Hot springs have soothed bodies and shaped cultures from Scandinavia to Japan for thousands of years. But the same ancient warmth that created convivial bathing could reshape the world.

There’s something primordial about getting in a hot spring amid nature. Many cultures have turned the activity into a refined cultural treat since time immemorial.

To others, the contrast of combining the outdoors in winter, warmth, and slowness has turned into an art in some places, to the point of becoming part of the national character.

In Finland, saunas helped women go through delivery, and the mere idea of hot, steamy baths in nature is associated with complex, soothing semantics such as “hygge,” a Scandinavian concept widely used in Denmark and Norway that describes a particular type of coziness, warmth, comfort, and well-being: it evokes a feeling as much as an abstract perception of conviviality.

Hygge in hot water & Japanese onsens

Though not originally part of the Danish definition of hygge, warm springs and their human-made counterparts (saunas, even hot tubs, a mere steamy bath or shower at home) often, in association with cold plunges, create the same emotional atmosphere that gives meaning to the concept. Like hygge, natural warm springs and saunas—often taken after a demanding day or activity—provide a cocooned atmosphere of warmth, comfort, and protection from the cold or chaos outside.

Also like hygge, hot springs bring people together through quiet rituals: sitting in silence, alternating hot and cold, sharing a story, or sipping a comforting beverage, often tea. The Nordic connection between the protected indoors and the experience of the outdoors gives meaning to the idea of “friluftsliv” (open-air life), even as modern life makes traditional ways of life more difficult.

In the other extreme of Eurasia, the Japanese onsen is the traditional setup for a cozy, warm bath. When we visited the country a few years back, we experienced them while traveling in the countryside, sometimes choosing “ryokans” (a traditional type of inn with tatami-matted rooms around courtyards with zen gardens and little zen and shinto shrines) over their contemporary counterparts.

When we visited the Hōshi Ryokan in Ishikawa Prefecture, an establishment founded in 718 and managed by the same family for 46 generations, we could feel the weight of ancient springs in Japanese culture.

Lessons from snow monkeys

It wasn’t winter when we stayed at Hōshi Ryokan, but we realized nonetheless that people went there to slow down and shove off the frantic world outside. It was an effective, unassuming way to practice calm breathing and reconcile oneself with a primordial sense of well-being.

There’s even a concept to define this sensation: “yuan” or “yuagari,” the sense of warmth (in body and spirit) after a bath 湯上がり. During our visit, Zengoro Hōshi mentioned the concept Ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会), meaning “one time, one meeting.” A meeting with a customer or a friend never repeats, and it’s something to cherish casually. Here’s the video on our visit.

It must have been after our trip to Japan, but when I saw social media images of Japanese macaques enjoying their natural hot-spring baths in absolute conviviality, it made me smile. These animals, known as Nihon-zaru (medium-sized monkeys with thick, fluffy fur that ranges from gray to brown), also called “snow monkeys” because they live in snowy regions, soak in groups in places such as the hot springs of Jigokudani Monkey Park. After seeing the pictures, I realized that this activity is much more primordial than I had thought. Why shouldn’t it?

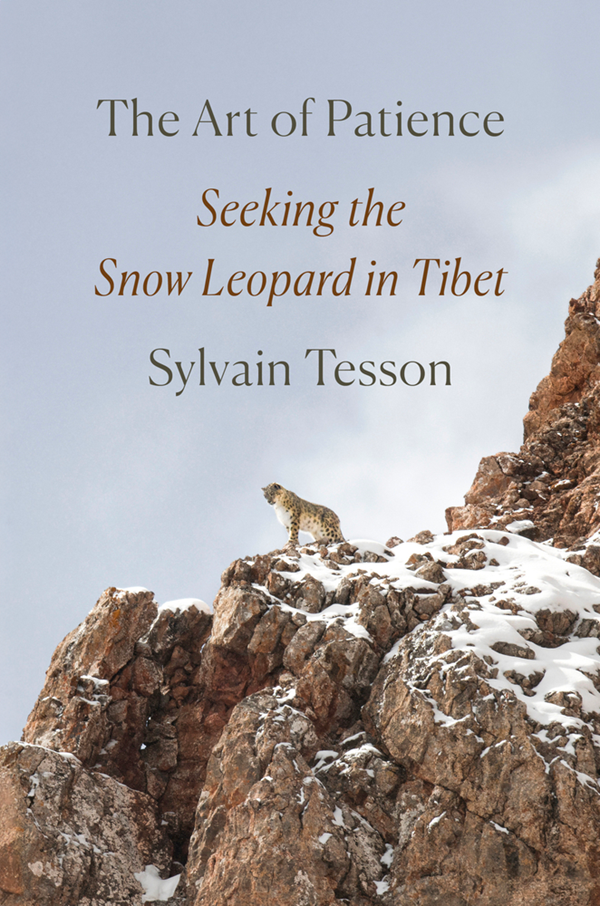

There’s a little book by French travel writer Sylvain Tesson that recently made me feel in all this again, while putting a smile on my face. In “The Art of Patience: Seeking the Snow Leopard in Tibet,” Tesson travels with photographer Vincent Munier and two other friends on an elusive quest to find the snow leopard in the high, rocky passes of the Tibetan Plateau.

As usual, Tesson uses a very hands-on adventure to explore deeper questions that bother us all, or what we may call the “human condition.”

Into the primordial soup

And so, after spotting the majestic and solitary snow leopard several times (unlike—Sylvan Tesson writes—legendary wilderness writer Peter Matthiesen, who had left Tibet without seeing the animal once), Tesson and his friends drove toward Yushu to treat themselves in the freezing temperatures (constant —25/-30°C) with a thermal-springs bath.

The chapter is conveniently titled “In the Primordial Soup,” and explains that they get to the place at night after an exhausting journey:

At 10 P.M. we pitched camp in the shelter of a slope, it was -25°C, then Marie, Munier and I splashed in the scalding water, invisible in the clouds of steam. Up above, whipped by the wind, Léo watched over the camp. The water gushed beneath an indent in the rock. We had had to slide along the overhang. Munier was familiar with the place, having played the Japanese macaque here the previous year. He described the snow monkeys that frequented the hot springs of Nagano, steam blurring their red faces, wet tufts of hair turning to stalactites.

But, that night, we looked more like Russian apparatchiks in a sauna divvying up the resources of the region. We lit some Cuban cigars (Epicure No. 2) that we had kept safe in aluminum tubes. Our skin took on the texture of a toad’s belly and our Havanas the texture of marshmallow. The stars shimmered.

“We’re splashing in the primordial soup,” I said. “We’re bacteria at the dawn of the world.”

“We’re a little better off,” said Marie.

“Bacteria should never have crawled out of the cauldron,” said Munier.

“But then we’d never had Beethoven’s Triple Concerto,” I said.The fossils embedded in the vault did not date from the beginnings of the world. They were merely a recent episode in the adventure. Life had been born of the globe of water, matter and gas that formed 4.5 billion years ago. Biotics proliferated in every nook and cranny without any apparent semblance (beyond the will to propagate), thereby creating lichen, rorchuals and us.

The whorls of cigar smoke caressed the fossils. I knew their names, having collected them between the ages of eight and twelve. I said them aloud, since scientific taxonomy serves as a poem: ammonites, crinoids, trilobites. Some of these creatures were more than 500 million years old. They had reined. They had had their concerns: defending themselves, feeding, perpetuating the species. They were mostly small and distant. They had disappeared and we human beings who ruled the earth (from a recent date, for an undetermined period) paid them scant attention. And yet their lives had been a stage on the road to our appearance. Suddenly, living creatures dragged themselves from the bath. A few—the more adventurous—had crawled onto a shore. They took in a mouthful of air. And it was to this breath that we, humans and other animals of the open air, owed our existence.

The Art of Patience: Seeking the Snow Leopard in Tibet, Sylvain Tesson, English edition by Penguin (2021); from the chapter “In the Primordial Soup,” pp. 172-173

And, of course, Tesson doesn’t waste the opportunity of teasing himself when the moment of getting out of the hot pool comes:

Getting out of this bath was not one of the more pleasant moments of my existence. I had to walk naked across warm algae, jump into my Chinese boots, pull on the huge fur-lined jacket and make it back to the tent in temperatures of -20°C.

That is: drag myself from the soup, crawl through the darkness, find shelter: the story of life in a nutshell.

The Art of Patience: Seeking the Snow Leopard in Tibet, Sylvain Tesson, English edition by Penguin (2021); from the chapter “In the Primordial Soup,” p. 173

Steam cities of the world

Across cultures, the attraction to hot springs is much more than a simple, thermal appreciation for “warm water.” It taps into an ancient human instinct of cozy places where people can slow down, reconnect, and feel protected from the elements if only temporarily, for thermal baths are often used along with cold plunges or in winter environments since time immemorial.

In a way, long before the appeal of hot springs, saunas, and hot tubs in pop culture, geothermal bathing served as natural “public living room” heated by the earth, giving way to traditions such as hygge and onsen conviviality in Scandinavia and Japan, respectively.

When in Japan, we never made it to Kyushu, the southwesternmost of Japan’s three main islands. Known for its active volcanoes, Kyushu holds one of the best-kept secrets of local culture around hot springs.

With a population of 113,000 people in over 60,000 households, Beppu is known as “steam city.” Imagine if there were a city built in the geyser area of Yellowstone. In Beppu, geysers explode skyward near scenes of quotidian, contemporary living, a reminder that Japan’s volcanic activity is a part of the country’s collective unconscious.

Thousands of hot springs have kept the area at a constant boil since early human settlements during the Jōmon period (or Japanese neolithic). In a way, Beppu is a city built around an ancient tradition, but it also speaks about a possible low-high-tech future in which human settlements connect to the untapped heat and energy generated within mainly underground reservoirs of steam and hot water.

Where the earth boils underfoot (and boils eggs)

In places like Beppu, however, these reservoirs reach the surface across the city, and the town—home to more than 2,000 onsen—has turned the casual activity of bathing in nutrient-rich water, mud, and sand into an art.

To the visitor, Beppu might feel a bit like entering a different, laid-back dimension. According to authors chronicling the experience, it’s normal to see people barefoot in slides and dressed in kimonos, grabbing something at the nearby supermarket, blending conventional groceries with local staples such as a packet of bath salts and bags of flower essence.

What’s even more interesting, hot springs are so widespread in Beppu that there’s no entry barrier to such an ordinary activity: people from all socioeconomic backgrounds enjoy casual talk amid the clouds of steam rising from the street like a giant pot of boiling water: in Beppu, it’s not a proper day if you haven’t had a steam bath, even if it’s short.

Some of the spa-style hot springs are free and managed by the town, though hotels and guesthouses (both traditional and state-of-the-art) have their own private onsen, too, allowing locals and visitors to choose from different types of pools and thermal baths, surrounded by steam puffs rising everywhere.

The town’s different hot-spring districts—Kannawa, Myoban, Kamegawa—have unique mineral profiles, so people often switch bath areas depending on how they feel and the alleged properties of each area that are said to aid their well-being. But bathing isn’t only about getting clean in body and soul; it’s also a complex form of community maintenance, neighborhood cohesion, and intergenerational conviviality, thanks to places like public footbaths where visitors and residents dip their feet in hot water while reading the paper or chatting.

In the hills nearby, a beautiful pool hovers over the small city, shimmering cobalt blue. There, the water is 98°C when it gushes out of the ground, so locals and amused visitors boil eggs in it as a tradition. The pool’s cobalt blue contrasts with the colors of other natural hot springs in the area, ranging from milky white to clay red, depending on their chemical composition.

The ancient warmth we forgot to use

Connoisseurs in the area know that each hot spring has its own temperature, pH, and salt concentration. Water can be especially good for certain skin conditions in some places, whereas other places are known for enhancing blood circulation or soothing the nervous system after a demanding day of work. In other words, hot springs are a part of people’s lives.

Beppu is a reminder that, even as local cultures have benefitted from their thermal pools since time immemorial, human culture has barely begun to consider the untapped potential of geothermal energy to heat and power entire cities at a fraction of the cost of other energy sources, causing little to no pollution.

Underneath the everyday normality in which the local population of cities like Beppu, Reykjavik (Iceland), or Rotorua (city in the North Island of New Zealand), lies the still-unrealized promise of pioneering geothermal energy at a civilizational scale. What feels ancestral, almost mythological in hot-spring towns, is in fact the most modern of possibilities: a direct line to clean, constant, renewable energy flowing from the planet itself.

For decades, geothermal was merely a geological curiosity—reliable only where the crust is thin, and too expensive and risky elsewhere, though something has decisively changed. Thanks to the convergence of technologies that weren’t meant for energy at all: deep directional drilling developed in the oil industry, fiber-optic sensing from telecommunications, and enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) designed to create engineered reservoirs where none naturally exist.

Recent articles by The Economist and The New Yorker explain the change. Geothermal today feels like wind and solar power in the early 2000s: a technology seen as niche until innovation abruptly made it scalable. If the barrier to pervasive, reliable geothermal energy was access—the ability to reach that heat safely, cheaply, and predictably—, that barrier is now beginning to fall.

The planet’s quiet, clean power plant

The warmth that once invited Jōmon settlers to bathe in Beppu’s springs is the same warmth that could deliver the holy grail of clean energy: 24/7 baseload power without carbon, intermittency, or dependence on weather. Unlike solar and wind, geothermal is always on. And unlike fossil fuels, it does not require burning anything, moving anything, or destabilizing the climate to keep lights on.

Cities like Reykjavik already run almost entirely on geothermal heat. Boise, Idaho, heats its downtown district with hot water circulated beneath the streets. In Japan, even as the country remains cautious about tapping geothermal for electricity due to its high number of sacred and protected springs, innovators are quietly demonstrating that EGS could allow future plants to sit far from traditional bathing areas—coexisting with cultural heritage rather than threatening it.

Entire regions could become areas with free energy thanks to geothermal power working as an efficient giant heat pump. Eventually, the whole planet could become a battery charged by the free energy released from its core.

For generations, humans turned to geothermal heat for solace, ritual, healing, social bonding. What modern geothermal engineering proposes is not so different: a return to the earth’s inner warmth, but this time to power our cities, stabilize our climates, and perhaps cool our geopolitical anxieties.

It is as if the comfort of the bath—its quiet, its warmth, its sense of security—were being scaled up to the level of infrastructure. Perhaps we’re sitting on much more than vents and hot, sulphureous water pools used as spas for body and soul. We should be thinking about homes, factories, and everything that needs power or heat to function.