In an age of total surveillance, even our inner lives feel exposed. Yet the world still holds a few communities that have chosen opacity over visibility.

We live in a world of hyper-connection, and there’s nowhere to hide; when there aren’t smartphones around us recording in real time, fitness trackers and other devices are listening, there are limitless inputs that the borg of digital reality can pull from to trace who we want to be and who we really are.

The Find My option in iOS and its Android alternatives can show you, in real time, where your connected devices were last used. In general, your modern car, as well as smartwatches, headphones, smart glasses like the Ray-Ban Meta, “smart” rings, and even blood trackers, are listening.

They will try the wildest workarounds to learn more about you and match your activity with plane tickets, restaurants, gyms, and any other venues you use with your credit card. But you’ve been told you’re freer than anyone else before you in history.

Reality is telling you otherwise, though you’ve already done the Faustian Bargain and are convinced that your supposedly voluntary opt-in (after investing a little fortune to keep your devices and their mandatory recurrent subscription, plus data plans) is going to turn you into a successful Very Online Person. However, there will be a main difference between you and them: you’re using the product and tracking yourself to exhaustion, while true Very Online People are selling you devices and recurring subscriptions while keeping their lives as analog, untracked, and organic as possible.

You, your Nietzschean shadow, and your hologram

Telephone towers and surveillance cameras in public and private spaces aren’t there to make places safer but to erase the possibility of keeping the illusion that we are still owners of our privacy and agency, that we are guardians of our very own destiny, or, as said by poet Willian Ernest Henley, “I am the master of my fate, / I am the captain of my soul.” But, at this point, are we?

German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han believes that we might have lost our agency and ability to develop an individual sense of discovery and awe by buying into the idea that our world requires total positive transparency, so we ought to share our lives online. As a consequence, we’ve surrendered our capacity to wonder once we’ve embraced a culture of constant self-exposure.

But total transparency is making us miserable, he argues, turning the self into a commodity that we try to exploit. So, instead of protecting our inner life, we volunteer it as positive “data,” publishing our emotions, routines, and intimate moments. Instead of living, we’re curating ourselves to the point of exhaustion. Our existential burnout is a feature of our time and the tools we use, not a bug.

A hyper-visible existence isn’t compatible with real freedom and the ability of discovery, once we get rid of anything that isn’t quantifying positively our activity: if there’s no room for privacy, moments of sadness, or doubt, or negativity, or existential conundrums, there’s no need for a rich interiority. There’s no true self.

Also, the pressure to reveal it all destroys mystery and depth—no wonder narratives that allow for human fallibility and contradictions make possible an enchanted existence, and also good literature, and the gift of having talent or sanctity, or even mysterious beauty, or eroticism, as opposed to the in-your-face pornography of maximal transparency.

Total transparency makes reality flat, and the sense of individuality, time, or even distance becomes indistinct and irrelevant.

In praise of romanticism

Big tech won’t agree with writers and thinkers like Dante, Pascal, Goethe (or, philosophically, Byung-Chul Han). Unlike what the pervasive digital borg of positive transparency prescribes for us, such thinkers have made the case over generations: elevated human experiences require privacy, a certain level of opacity, ambiguity, and secrecy, because these are the spaces where mystery and enchantment grow. Imagination expands, desire forms, relationships deepen, and discovery emerges.

With total transparency and a quantified reality, everything is visible, immediate, trackable, and explainable. No wonder people hit the roadblock of exhaustion, or, in Byung-Chul Han’s words, “the inferno of the same.” Nothing surprises us; nothing is hidden long enough to inspire wonder; everything becomes content; and positivity is a commodity whose value trends toward zero.

We shouldn’t be surprised that many young people in societies where the digital world has replaced real-world interaction most efficiently are refusing to have relationships at all, and many are having children on their own, not wanting to “deal” with another person:

Alan Badiou’s In Praise of Love quotes the slogans of the dating service Meetic: “Be in love without falling in love!” Or, “You don’t have to suffer to be in love!” Love undergoes domestication and is positivized as a formula for consumption and comfort. Even the slightest injury must be avoided. Suffering and passion are figures of negativity. On the one hand, they are giving way to enjoyment without negativity. On the other hand, their place has been taken by psychic disturbances such as exhaustion, fatigue, and depression—all of which are to be traced back to the excess of positivity.

Transparenzgesellschaft (The Transparency Society, 2012), Byung Chul Han, English edition by Stanford University Press, 2015, pp. 5-6

Race to total transparency—and obliteration of the self

We think we want total transparency, that the promise of never-ending feeds and never-ending digital entertainment will bring knowledge and happiness. It has created chronic dissatisfaction, a sense of dullness, and depression that sometimes culminates in burnout, especially when overexcited, overdriven, excessive self-reference metastasizes into self-destructive traits.

If you think this perception of our present moment holds some value, you might wonder (as I have) whether there’s a way to return to innocence without losing the parts of our digital footprint we consider valuable.

For one, we can stop having the urge to share everything we consider relevant in our lives online, and stop feeling guilty because we think we may be missing something if we don’t; in fact, this guilt is the by-product of our addictive dependency towards the digital world that is trying to substitute the real one by forcibly become its (ad-friendly) hologram.

The fear of missing out on opportunities if we “don’t get ourselves out there” feeds the internal compulsion to post every opinion, and doing so with fabricated self-assurance by talking fast to the camera.

Paradoxically, hyper-activity, self-optimization, and self-exposure prey on the real self, and since there’s always more to say, more to show, and more to optimize, the individual moves toward exhaustion, loss of agency, loss of desire… As we realize we can’t afford NOT to perform, we cannot relax, cannot fail, cannot simply BE.

The tragedy of our time is that we’re all in this together, but those who understand and can afford the value of disconnecting from the digital rat race. Few people will be able to afford to be really analog.

An important closing line of a sonnet by John Milton

Is there any society outside this hyper-connected reality? For one, we humans have survived and evolved by being good at adapting and transmitting our knowledge through songs and dances full of parables and narratives. We will keep doing so, even when we risk falling into the dullness created by the “Inferno of the same.”

There’s one myth worth preserving, however, and we’re still on time to do so: the myth-reality of the untouched, innocent, and enchanted world in which the last uncontacted tribes of the world reside. Like John Milton’s Sonnet 19, the uncontacted peoples conforming these self-contained civilizations also “serve who only stand and wait.”

By “standing apart” and owning their own time to “wait,” the remaining few uncontacted tribes evoke dignity in being one’s own captain. But, for how long? Can they survive in a hyper-connected world atrophied by quantification and utility?

There’s something that fascinates us about the last uncontacted tribes on earth, a sense of shared responsibility that borders on paternal care, when we think that, by letting them remain outside any contact with modern culture, we keep the dream of the Garden of Eden alive in the collective unconscious.

Now that many use their hyper-connectivity to obsess over conspiracy theories and the Apocalypse, perhaps knowing that there are Edenic spaces untouched by our normative civilization beyond their representation in religious books, literature, and lately pop culture: The Last of Us, Avatar, and Dune are about uncolonized people who are constantly threatened and refuse to fold.

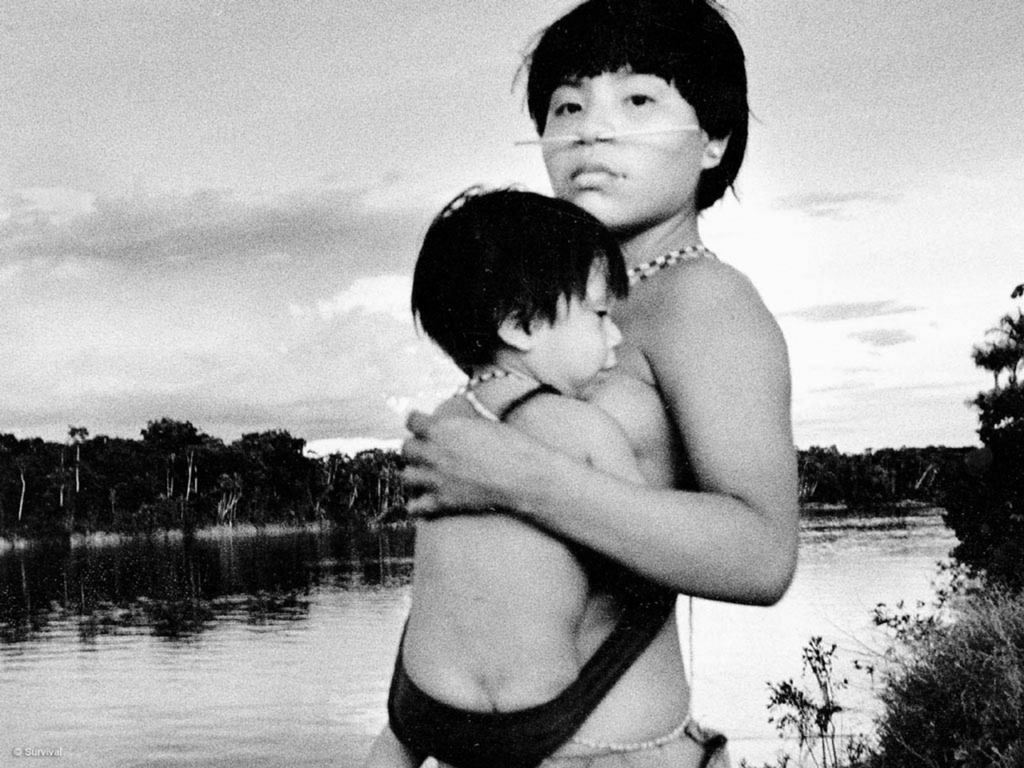

The photograph by Salgado that I imagine

If I had to imagine a photograph by Sebastião Salgado that would symbolize both the fragility and the hope of what the uncontacted tribes represent to a world in acceleration, this picture could in fact have been taken by the greatest photographer born in Brazil—committed to both the enchantment of nature and the possibility of redemption for our species, after all “the salt of the Earth” (a Biblical reference, and the title chosen by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado for their retrospective documentary on the photographer—.

This picture by the Brazilian master of black-and-white photography and author of books such as Genesis (depicting the beauty of re-enchanted landscapes on Earth and the beauty of people unchanged by our acceleration) would be at once masterful and straightforward. Perhaps one single figure sliding across a river in the foggy early morning in the depths of the Amazon.

Such an image might suggest that there’s a small but still open possibility that the few uncontacted tribes in the Amazon basin, Asia, and the Pacific will “stand and wait,” as in the poem, to keep evoking the dignity and stillness of an existence that doesn’t depend on quantified performance.

Such a picture by Salgado would be the anti-Instagram picture, seeking meaning rather than engagement, and symbolically fighting for the right to opacity rather than the mandate of transparency and hyper-connection at all costs.

I’m also glad that this picture doesn’t exist. It means we didn’t try to protect uncontacted peoples by contacting them. That’s why Sebastião Salgado never took it, but the hollow space left by the inexistence of this picture is perhaps Salgado’s greatest legacy.

The Amazon we shouldn’t try to get to know better

Survival International’s latest report suggests that this illegibility—this right to opacity—is collapsing under satellite eyes, armed loggers, and deforestation fueled by cattle herding and intensive agriculture.

According to Survival International’s late October 2025 report, half of the uncontacted tribes “will be wiped out within 10 years unless urgent action is taken.” The right to opacity isn’t only collapsing for us at the epicenter of modernity, but also for those who voluntarily never engaged with the outside world.

Paradoxically, to be protected, the 196 groups of uncontacted peoples living in 10 countries across the world are being heavily surveilled from a cautious distance, mapped by drones, cornered by roads, overheard by GPS-enabled machinery, and tracked to state their movable boundaries. Albeit this is surveillance as triage, not intrusion.

The Amazon region is home to most of these peoples, with 187 groups (127 of which are within Brazil’s borders).

And yes, our always-on moment, in which people are incentivized to record their outlandish exploits, no matter how far or dangerous, influencers are a significant part of the problem.

Information and industry advance rapidly, but any actual contact between members of uncontacted peoples and people from the outside could trigger and even faster and more consequential risk: that of epidemics, which already transformed the Western Hemisphere right after the arrival of Europeans with their guns, germs, and steel, not necessarily in the order stated by Jared Diamond on the title of his 1997 book.

Social media at its worst

“Industrial activity such as logging, agribusiness, mining, and road-building destroys forests and Indigenous territories, pollutes rivers, destroys homes, and facilitates colonization by settlers. The result? Malnutrition, poisoning, starvation, destruction of communities — even when there is no direct contact. A single missionary, oil worker, or logger carrying a common disease could wipe out a population. Violent attacks, including killing, are also common.”

In Brazil, incentives from China to accelerate the production of beef and soy will speed the risk of contagion; in Peruvian and Colombian Amazon, isolated groups are being pushed deeper into the forest; in the Andaman Islands the Sentinelese are wary of any visitor coming by boat after previous contacts brought disease to the island and a missionary got killed for trying to get too close to them.

According to the report, logging, mining, and oil and gas drilling are the most impactful threats, affecting potentially 96% of such groups. However, they aren’t the only risk: 38 uncontacted tribes are being forcibly “civilized” by government-endorsed development projects, whereas “one in six uncontacted peoples are threatened by missionaries trying to convert them.”

As perceived rising threads, this one caught my attention:

“Social media influencers who seek to make “first contact” for content they can monetize through subscribers and advertising; missionaries, bankrolled by multi-million-dollar evangelical organizations, use the latest technology to find and track uncontacted tribes to convert them to Christianity; violent criminal gangs grow and traffic drugs or run illegal mining operations deep in the Amazon.”

Life beyond visibility

We’re past the moment of self-righteousness, and everything is in the open, showing the glorious shortsightedness.

These are not theoretical risks but the sleepwalk into a symbolic civilizational narrowing, as we lose the last human communities that never engaged in the idea of progress and its latest iteration: positive, unescapable transparency, which translates into surveillance and the impossibility of unquantified freedom, a life of chosen opacity, myth, silence, and full autonomy as their way of being.

Perhaps this is why the imagery of Sebastião Salgado feels more urgent now, after his passing, than at any other moment. His photographs captured not just people but the possibility of another tempo, another definition of freedom. Today, in his absence, the question lingers heavier:

If the last uncontacted tribes disappear, who will remain to show us that a life beyond visibility is still possible?