On the vanishing patience for depth, and the quiet rebellion of those who still read.

Loosely paraphrasing Mark Twain, the report of the death of long-form reading is being greatly exaggerated. There are signs of stress on our attention span, however.

If I were to make a personal case for why reading high-quality long-form content is the best investment one can make for the future, I’d say that reading essential information is the most effective way to gain in-depth knowledge, probably only second to learning by doing.

Say, if you want to know about the experience of sailing in the late nineteenth century changing world, you can either read books like Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim or get to sail the distant seas working on a merchant ship with an international, underpaid crew, for months. Imagine how lucky those who embark on both endeavors during their formative years are (if I were to tell this to my older daughter, an aloof reader, she’d probably tell me that Joseph Conrad is overrated and for guys; I’d say in my defense that I must be a very conventional male on these matters).

To those who rightfully don’t like other people to tell them what’s best for them or what to read and want to improve in life by forging ahead according to their own instinct, a process of debunking conjectures through the good-ol’ trial-and-error method, which Karl Popper called “falsifiability.”

Sensorial hangover vs. nurturing “flow”

Let’s propose a test anybody can make: One has only to analyze how they feel after a session of binge watching a bunch of algorithm-fed random short videos (accompained by a force-fed long list of products and services succintly advertised within the commodified “content”), vs. the reflective and “flow” state, more related to zen than to sensorial exhaustion, felt every time they finish reading a worthy long article, a book, a thoughtful essay, a timeless movie, a mind-expanding video or documentary.

The first state (binge watching random content) doesn’t add more than the defeated appetite of the dopamine addict in search of the ultimate fix that will cure all anxieties and will never come, as it’s a mirage as elusive as the fake oasis people lost in the desert see on the horizon before losing consciousness for good. By contrast, the second state is akin to enlightenment, and after processing something that we feel was meaningful, we feel strangely tired yet replenished at once, as if we had spent time with an intelligent, faithful friend who genuinely wants us well and doesn’t deceive us with commodified information noise.

This second “flow” state is never the same as watching something that feels like background white noise or skimming AI-generated summaries that impoverish any experience, but more like having a long conversation where meaning unfolds slowly, often through nuance, rhythm, silence, or the experience and opinions of others (in our time or in the past, alive or long dead).

Often, depth requires duration, because to understand something—or someone—one needs to embark on the impossible task of reaching beyond the event horizon and overcoming the clichés of initial comprehension. It demands patience, but the rewards (if not truly tangible) are life-changing, allowing us to acquire perspective and deep knowledge, just like a quiet mental digestion that creates understanding rather than mere awareness.

Does long always equal nuance and depth?

That said, there’s a contrarian take to the fact that depth requires long form. I’ll call it the fallacy of “long equals deep”: length alone doesn’t guarantee depth, let alone the timeless quality of information and art artifacts worth exploring. As the online world we’ve built lowers the entry barrier to create very long podcasts, Twitch livestreams, etc., there’s an endless proliferation of niche pieces of information filled with commentary filler, which many people tolerate because they can’t get enough of their favorite influencers. It feels as if people, feeling the dreadful alienation of a meaningless and solitary contemporary life, opt to substitute real channels for nurturing themselves and overcoming the lack of meaning they feel by tuning in to the lives (and live streams, endless podcasts) of others.

When we “consume” endless trivial content, we may be training “patience” without training discernment. Perhaps the most resilient individuals, talented at navigating content, become so adept at separating signal from noise that they can literally discern the value of any shallow, clickbait piece of information, learning to think critically in any information overload environment. But such “survivors” are a minority, and most people succumb to the reality-blurring blurb of the content snack, now poised to accelerate even more if AI-generated TikTok copycats get popular among endless-feed junkies.

There was a time when rubbishy content was associated with insufferable dread to avoid at all costs. Some content today can remind people who’ve lived in undemocratic countries of the marathon speeches of their leaders—hours of inconsequential talking, leaving listeners to sift through repetition and filler for the occasional nugget of insight. Just as no one would mistake Fidel Castro’s speeches for concise brevity, the sheer length of modern digital slop doesn’t guarantee depth—it tests patience more than understanding.

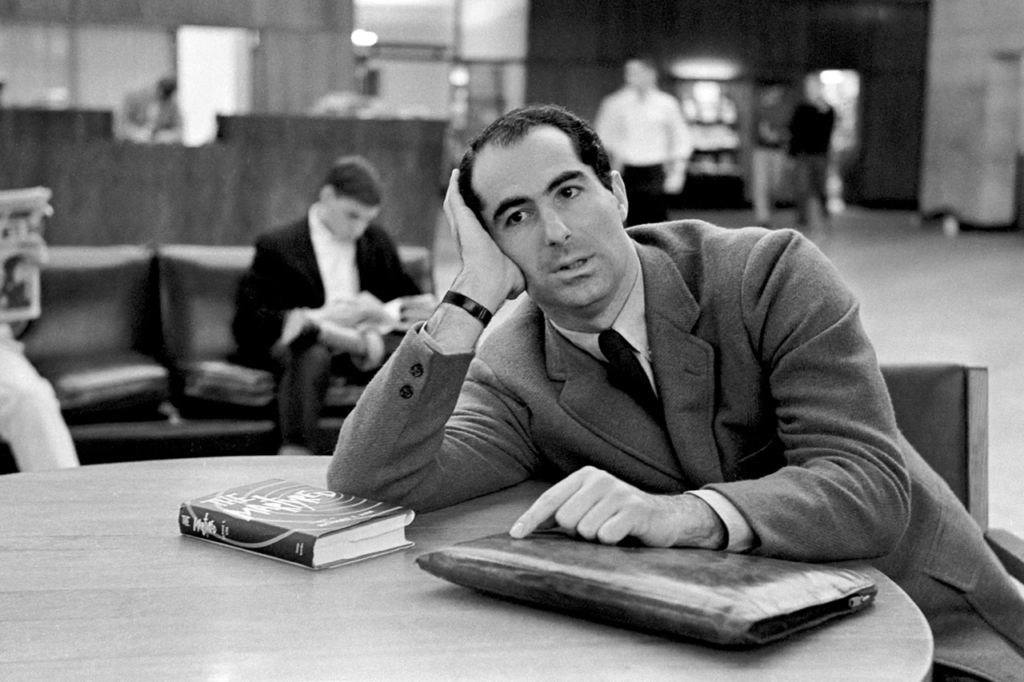

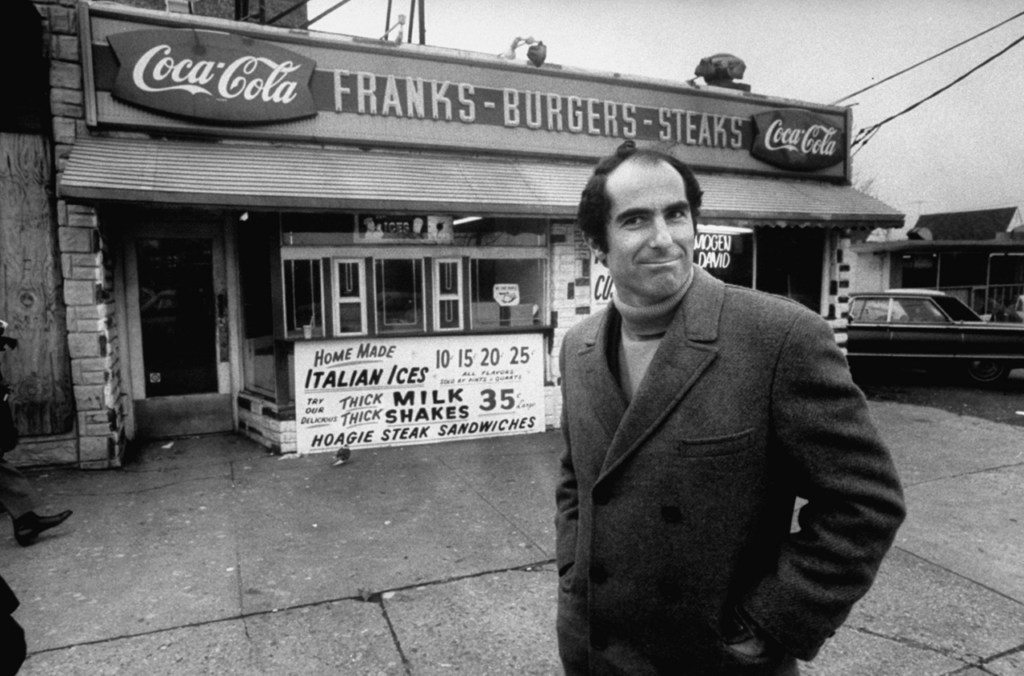

By contrast, books are very different: the insights we get from good literature feel like life experience, and we can indeed experience many lives by reading books and watching good movies. For example, all I know about Newark comes from Philip Roth. Spending hours with Roth isn’t a test of patience for its own sake—it’s an invitation into a mind, a city, a time. Through his meticulous attention to Newark’s streets, neighborhoods, and social fabric, you don’t just hear about the city; you live its complexities, understand its tensions, and feel the human stakes behind its history. This is the difference between being subjected to length and learning from it—between listening to endless chatter and absorbing insight that reshapes how you see the world.

Getting to know a place in depth through a reliable host

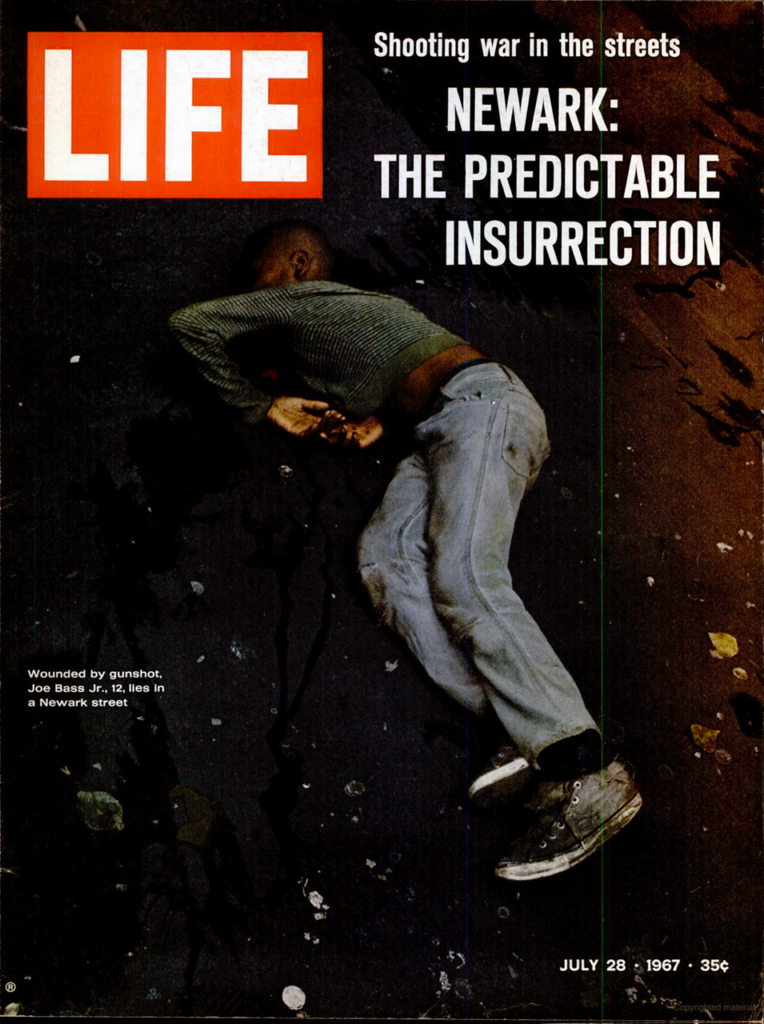

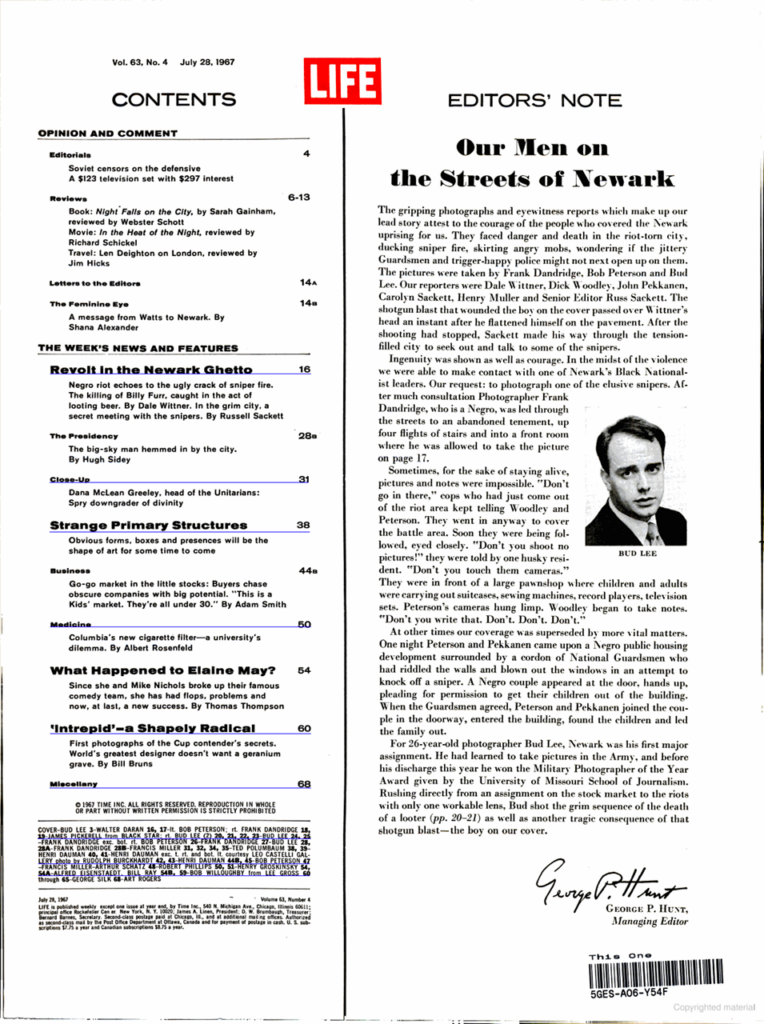

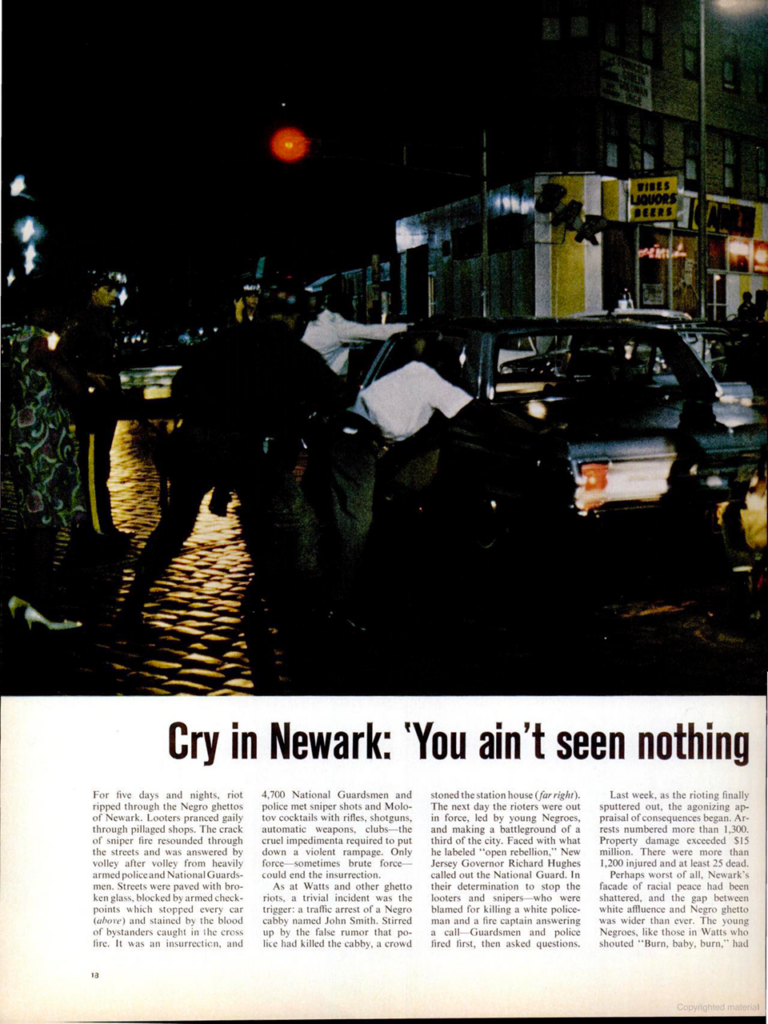

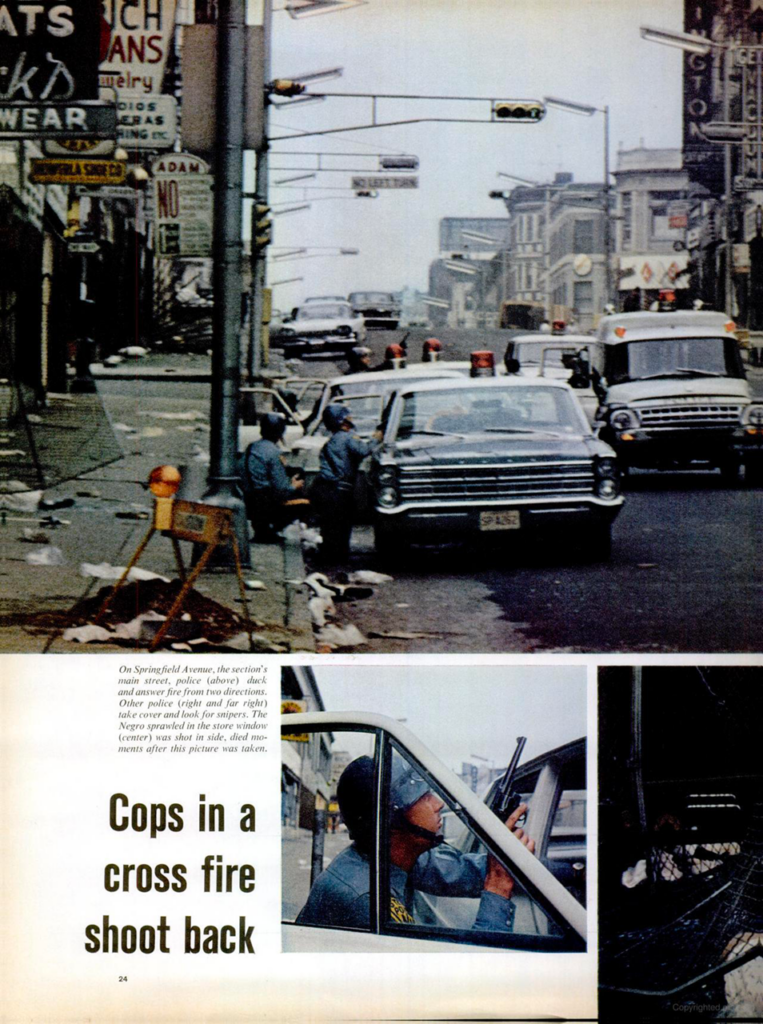

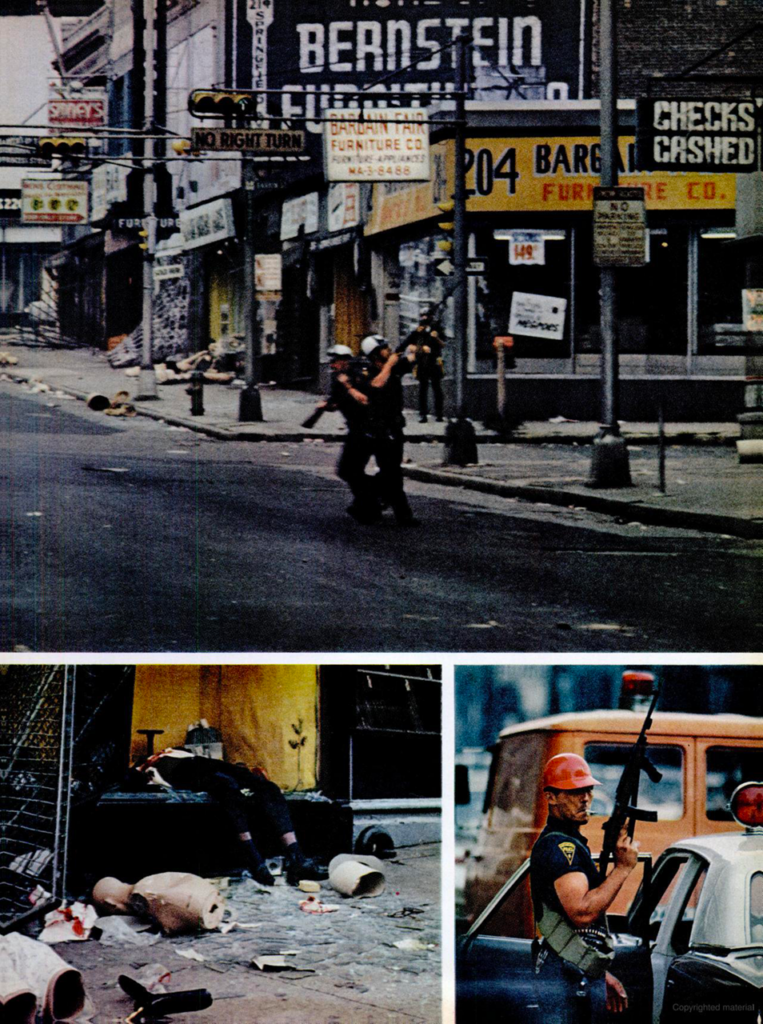

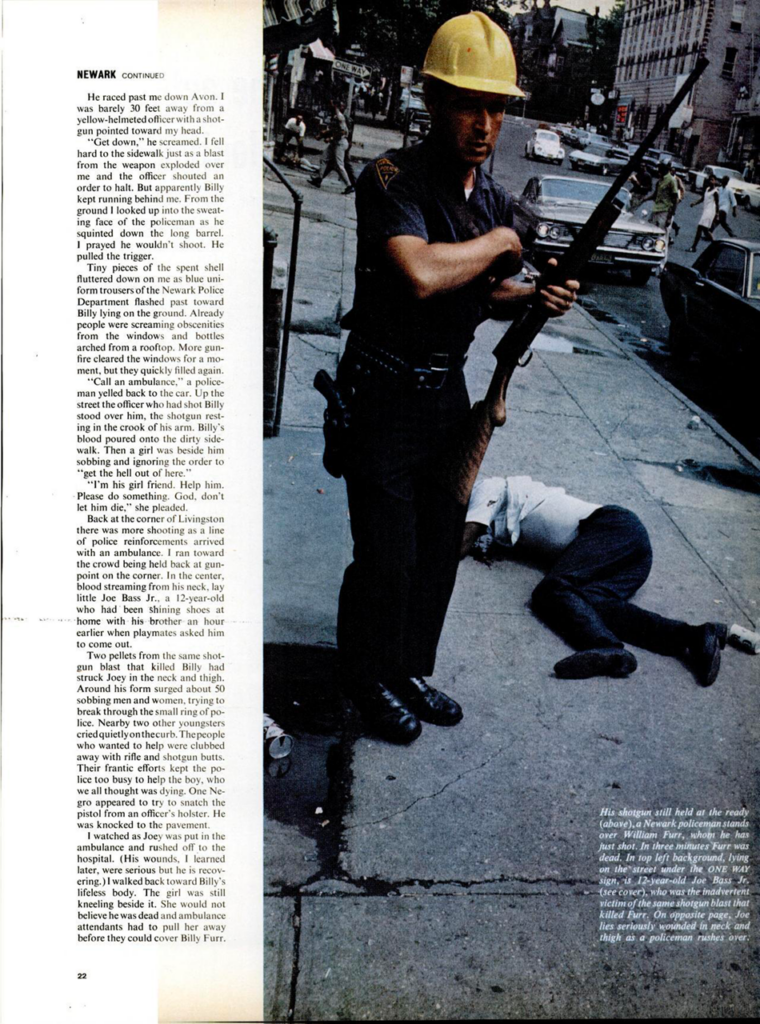

American Pastoral impacted me for many reasons, but what I really appreciated was the cinematic, profound, and tender portrait of post-WWII Newark that vanished over the decades, accelerating its decline after the Civil Rights riots of the sixties. We attend first-hand the excesses of radicalized people who fall for cultish ideologies in the character of Meredith, “Merry,” who, by planting a bomb and killing a bystander, destroys much more than their parents’ sense of the world.

As it has happened many times to me, checking the film adaptation was a big disappointment, for both genres are very different, and it’s very difficult to capture the aura, as described by the narrator in first person, of awe and invincibility of The Swede—the blonde, perfect All-American Jewish kid from the book that struggles as an adult to transform his early potential into the manifested destiny of the American Dream.

The literary alter ego chosen by Roth for the narrator of American Pastoral, a mature man that still remembered the impression that The Swede had had in him, isn’t the compulsive onanist Alexander Portnoy from Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) nor the introspective, sensual David Kepesh (used by the author in the titles The Breast, The Professor of Desire, and The Dying Animal) but Nathan Zuckerman, perhaps the most humane of all of the author’s alter egos, the least charicaturesque of them all.

As a doppelgänger, Zuckerman is reliable both narratively and psychologically. So I loved to hear from him about the complexities of American society in a particular place and time: urban and rural New Jersey before and after the shock of the Civil Rights riots—a period of violence and property damage that prompted the deployment of the National Guard and the subsequent accelerated flight, and a long period of decay.

Through the book, we observe the working-class families of Jewish immigrants and the small shopkeepers specializing in the goods of a different era, such as quality leather glove-making, and see how The Swede, called for greatness by nature, dating up and marries an Irish Catholic local beauty queen—Miss New Jersey—, moving to a WASPy suburb of rolling hills in a fictional New Jersey small town (apparently the perfect perk for the perfect American life).

All the things we miss when we think summarizing “content” is good enough

As it happens with the nuanced stories of Philip Roth, the idylic, neatly manicured rural setting of rolling hills and white picket fences won’t shield the Swede from social, political, and familial breakdown, especially as his only child, the perfect little girl, grows to become a political extemist and, ultimately, a domestic terrorist much in the fashion of the 1960s political upheaval, shatering the Swede’s idealized life.

What I always liked about the book is how it describes a place, a country, a state of mind, the hopes of different generations of Americans, the dream of cultural assimilation into the mainstream of American Jews, and the contradictions between fitting in and preserving a distinctive character and authenticity. But, above all, the provocative, unsettling discomfort it creates in its readers. Since the beginning, Philip Roth refused to become a niche, tamed Jewish writer idealizing the achievements of this demographic within America, and described himself as an American writer at large.

Roth chose to live in public discomfort, refusing to idealize the Jewish experience in suburban or American life, instead exposing the contradictions, anxieties, and moral ambiguities within it. In American Pastoral and his other works, Roth portrays Jewish characters not as paragons of virtue or assimilation but as complex, flawed, and deeply human individuals, often caught between cultural expectations and the turbulence of modern society. The Swede, for example, is outwardly successful and admired, yet Roth does not shy away from showing his insecurities, ethical struggles, and vulnerability to forces beyond his control.

He was also interested in exposing the con and highlighting the tensions within Jewish identity: sexual depravity, anti-Semitism, class anxieties, generational rebellion… He was ready to challenge readers by confronting complexities that many considered counterproductive and politically incorrect. But, fortunately, he didn’t give a dam about this, stripping away the comforting myths of moral clarity and social progress, and opening the wounds to the messy lives and painful truths of people’s little everyday miseries.

Where are the reliable voices of today?

As someone curious about the world, I thank him for this and his refusal to conform to and play along with the dominant trends of every era. It may be that I’ve reached middle age, or perhaps that our older daughter has already left the family nest to attend college: to put it mildly, I’ve been struggling lately with the current lack of distinctive, uncomfortable intellectuals capable of making a constructive impact with their work in the many challenges of today.

I’d like to read people like Christopher Hitchens on the American political drift of the last years. I would appreciate, and really pay attention, to what somebody Philip Roth would have to say about the current uncomfortable need of many American Jews to remain aligned with Israel’s untenable position and self-delusion regarding Gaza and the West Bank—the suffering, the gaslighting, the self-censorship, the connivence with the current Administration to silence any voice that doesn’t conform to the sole narrative there is.

There was a time when public people of a certain intellectual stature were uncomfortable for everybody during crucial times, because their opinion and work weren’t the clichés, the easy ones. Old provocateurs would write the books, the essays, the articles, attend the debates and interviews, not planning to massage them, but often the opposite. They would shock, and they’d sometimes be willing to feel publicly alone, ostracized, or worse.

By contrast, today we’re supposed to think that the most subversive and nurturing thing that happened to American journalism lately is Bari Weiss’s The Free Press, which self-defines as “honest journalism” writing “stories that are ignored or misrepresented by legacy media” and fighting (curiously, like the current Administration) woke ideology. If anything, The Free Press’s most significant achievement is to manage to convince many well-positioned and wealthy urban (former) centrists and conservatives that having retrograde and fanatically pro-Israel positions is subversive and very anti-establishment. For that, Bari Weiss’s media venture (launched as Common Sense on Substack in 2021, and later rebranded) was just acquired by Paramount, parent of CBS News, at David Ellison’s direction on the matter.

We’re encouraged to believe that all is well—that new ventures like The Free Press represent a freer, more independent alternative to legacy media, unburdened by special interests or internal conflicts. Changes for the better? Show me the Christopher Hitchens types, and I’ll gladly change my opinion on this. However, what I see is not better and more independent journalism, but a great deal of cosplaying and petty grifting.

On the other side of the spectrum, the names breaking through are also converging with Fidel Castro speeches: very long, largely inconsequential, cliche-driven. It is no wonder that today’s public commentators lack the reach, long-lasting influence, and moral authority of the intellectuals of yesteryear. Instead, today’s commentators can access real-time tools that allow them to perform A/B tests to determine which message works best with their target audience. Strategies like monetizing outrage and leveraging rank-and-file fanatic support have supplanted any editorial scruples.

People falling for information babysitters

This trend coincides with a palpable decline in the influence of old-school journalism and long-form information (books, TV, movies, etc.), a decrease in society’s overall attention span, and the potential rise of AI-generated slop, which could amplify this trend.

But not all is bad in the monster repository of the world’s information we’ve built: we can also find interesting nuggets of almost anything imaginable. Consider, for example, this 2004 TV interview conceded by Philip Roth, in which he foreshadows:

“I don’t think in twenty or twenty-five years anyone will read these things at all. I think it’s inevitable. I think there are other things for people to do, other ways for them to be occupied, other ways for them to be imaginatively engaged, that I think are probably far more compelling than the novel, so I think the novel’s day has come and gone.”

I’ve read many articles lately about the many people recognizing that they don’t read any fiction at all, especially if it’s long form, because they don’t see any direct utility in it—they’re too busy with the unending podcast episodes and livestreams, which they often listen and watch at once on platforms such as YouTube, Spotify and Twitch.

Recent studies note that fewer people are reading for fun, perhaps because it takes energy, effort, discipline and focus to sit for long periods of time with a book, and the trend is especially concerning among the newer college grad cohorts.

Not everyone is about to fall for content slop

After reading articles commenting on such studies, I’d buy this narrative without hesitation, especially considering what I observe in my middle daughter and younger son. But my older daughter says she doesn’t buy this. Not long ago, I discussed this topic of concern for all of us with her, in which she adopted the contrarian position I also liked to have when I was her age. We were discussing smartphones, attention spans, and the numerous articles and studies that argue we read less fiction and non-fiction than before, and our reading is somehow shorter, more casual, and less in-depth.

This trend doesn’t seem to apply to reading long-form stories, but it is also present in other cultural artifacts, such as video, audio, or even video games. Namely, we, as people, can hardly keep up with traditional, high-production video content, such as movies and documentaries, prioritizing lower units of information that are, in memetics terms, “memeified,” or optimized for engagement. The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future (2016) is a pre-pandemic, pre-TikTok boom essay by Wired founding editor Kevin Kelly that explains the trends in play that are shaping our reality. The book is aging quite well.

Yet many exceptions refute this thesis, namely the reality lived by young adults like my older daughter, a college freshman: she doesn’t only read tons of long form but often does it in the small screen of her phone for long chunks at a time, not getting distracted by the instant gratification call of all the things she could watch and click on the same screen if she were to decide so at every instant. So, at least some people are capable of pulling it off and thriving in this world of engagement and AI slop. Perhaps—she says—a part of what’s happening is that old legacy content (books, movies, old-school journalism) is not as interesting as many think, if compared to new forms of contemporary long form.

There are, for example, novelists speaking to their younger audiences about the world they experience, and people are reading their books. There are even writers, like Gabrielle Zevin, capable of crafting good literature out of a topic that many would consider off-topic for serious novels: the world of gamers and video game creators.

So, in a way, having witty teenagers and young adults around can give one access to narratives that are a bit more nuanced and less pessimistic about the future. Overall, many kids are alright. However, I can’t assess whether they are the majority or, on the contrary, a bunch of survivors amid the advance of The Big Slop.

Complaining about youth’s superficiality isn’t new

To illustrate this, many intellectuals of the Ancient Classic World complained about the inability to focus and short attention span of the younger generations, among them Hesiod, Socrates, Plato, Aristophanes, Juvenal, and Quintilian (that is, from the 8th-7th century BCE to the 1st-2nd century CE). The complaint isn’t new.

However, one has to concede that something happened since the proliferation of modern mass media and propaganda at the beginning of the twentieth century, as explained by authors like Walter Benjamin (non-fiction) and George Orwell (non-fiction and fiction, both largely dystopian and pessimistic about the visible trends back then, now fully materialized). Now we have entered a new acceleration (AI) within another acceleration (the internet) of this process.

Consider, for example, this 1984 excerpt that someone just mentioned in the slop repository of Substacks:

“There was a whole chain of separate departments dealing with proletarian literature, music, drama, and entertainment generally. Here were produced rubbishy newspapers, containing almost nothing except sport, crime, and astrology, sensational five-cent novelettes, films oozing with sex, and sentimental songs which were composed entirely by mechanical means on a special kind of kaleidoscope known as a versificator.”

Was it much different in the mid-1990s, back when the internet was still in its early stages and I was a college freshman, just like my daughter is now? It’s not that we didn’t have pop culture distractions back then. To me, going to college wasn’t probably as pivotal, as I stayed at home and didn’t leave my area to attend University, as is often the case in Europe. That said, people leave their upbringing environment and begin to spend more time with self-selected (and self-selective) people that inhabit other geographical and socio-economic realities, and the world seems to expand suddenly.

Back then, early GSM mobile telephones could only call and text, and I don’t think I owned one yet, but they were becoming more popular and changing many things. We would call each other at home by landline telephone, and many times we had to deal with things such as being late or not showing up at places, with no way to prevent other people from showing up and wasting their time. There’s something romantic from that period, and I believe—but can’t prove—we had more patience and didn’t mind leaving things to serendipity. Being somewhere contemplating wasn’t wasting one’s time, and the hyper-utilitarian need to be “on” all the time had not eaten the world yet.

The depth I benefited from in pop culture (not in class) as a college freshman

Pop culture distractions abounded, however, both in analogical and digital forms. I enjoyed playing a few video games, including Quake, back then, as well as strategy titles such as the Civilization and Caesar sagas. My brother and I had many friends interested in music, comic books, and all sorts of magazines and pseudo-fanzines, so there were those, too.

But I also remember how easy it was for me to drop the promise of any distraction when I felt that a book was worth diving into. In my first year of college, I often found myself missing classes to visit the cafeteria or the library, where I would read a mix of New Journalism titles and popular culture bestsellers of the time. That first college year, I read Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose and Patrick Süskind’s Perfume, and my perception of the world was never the same afterward. Things of serendipity: I lived with Kirsten and the kids early on in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter, on one street used by the director in charge of the movie adaptation to recreate 18th-century Paris.

I learned many things from Medieval analytical monks and 18th-century city stench, and I’ll always be thankful to Eco and Süskind for that. I also read a lot of long form pseudo-literature, like Spanish pop literature writer Alberto Vázquez-Figueroa (I remember especially two books, one set in the Sahara, and another deep in the Amazon basin, and I learned many things about North Africa’s historic struggles and about the fascinating story and importance of natural rubber from the Amazon during the early twentieth century thanks to this author, whom many cultured people looked down to, which I didn’t care).

Interestingly, Vázquez-Figueroa’s novels have sold over 25 million copies worldwide, and the author is also an inventor and industrialist (a native of the Canary Islands, he owns a desalination company that uses a method of water desalination that he invented).

Now, imagine for a moment that the first-year students of today are not as fortunate. I really hope that The Great Slop doesn’t prevent them from finding their own life-changing long-form stories, whether they are considered high or pop culture, for both worlds collide, and besides, such labels are often sanctioned by sanctimonious, highly biased, and prejudiced literary critics.