country South Korea looked up to) and the rest of Western Europe (Spain’s natural region as it joined along with Portugal the European Economic Community—later European Union— in 1986, the same year we found out about the Olympics). Both countries’ birthrates were well above the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman for country populations not to shrink over time: 2.65 in Spain, and even higher (3.0 children per woman in South Korea).

By comparison, in 1977 Japan had a birthrate of 1.80 children per woman, France 1.94, Italy 1.93, and Germany and the United Kingdom had even smaller fertility rates back then, well under the replacement level (1.4 children per woman in Germany, 1.66 children per woman in Great Britain).

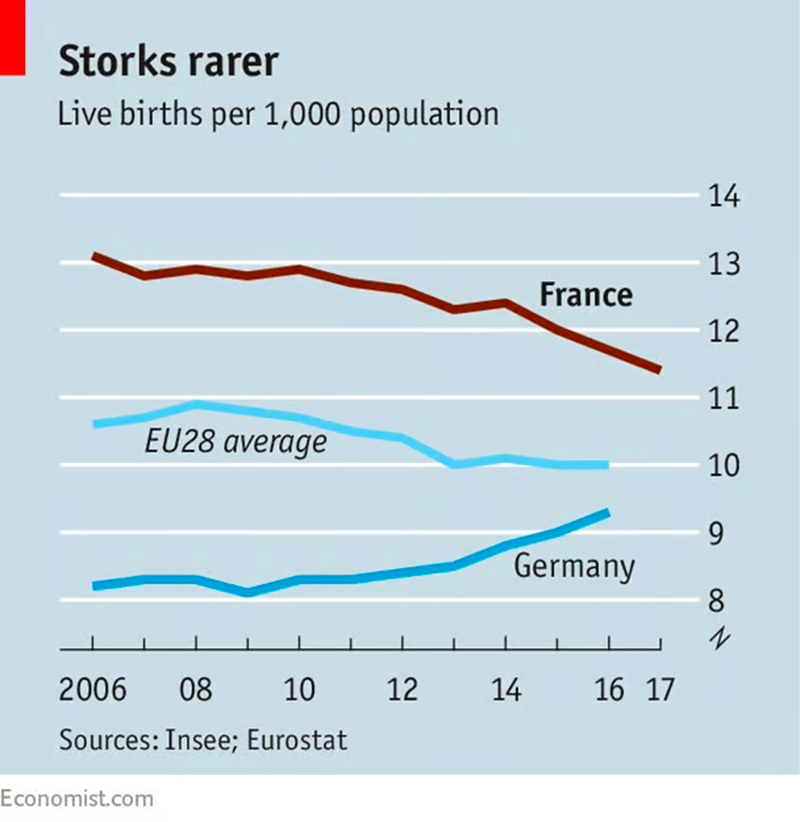

Over the last five decades, while the fertility rates of the UK and Germany have increased slightly, albeit still below replacement levels, Japan, South Korea, and the Mediterranean countries of the EU have experienced the steepest decline in fertility rates. France, however, inspired by the Swedish pro-natalist model, established more aggressive policies to encourage families to have more than one child, which explains the difference between France’s 1.85 (or Sweden’s 1.84 children per woman and Spain or Italy (1.12 and 1.31 children per woman, respectively).

Low birth rate and longevity

There are more parallels between the progression (or perhaps “stasis” is a better term) of Japan and South Korea since the late seventies and what Mediterranean Europe experienced during the same period: as the fertility rate dropped, their populations aged, becoming somewhat of a longevity outlier for their overall populations.

Thanks in part to their actively pro-natalist policies, both France and Sweden have slightly higher fertility rates than the US estimate for 2025 of 1.79 children per woman; interestingly, Canada’s fertility rate was identical to that of the US in 1977 (1.78 children per woman), but it shrank to 1.26 nowadays.

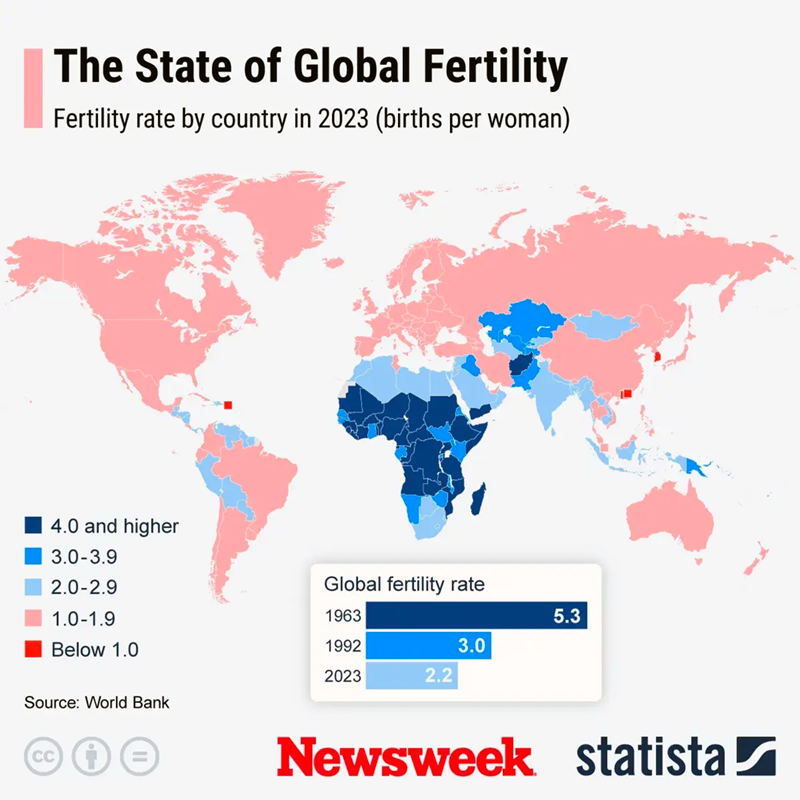

Overall, the fertility rate among Americans has remained relatively stable just below replacement level, just like that of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. By contrast, Mediterranean Europe has experienced substantial declines and is today in a more worrying territory, whereas Japan and South Korea are absolute low-fertility outliers.

An interesting fact: among the 10 countries with a highest life expectancy today (Japan, Switzerland, Singapore, Spain, Italy, France, South Korea, and Australia), only France hovers slightly below the replacement level of fertility at 1.85 babies per woman, whereas the other countries are further away from the desirable inflection point in natality that allows societies not to shrink and get older faster than desired, affecting their ability to keep a robust social contract and high pensions for the elder (which get paid with the shrinking working population at a younger age).

A country packed with centenarians

Another fact one can extract from the life expectancy country outliers is the increased percentage of people hitting elder age with prospects of having many years of reasonable health and social participation ahead of them. As we observed during our trip to Japan, the Asian country is the world’s outlier in this trend, explained by BBC:

The number of people in Japan aged 100 or older has risen to a record high of nearly 100,000, its government has announced.

Setting a new record for the 55th year in a row, the number of centenarians in Japan was 99,763 as of September, the health ministry said on Friday. Of that total, women accounted for an overwhelming 88%.

Japan has the world’s longest life expectancy, and is known for often being home to the world’s oldest living person – though some studies contest the actual number of centenarians worldwide.

It is also one of the fastest ageing societies, with residents often having a healthier diet but a low birth rate.

Interestingly, in the 1960s Japan was the G7 country with the lowest proportion of people aged over 100. Things have changed dramatically:

The higher life expectancy is mainly attributed to fewer deaths from heart disease and common forms of cancer, in particular breast and prostate cancer.

Japan has low rates of obesity, a major contributing factor to both diseases, thanks to diets low in red meat and high in fish and vegetables.

The obesity rate is particularly low for women, which could go some way to explaining why Japanese women have a much higher life expectancy than their male counterparts.

As increased quantities of sugar and salt crept into diets in the rest of the world, Japan went in the other direction – with public health messaging successfully convincing people to reduce their salt consumption.

But it’s not just diet. Japanese people tend to stay active into later life, walking and using public transport more than elderly people in the US and Europe.

Nobody knows the exact recipe to boost fertility rates

There’s a fundamental principle in statistics and the scientific method that reminds us that correlation is not causation: because two things appear to go together, sometimes we assume they are related phenomena or they happen together, or there’s a relationship of causality among them (one influences or originates the other), but many times the two things or events don’t show an actual cause-and-effect link.

A question arises: Is there a causal relationship between low fertility rates and people living longer in places such as Japan, South Korea, and Mediterranean Europe? Even if there’s no direct causation between both trends, low fertility rates often go along with people living longer, as they appear in high-income societies that have extended welfare states reaching their entire population.

Such underlying developments are causing low fertility and high longevity: overall economic development, women’s better education and empowerment, healthcare improvements, and access to community networks that keep people connected to reality. In this final point, Mediterranean countries and Asian outliers, such as Japan and South Korea, excel compared to more individualistic, wealthy societies like those conforming to the Anglosphere.

After all, concepts like ikigai, dolce vita, savoir vivre, el buen vivir, or Greece’s Καλή ζωή (“kalí zoí,” literally “good life”) aren’t just social media trends but the popular expression of deep cultural beliefs that allow people in Japan or along the Mediterranean to enjoy a life rhythm and a sense of community that contributes to overall quality of life and longevity, and many times this increased quality of life doesn’t correlate with higher wealth.

And here’s the thing: No one knows the exact recipe to boost fertility rates—like a secret sauce passed down through generations—but we do have a rough idea of the ingredients. Japan, South Korea, and Mediterranean Europe are experiencing population stagnation, but such societal stasis doesn’t correlate with decreased quality of life for the overall population, especially the elderly. Advanced healthcare, healthy diets, active lifestyles, stronger family ties and relationships are contributing to longer lifespans.

World of yesterday, world of tomorrow

Given the concerning consequences of having fewer young people to contribute to society with their productive lives, and therefore helping countries pay for their growing, healthier elder population, here’s a question worth exploring: how can the most successful regions where people live fulfilling lives for a much more extended period increase their fertility rate?

While far from perfect, the case of Sweden and France, countries that increased their fertility rates from the 1960s onwards with active structural policies that mainly worked, shows some clues: having more children can be very expensive, so France and Sweden provided cash subsidies and allowances to families having more children, as well as tax benefits and housing support.

Additionally, policies that reduce the burden on mothers raising children have benefited both countries, even as more women pursued higher education and started professional careers. Paid parental leave, accessible childcare that people can afford (the “crèche” model in France), and more flexible work arrangements have all helped young families.

These policies aren’t rocket science; they just recognize that, in developed societies, people want to have kids but are often deterred by financial and social pressures.

The most effective strategies seem to be those that create a supportive environment where having a family doesn’t mean sacrificing one’s career or economic stability. Unlike the hashtag #tradwife, these factors are data-backed and have worked in entire societies over decades.

As I watch my children grow, I sometimes wonder how the choices of their generation will shape the streets they walk on, the schools they attend, and the cities they call home. Statistics may predict trends, but life is lived in playgrounds, classrooms, and quiet kitchens, where each child is a small, visible hope for the future.