What if a text read like a slow walk? The truest form of luxury is not online but contemplative. Autumn invites both preparation and pause, strategy and reverie.

To many, Fall is a moment of strategy and anticipation: booking trips before prices rise, finishing the last chores before winter, arranging our children’s lessons, and trying to make ends meet.

Yet it is also a time for reverie. As the days shorten and the light softens, we look inward — “In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy,” wrote William Blake — and we long for the kinds of growth that have nothing to do with productivity.

There are, of course, more utilitarian ways of seeing this time of the year, but few things feel more liberating than a walk and a conversation with a friend, or perhaps an introspective outing, all for the sake of daydreaming or saying aloud some outlandish plans for the future. Maybe a better garden, a property overhaul, a trip abroad, learning a new skill, designing and building a cabin with one’s own hands?

One transformative outing accessible to anyone

Sometimes, all it takes to switch perceptions and shake the gloom is to head to the trees nearby. Consider, for example, how people like English forest forager and divulgator Fergus Drennan transform themselves by venturing in the forest nearby and opening the portal to a universe that has contagious energy and sensorial bounty; we experience the way his perceptive knowledge expands in the forest when we took a walk with him, feeling we had entered a totally different realm.

Now, experience the same conversation or walk with a different mindset and without predisposition, and the experience will become so impoverished that you will wonder why the same activity can feel so different. There is only one possible response: it’s the way we look at things.

To British writer Robert Macfarlane, the paths near our home connect us with the land’s “memory,” and walking them, we become a part of that same memory, both literally (by using a path, we maintain it, preventing weeds from erasing it) and poetically. Perhaps the best advantage of having a dog is that it prompts people to explore their surroundings with fresh eyes and a shared enthusiasm.

Attitude and a genuine sense of curiosity, whether trained or not, help us reenchant the world and likely benefit our mental and physical health, as evidenced by studies on walking in nature and improved long-term health outcomes. Eastern cultures even have a name for it, “forest bathing.” One study found that a one-hour walk in a natural setting (versus an urban setting) reduced activity in the brain’s amygdala, a region linked to stress and negative emotion.

Fresh eyes

Personally, even if there were no evidence of it regarding our health, I just enjoy exploring the paths and mountains amid urban adjacent natural spaces, which in areas like the San Francisco East Bay may bring some interesting surprises like spotting bobcats and (surprise surprise), California condors, back in the area after a 100-year absence.

It’s not an accident that our working title for the book Life-Changing Homes was Reenchantment, though we were told it was too obscure and vague a term to title a book; it was clear to us, however, for the meaning we were trying to convey was somewhere in the intersection between the world we “see” and the world we “interpret,” between reality and perception, objectivity devoid of deep meaning and emotional subjectivity.

People like George Berkeley dedicated their lives to thinking about such distinctions, going as far as to state that reality is built on perception. And, though to us the point was to inspire meaning more than entering a maze of technical terms about reality and human perception, it’s clear that today we need to talk about the need to reenchant the world more than ever, now that every action we do is studied by our digital devices as if they were digital trackers to squeeze our attention and money out of us.

And so perhaps the biggest, most meaningful luxury we can have in our time of convergence of both the digital and physical realms, is to do an outing or to embark on a journey (it can be short, it can be long) in which we are alone with our thoughts if on our own, or just interacting with others without drifting off now and then to look at the screen and let prompts smash our tranquility and push notifications, many of them not even human but automated.

A hut for a young philosopher to think about language

During our family visit to Norway in the summer of 2015, we decided to explore the deepest point of Sognefjord, the country’s longest and deepest fjord. It wasn’t a random choice: there, perched over its most interior point way inland at the end of the Lustrafjord (a branch of the main fjord), sits again a simple cabin built, dismantled, and finally rebuilt recently, of a key 20th-century philosopher.

The place is as magical as it sounds, close to the village of Skjolden and near the largest glacier on the European mainland. No wonder young Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein chose a site in 1913 to build the place nicknamed Østerrike (Little Austria), which he designed and local carpenters built.

And though it was completed in 1914, Wittgenstein didn’t use it fully until the end of World War I. When we visited the area one century later, there was little to remember the hut, for it had fallen into disrepair and was finally dismantled in 1958 (and moved to Bolstadmoen, then rebuilt with some modifications; but that’s another story).

To get to the place, we stayed nearby. I remember walking alone to the hut’s location through a marked trail early in the morning, wondering how to name the smells and plants I was appreciating, and in which language. It made sense, and it freaked me out a little just to think about it.

That is, Wittgenstein’s early work argued that language mirrors reality and that many philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of how words represent the world (he reversed course later in life). I’m really interested in the topic, having lived in a bilingual area of Spain and married outside the Romance-language realm.

Ours isn’t, then, much different from the thinking process that inspired Wittgenstein to write his most influential work, which he sketched while looking at the same trees, accidents, and bodies of water in front of me. However, the impact of nature on us hasn’t always been as cherished. For one, Wittgenstein’s former teacher and mentor at Cambridge, Bertrand Russell, tried to convince him not to go:

“I said it would be lonely, and he said he prostituted his mind talking to intelligent people.”

In quiet seriousness

While serving as an Austro-Hungarian soldier on the Eastern Front, Wittgenstein bought a copy of Tolstoy’s A Confession in Galicia (in present-day Ukraine and Poland), calling it his “gospel” through the war. He described it as the well-worn and annotated text that had saved him, from which he took many insights, such as the notion that many things that can’t be easily said have to be shown.

Perhaps the book resonated so much with him because it showed that anybody (even people as successful as middle-aged Tolstoy, an immensely successful writer who had already published War and Peace and Anna Karenina) can be struck by a paralyzing sense of meaninglessness and nihilism.

But even if Tolstoy’s reading had helped him go through questions about the meaning of life and the limits of reason when violence and brutality appear, Wittgenstein wanted to confront the essentials of existence and write about the building blocks of reality, and his cabin retirement was the place that would force him to try to seek the “name” of things. There was a part of reality that we could make meaningful in a deep, mystical way, and enchantment depended on “faith.”

In a way, his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was also about the limits of reason, and so his book begins from the same place as A Confession: like the Russian writer, he wanted to define what could be thought and said clearly, and what was beyond the simple logic of language: the great ethical and mystical questions seemed to be beyond reason.

“I do believe that it was the right thing for me to come here, thank God. I can’t imagine that I could have worked anywhere as I do here. It’s the quiet and, perhaps, the wonderful scenery; I mean, its quiet seriousness.”

Letter to G. E. Moore, October 1936

He returned many times to the place after the war, revising some of the fragments written there at the beginning. Wittgenstein had taken the first notes of the future Tractatus, the Notes on Logic (1913) and Notes Dictated to Moore (1914) in his cabin near Skjolden; then the war started and he took his notebooks with him, and so his wartime notebooks evolve from technical logical remarks into spiritual reflections with a mystical outlook, partly influenced by Tolstoy’s little book.

Our own ideal cabin

Our trip to Norway and hike up to the place where Wittgenstein’s Little Austria stood took place in late August 2015. Not long after, from 2017 to 2019, a group of enthusiasts restored the hut to its original location and condition, making it a popular pilgrimage.

That’s, again, another story: what brought me to think about our visit there in mid-2015 is the conversation that our visit sparked: it was less sure then, but I just remarked to Kirsten that it was clear, from that place looking down into the fjord surrounded by steep mountains and cascades and with vistas to a tiny village in the distance in front of us, that non-digital contemplation would be a luxury that many would soon crave (Kirsten included my words in the video that she posted on our visit months after, if you’re interested). I’m not glad this is clearly the case today.

The cabin’s placement is perhaps the best description of some thinker’s love-hate relationship with academic and societal norms: they realize they rely on society for even the intricacies of language (which are conventions on how to name things among people), but at the same time declare their autonomy: that’s why the cabin is located 45 meters above the lake of Eidsvatnet, which allowed him to look out the window and see the village in the distance: he wanted quiet and peace or work, as inaccessible as possible while maintaining a visual connection to society.

Wittgenstein’s ethical and aesthetic view of such solitary places amid the might of nature isn’t unique. From solitude and a challenging environment comes raw inspiration, a bit like the mischievous Pan from Knut Hamsun.

But there was another thing that greatly interested me and which I couldn’t benefit from in that trip: observing and exploring the cabin itself, perhaps entering and observing the few furnishings, openings, stove, desk, kitchen, outhouse. When we were there, there was barely the foundation over the bare rock shelf above the lake’s shore.

A solitary shepherd’s hut in a mountain meadow

It’s a seven by eight meters (21 by 24 feet) with an attic and steep-pitched roof to shed winter snow. It had small windows to diminish heat loss during the long winter. Life was simple inside, and the philosopher devised a straightforward system for drawing water from the lake, using a bucket lowered on a wire to hoist it by a pulley.

Our time and circumstances may be very different, but each of us has a way to dwell poetically, turning a shed or cabin into a place of our own. Perhaps each of us has a personal hut waiting to be built, temporary or not, made of shrubs, wood, brick and mortar, or cloth. It can be in a backyard, or at the edge of a nearby forest, or in the wilderness, remote and solitary.

I’ve always been amazed by the beauty of some dry-stone tool sheds and seasonal shepherd huts I’ve stumbled upon when wandering in nature somewhere in Europe, as well as wooden refuges and frontier cabins such as those celebrated in North America. There’s even a replica of Jack London’s cabin from his adventures in the Klondike Gold Rush in Oakland, which I’ve visited a couple of times.

No wonder that some of the passages I’ve most enjoyed reading are about this topic. There’s something about the sound of a distant creek or river, the shimmering of sheep bells at dawn (which I’ve sensed over the years in the Pyrenees, the Picos de Europa, Switzerland, Northern Italy, Germany’s Black Forest) that drives me back home. When in college, I walked along the Camino de Santiago, which took me along Northern Spain from the border with France all the way to Santiago de Compostela.

One early cold morning, when I walked somewhere between the provinces of León and Lugo (possibly before climbing the mountains that lead to O Cebreiro, or a few hours past that point), I passed a humble, tiny stone house at the edge of a meadow closeted by a low stone wall; the chimney was steaming from last night’s fire or one just set during the cold early morning, and the mist of heather pictured the high humidity like a precious painting, animals included.

There was something very ancient in that hut, almost ideal; the mossy granite, the vernacular shape, a small window divided into four tiny squares. From that window, the world must make sense. After so many days walking for long hours, some trees felt special, as did that small hut, probably inhabited only during the summer months when the shepherd kept the flock at a higher altitude for greener pastures.

It was probably a shepherd’s hut, but it could have been a pioneer’s cabin, or a fisherman’s driftwood shack amid the rocky dunes, or a hermit’s cell stripped to the essentials: sleep, fire, peeking at the horizon through a small crack with a warm coffee or tea mug held with both hands for early morning warmup.

A cabin in Nordland

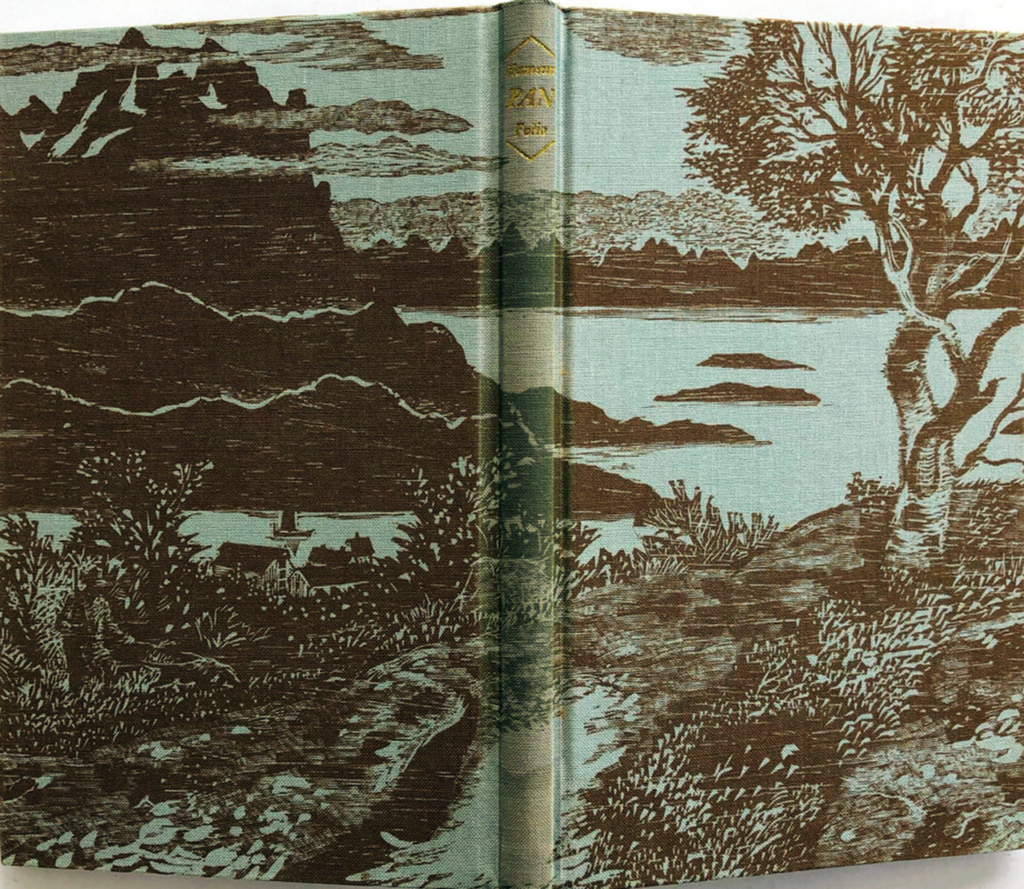

I experience the same feeling when I read about huts at the edge of nature, like the one described by Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun in Pan, a 1894 novel in which the protagonist, former military Thomas Glahn lives a solitary life in the woods of Nordland with his dog, Aesop, a tranquil and simple life away from society, supported by hunting and fishing.

“From the hut where I lived, I could see a confusion of rocks and reefs and islets, and a little of the sea, and a bluish mountain peak or so; behind the hut was the forest. A huge forest it was; and I was glad and grateful beyond measure for the scent of roots and leaves, the thick smell of the fir-sap, that is like the smell of marrow. Only the forest could bring all things to calm within me; my mind was strong and at ease. Day after day I tramped over the wooded hills with Æsop at my side, and asked no more than leave to keep on going there day after day, though most of the ground was covered still with snow and soft slush. I had no company but Æsop; now it is Cora, but at that time it was Æsop, my dog that I afterwards shot.”

Pan, Chapter I, Knut Hamsun, 1894

As described, Glahn’s “hytte” is a simple, single-room wooden dwelling at the edge of a vast forest, the mountains and the sea. The inside is less a conventional home than a cozy, “furry lair,” its walls covered with animal skins and bird’s wings. Not surprisingly, his furnishings are reduced to the bare essentials, mainly a bed, a table, and a long bench. It contains a fireplace for warmth, and at least the one window described.

The bearish veteran lives in the moment, leading a primitive life with his dog, surrounded by the trophies of his hunts and the raw presence of the wild. From his hut, Glahn can see “a confusion of islands and rocks and skerries, a little of the sea, [and] a few blue-tinged peaks.” Just outside there is a big grey boulder, and he feels connected to it to the point of making a bond with it much in the way of pagan nature, in which all elements have a soul of their own:

“Thanks for the lonely night, for the hills, the rush of the darkness and the sea through my heart! Thanks for my life, for my breath, for the boon of being alive to-night; thanks from my heart for these! Hear, east and west, oh, hear. It is the eternal God. This silence murmuring in my ears is the blood of all nature seething; it is God weaving through the world and me. I see a glistening gossamer thread in the light of my fire; I hear a boat rowing across the harbour; the northern lights flare over the heavens to the north. By my immortal soul, I am full of thanks that it is I who am sitting here!”

Pan, Chapter XXIV, Knut Hamsun, 1894

Dreaming of a little cabin

The idea of a primitive survival shelter in inhospitable areas for shepherds and travelers to stay seasonally connects with some of our oldest cultural archetypes, if we consider Carl Jung’s concept of a shared unconscious. The earliest articulation linking primitive shelters to the purest form of vernacular architecture has deep roots, and Vitruvius suggests it in what’s considered the first theoretical compendium of Western architecture (De Architectura, 1st century BCE).

Taking an evolutionary perspective 1,500 years before Renaissance thinkers renewed the interest in the topic, Vitruvius suggested that human habitation evolved from simple shelters made of natural materials common to every locale: branches, leaves, mud, stones, or most commonly their combination, as people sought protection from the elements.

Primitive shelters initially responded to the need for warmth, harsh climates, and safety against wild animals, using readily available materials. Much later, theorists agreed with Vitruvius and considered basic vernacular construction as the beginning of structural construction, or architecture expressing materials and methods honestly, devoid of supplementary ornamentation, and connected to the land to the extent of bringing sense to landscapes.

How many of us delight when we drive through small roads or take a train trip, mesmerized when we observe a tiny cabin or shed at the edge of some rustic property, along with some landmark tree serving as riparian habitat, or perhaps some accident like a boulder, a rolling hill, a sudden slope, or the vegetative signaling of the wicked course of a creek?

For as long as I can remember, I always enjoyed drawing landscapes engraved in my memory since I traveled with my family to rural Spain and I saw humble constructions against the landscape from the back of a yellow Renault 12: rolling hills with higher mountains in the background (the Northern half of Spain is really mountainous), oaks and cypresses, and little huts.

Magic of the one-room hut

If Carl Jung dedicated his life to describing the archetypes in which our soul projects hopes and fears, many of them culturally shared among people, French philosopher Gaston Bachelard did the same with human habitation. In his rooted French-Patois (with his strong Champagne accent, a musical rhythm very distinct from the favored Parisian form), this fatherly figure of mid-twentieth-century philosophy appeared on the French radio to explain how the modern world could be re-enchanted. And, above all, Bachelard was interested in how space isn’t geometric or Cartesian, but intimate, lived, and imagined.

Like Vitruvius almost two millennia before him, Bachelard (white hair and long, white beard —much in the style of the perfect archetype of France’s public grand-père, old Victor Hugo—) evoked the hut as the simplest and most resonating dwelling. Something small, cozy, simple, often a forest or mountain hut, a place of solitude and elemental protection that revolves around one principal element: a fireplace or stove. This space shelters daydreams rather than possessions, and we humans need this type of cosmic intimacy, per Bachelard’s words.

Bachelard’s imagined hut is very similar to the one most of us have in mind but keep undefined, unmaterialized, something “imagined by poets”: the one-room hut, the hut lost in the woods, the refuge that the storm threatens but defies entropy from its corner in the universe, a place from where to peek at the surroundings and contemplate days, seasons go by.

The primitive, humble one-room shelter is perhaps the closest habitation to our soul because we perceive its fragility and isolation. Like creative introspection, it stands exposed to the elements (which can be at once terrifying, liberating, and transformative), yet it gathers the world around it.

“The well-being I feel, seated in front of my fire, while bad weather rages out-of-doors, is entirely animal. A rat in its hole, a rabbit in its burrow, cows in the stable, must all feel the same contentment I feel.”

The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard, 1958

A solitary shepherd planting trees

I’m not sure whether French writer Jean Giono read Bachelard or heard any of his many radio interviews, or whether Bachelard read Giono’s tale and got inspired in return. Giono’s 1953 The Man Who Planted Trees is a four-thousand-word tale that captures the relation between a solitary man in the mountains, the stone cabin he inhabits, and their surroundings.

Narrated by an unnamed traveler that we picture as Giono himself, he wanders through a desolate, barren mountain valley in the southwestern Alpine foothills of Southern France, “as dry as an old bone.” Nothing grows there, and the place seems to have long given up any meaningful relation with mankind.

This changes when the narrator sees what appears to be an object in the distance, perched on one of the slopes, and realizes it is a man with his flock. That’s how he encounters a solitary shepherd named Elzéard Bouffier, who lives quietly with his dog in a small stone house.

“He did not live in a hut but in a real stone house, in which one could clearly see how his own labour had patched the ruin he found there on arrival. Its roof was solid and watertight. The wind that struck it made on its tiles the noise of the sea upon the shore. His household was in order, his dishes washed, his floor swept, his rifle greased; his soup simmered on the fire.”

L’Homme qui plantait des arbres, Jean Giono, 1953

Bouffier is a man who doesn’t say much, but he’s kind and welcomes the visitor, adapting to his presence and inviting him along. He spends his days tending sheep and, especially, carefully selecting seedlings to plant trees, mainly through buying acorns, one by one, across the barren wilderness.

Reenchantment

At first, the traveler thinks little of this rather Quixotic enterprise, which doesn’t seem to make sense in the realm of modern men, for Elzéard Bouffier is planting trees where he considers so, and the land isn’t his: he’s technically working to improve other people’s land, but he doesn’t see it in such a way.

When the traveler returns, he discovers the fruit of Bouffier’s patient daily planting, which has already transformed the valley: springs that had dried up now flow again; villages once abandoned are sought after by new neighbors who want to repopulate the area; birds and other wildlife are returning. The entire locale has turned green, full of new interactions. All because of one humble man’s quiet days up in his stone mountain hut.

But, after revisiting the place several times over the years, the visitor realizes that the transformation he sees isn’t just an ecological act that can be counted in trees, shrubs, restored riparian habitat, water, or wildlife: it’s also a spiritual turnaround.

“For a human being’s character to show truly exceptional qualities, one must have the good fortune to observe his actions for many years. If that action is free of all selfishness, if the idea which guides it is of unparalleled generosity, if it is absolutely certain that it sought no reward anywhere and moreover has left visible marks on the world…”

L’Homme qui plantait des arbres, Jean Giono, 1953

Perhaps nothing today feels more radical than tending to what seems “worthless”: a forgotten hut, a neglected trail, a handful of acorns.

In that patient attention — the shepherd’s planting, the walker’s noticing, the builder’s craft — lies the quiet luxury of our time: to re-enchant the world, one small act of care at a time.