You don’t live in a vacuum. You live among echoes — digital, cultural, ancestral — shaping the melody of your so-called individuality.

Philosophy can be a bore, but sometimes it helps us see things the way a good song, a poem, a story, or a stand-up comedy show can. Consider the bore and “unreadable” musings of the likes of Martin Heidegger, pardon my French.

Despite his cryptic, “philosophy for philosophers” take, Heidegger expresses rather clearly one thing that no one else pointed out as well as he did before or after: our co-dependence. We are beings embedded in the world; we live “within” it and depend on a context and a set of realities and subjectivities. We weren’t born or live in a vacuum, for our circumstances depend on many factors.

Perhaps sometime in the future somebody will be born in a zero-gravity, planetless environment like the International Space Station (free from actual gravity and the gravitas of culture and upbringing), but until that moment arrives, all individuals of our species deal with a lot of contingencies since the moment they’re conceived, from epigenetics to what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called with wonky academic words such as “habitus”: our context has an influence upon us.

Much more than consumption recipients

It’s not that contemporary society isn’t trying to have us live in a vacuum, shaping us as passive recipients to be programmed for consumption. The extreme metaphor of this trend can be seen in the human farms of The Matrix, as well as in books and plays that reacted against war, pain, and alienation during the World Wars period.

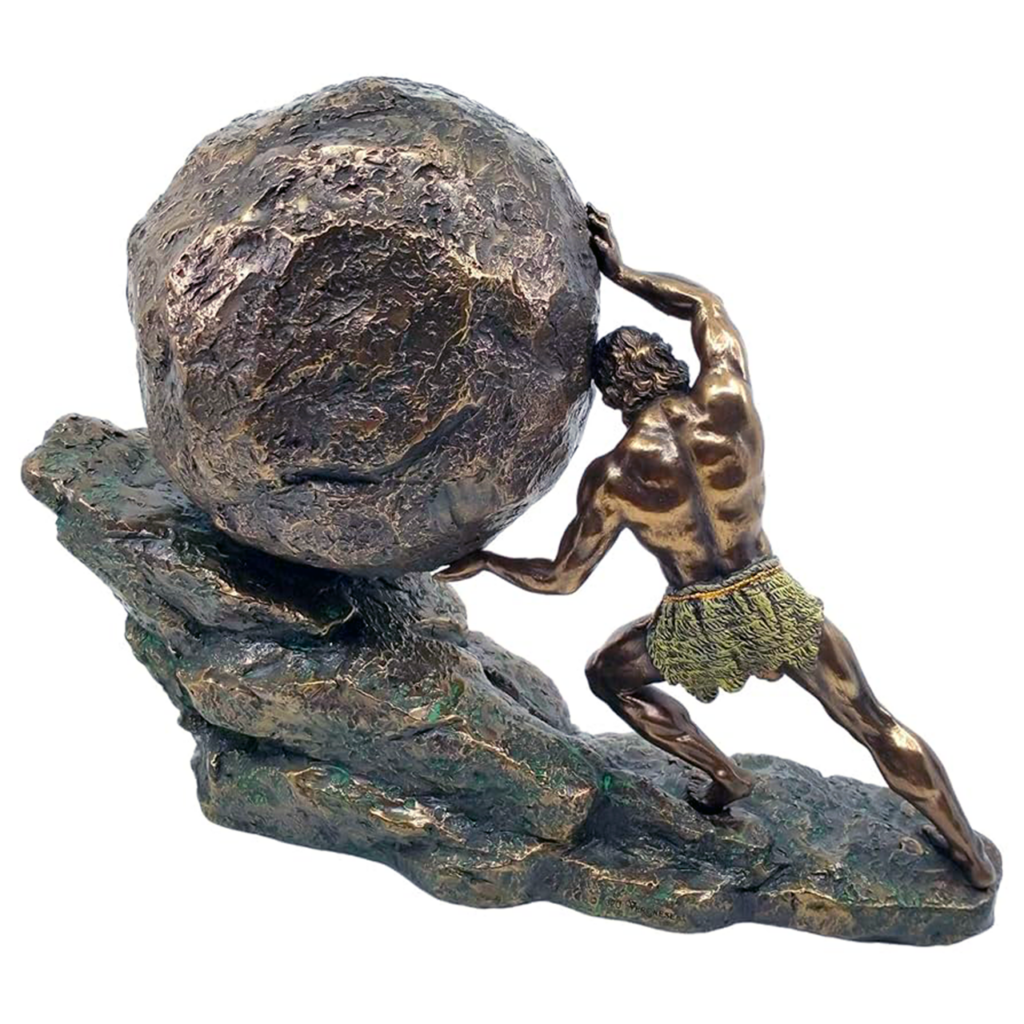

When the world starts to feel scripted, absurdism reappears—not as artifice, but as diagnosis. Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus is the theorization of his novella The Stranger:

“In a universe that is suddenly deprived of illusions and of light, man feels a stranger… This divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, truly constitutes the feeling of Absurdity.”

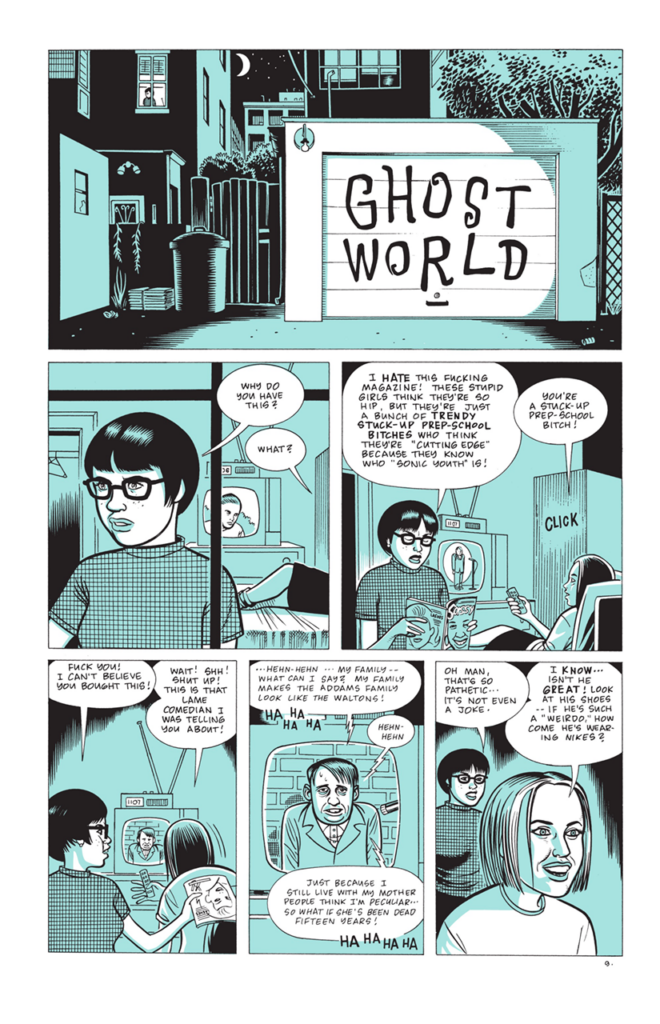

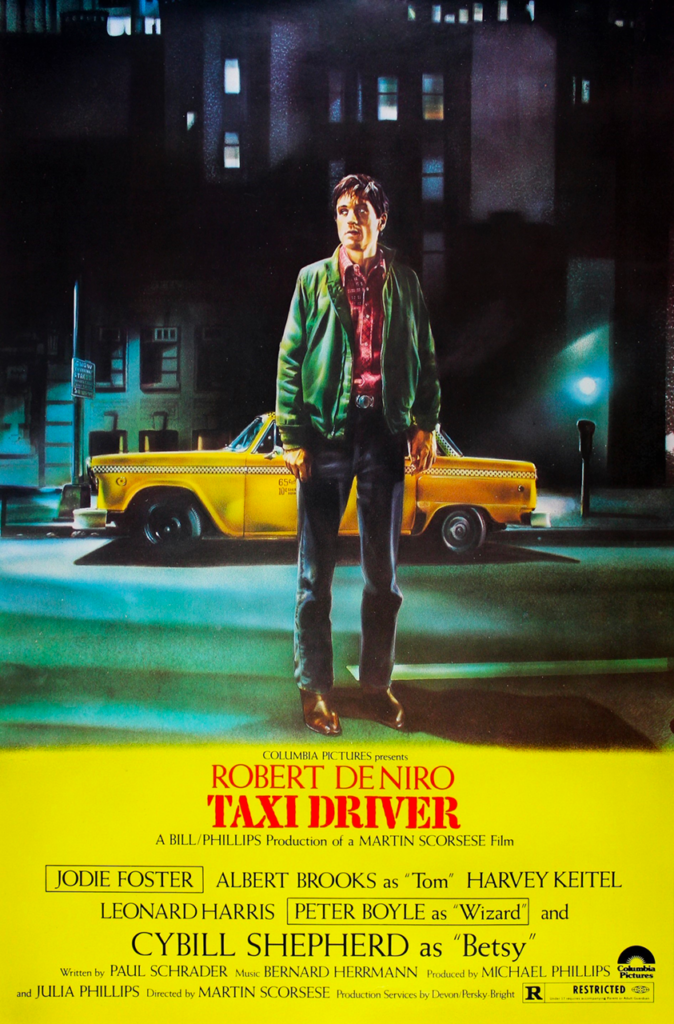

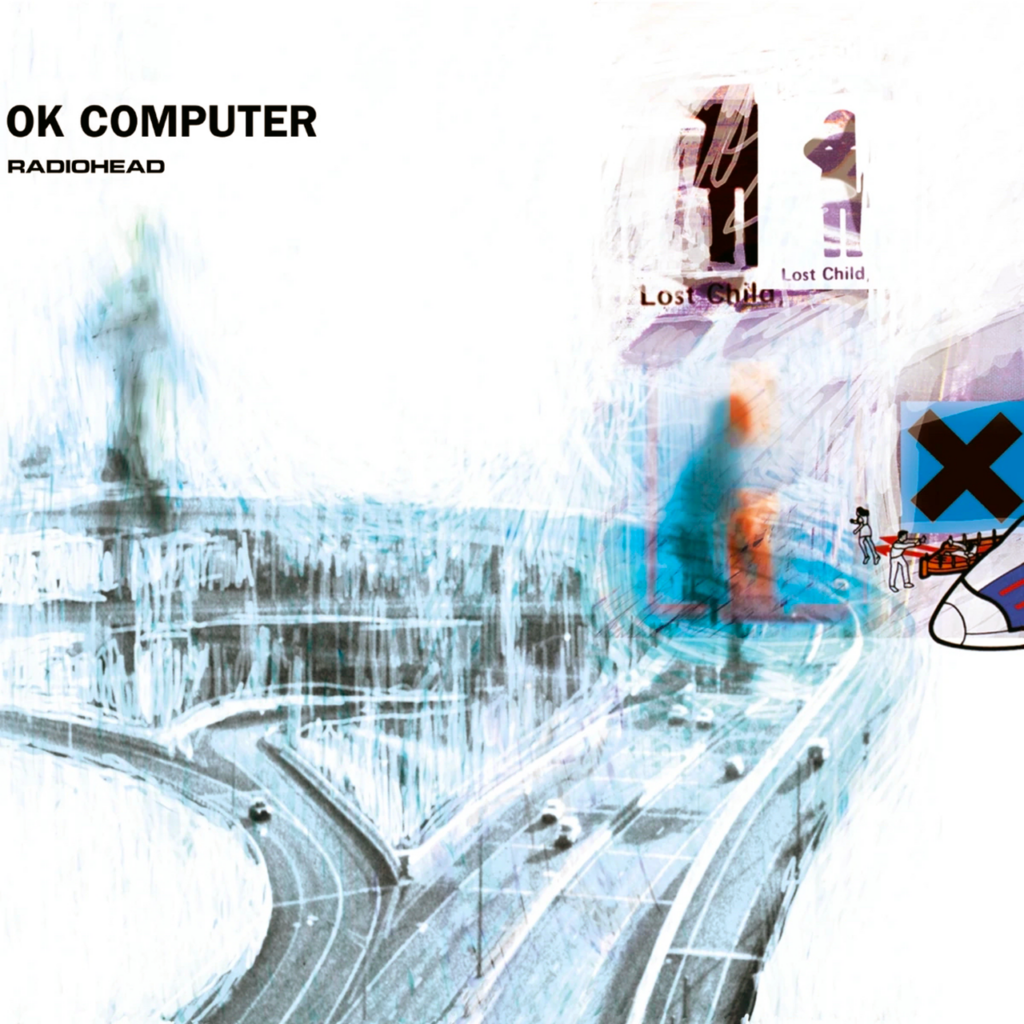

To those a bit lost with my cultural references. When I talk about The Stranger, you can think of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver, and voilà, we’re on the same page. If you want to put a soundtrack to it, think Pink Floyd’s 1979 The Wall (to those of you mature enough), or Radiohead’s 1997 OK Computer album; in comic book terms, we could be talking about Daniel Clowes’ 1997 Ghost World. Like The Stranger, each of these references represents people cursed for being lucid, sleepwalking in a meaningless world.

And, like Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro (the treatment of light and shade in drawing and painting during the European Baroque era), well-understood, balanced individualism can bring light upon us, but also the lifeless darkness of ultimate alienation: many powerful forces want us docile, divided, numb, narcotized, and subversive art feels like an antidote today, for it reminds people it’s their intellectual and moral duty to be self-conscious about it.

From one-person orchestras to one-person demonstrations

According to today’s system of fragmentary news and social media that the majority of us rely on to get a pulse of what’s going on, if we were to trust the main societal trends on how we should engage in action to help transform the things, big and small, that we want to change in society, we would be told that we should avoid any controversial take, or collective action, or any performative, demonstrative act.

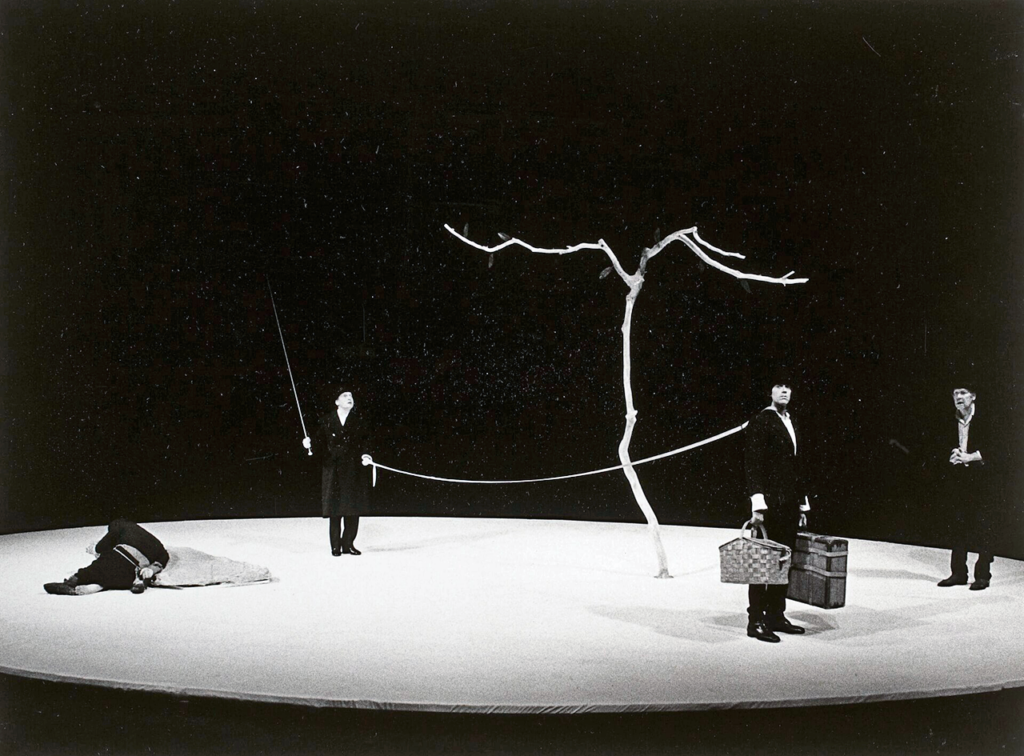

It’s today’s version of the theatre of the absurd, created by playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco after WWII, as a response to the many things that seemed too flawed for humanism to survive when existence and life purpose are threatened by forces too big and awful to ignore.

It all feels a bit like The Chairs, the absurdist play by Eugène Ionesco: a couple that feels detached from the world invents a parallel fake world through performance. In the metaphorical world they build, endless rows of empty chairs evoke a desperate human need for audience, recognition, society — the commons of attention and understanding. But these are phantoms. Their “individual” project to give a message to humanity collapses into absurdity.

Through the play, one gets the uneasy feeling that we have a need for a shared meaning, but can’t get it in a hyper-individualized void. It all feels like a bad dream.

Old Man: “We’re all alone, my dear, all alone in the world.”

(Moments later, they prepare chairs for imaginary guests — a community that never comes.)

It seems that the politically correct way to show discontent in our times is individual demonstrations, which people mostly do online. After all, the alternative would involve walking down the street on our own to show our grievances, which could be perceived as a lack of sanity. Sometimes, individualism can’t save us. The one-person demonstration isn’t new, but its performative absurdism is more prevalent now.

Individualism and the commons

Individualism has also brought many conquests from which most of us benefit greatly. To some extent, we can shape our own path, but some people have a vantage position to do so comfortably, as they have an environment that will counter any setback or career and life mistakes. But individuality and agency don’t happen in a vacuum; they depend on a culture, a collective.

How to balance the advantages of individualism with the commons is one of the questions of our times: Is today’s hyper-individualism detrimental and confrontational? On paper, the upside of individual self-realization is relatively straightforward—our autonomy to do things our way can reinforce creativity, economic freedom, and life purpose. Feeling much more than a “cog in the machine” is a necessary existential precondition for most of us.

Things get tricky, however, when we uncouple from a sense of community; in that case, individualism can feed victimhood and a sense of entitlement of “it’s either me or them.” With AI, our digital tools, already tilted towards flattering and engagement, are becoming more sycophantic to tell us that we have the right (or the need) to get the most for us and don’t need to care about anything else, as if we weren’t embedded in local communities, relationships, institutions, social structures, etc.

There was a time when our need for participation in the commons went beyond fanatically supporting the polarized political corner of our choice and asserting our supposed values by consuming (our house, our car, the brands of choice) and, to those who can, investing.

Misreading Ayn Rand

We’ve created an abstract individual who doesn’t feel responsible for the quality of the commons (public discourse, schools, infrastructures, public service, etc.), eliminating any need to reach agreements with people from different socio-economic environments who may think differently. Instead of expressing a need to engage with different points of view through public engagement, the tools we use subtly suggest (like the little demon whispering at the ear of cartoon characters) that isolated selfhood is the way to go. Many believe this is a recipe for disaster in the long run.

Tell me whom people look up to, and I’ll tell you the dominant trends of any particular era. Case in point: today’s most prominent self-made types celebrate selfishness and greed without afterthought, for their rationale is that there’s no better philanthropy than creating wealth. This could hold true in the past, when generated wealth left a trace through jobs, taxes, etc. Today, this isn’t the case, and there’s connivance with the established power to self-isolate capital wealth and gains from any taxation or trickle-down to society.

In practical terms, those lucky enough to generate wealth through capital gains grow richer and more numerous, while the rest — faced with stagnant wages and rising living costs — navigate a very different reality. Their frustration often spills into scapegoating, even as many continue to idealize selfishness and cosplay as Ayn Rand heroes, mistaking defiance for freedom.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with admiring ambition; I’ve read The Fountainhead and enjoyed it (I find Atlas Shrugged less convincing in depth and character). But at some point, even the wealthiest would benefit from contributing a slightly higher share to the societies that made their success possible. A stronger commons ultimately protects everyone better than any gated community or militant antisocial ethos ever could.

Plus, isn’t Ayn Rand’s literature all about fighting cronyism and entrenched, exclusivist oligarchies? I must have misread the whole thing.

Nothing to see here

Perhaps the least boring and most meaningful post-existential philosophy today comes from German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han; through his writing and Generation X looks, he connects to the zeitgeist in a very modern and at the same time indie, deplatformed way: he’s not a puppet of American traditional media, nor the ecosystem of heterodox podcasts, nor the go-to name to drop for media and pseudo-intellectual pundits that show up in your feeds. He’s not charging for engagement, and it shows (in a refreshing way).

Byung-Chul Han explains how contemporary society has progressively accomplished the gamification of reality, reframing many domains of life (health, education, personal identity, perception of success and happiness…) as matters exclusive of individual choice and responsibility.

The online environment and the self-help industry, from influencers to established brands, play into the apparently positivist side of this rationale: Having a hard time making ends meet? Sorry, it’s your fault. Either you’re doing something wrong, or you’re not working hard enough. In any case, it’s your fault. Struggling to adjust to familial and societal expectations? It doesn’t have anything to do with systems or institutions; it’s all your failure, you own it. And don’t waste your time complaining, just buy supplements and listen to toxic self-help to get back on track (and, if you can’t pay it all at this moment, take credit card debt or use Klarna).

In this context, we have internalized the need to continually optimize ourselves, as social media revolves around self-branding and the performative individuality seen in successful influencers. Individual self-representation is so amplified that brands, companies, and institutions (including politicians) have realized that associating with influencers is an effective way to convey authenticity and sell products.

In parallel, traditional civic participation has tanked. Phenomena like online engagement and home delivery for any conceivable product or service have increased much-needed convenience, but have taken it to such extremes that they’re taking a toll on neighborhood bonds. Most local associations are also in decline.

So, when people realize that, no matter how much digital entertainment and perks they get, they still feel a void, they become ripe to fall for any sort of engagement capable of substituting the lack of community. It’s a fertile ground for the emergence of cults and informal communities that promise a sense of belonging (like hyper-partisan environments and religious exclusivist circles, often organized through online platforms).

A 1986 speech at a business school

The symptoms of a more transactional, superficial, consumer-driven society have been clear for a long time. Before the rise of the internet, there was an already ongoing process of commodification of identity, polarization, and tribal individualism. And, in many ways, Wall Street’s “masters of the universe” (as Tom Wolfe calls bond traders in The Bonfire of the Vanities) can be seen as archetypes and precursors of the self-made techie.

The conviction that individual genius (or wit) should override norms was significantly extended in investment circles. The most profound change: the economic inevitability of market efficiency through deregulation morphed into technological inevitability, and the focus point moved from Manhattan to suburban San Francisco Bay Area.

On May 20, 2024, an obituary caught my eye: Ivan F. Boesky, Rogue Trader in 1980s Wall Street Scandal, Dies at 87. It was an interesting read, accompanied by no less interesting pictures.

On May 18, 1986, Ivan Boesky, at the time one of Wall Street’s most successful investors and regarded as a financial genius in a new era, delivered the commencement speech of Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. In that speech, he confided to his audience:

”Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.”

The audience greeted the occurrence with laughter and applause. After previous eras of ambivalence and moral tensions between self-interest and care for the commons, the ’80s embodied the “go-getter” spirit of successful individuals specializing in high-risk, high-reward trades.

Only a few months after the Haas speech, Boesky was caught in an insider trading scandal. As the rules of investing were being loosened, the Securities and Exchange Commission wanted to crack down on the excesses of bad actors. And so, the downfall of Dennis Levine, a merger specialist indicted for insider trading in early 1986, led to Boesky’s downfall for the same reason.

Gordon Gekko types

Boesky inspired the character Gordon Gekko in Oliver Stone’s 1987 film Wall Street, just by the time Boesky pleaded guilty, paying $100 million in fines. He was also barred from Wall Street, becoming a cautionary tale in an industry that was detaching itself from any correlation with the productive economy. Gekko was shaped after Ivan Boesky, corporate raider and activist investor Carl Icahn, and deal maker Michael Ovitz.

Of course, the 1980s financial hero never left; he simply changed hoodies. The message “greed is good” is now more powerful than ever, and today’s tech moguls are much more influential and wealthier than the wildest dreams of the most aggressive investors from the 80s. As for investing, the rules are being loosened, and a group of financiers is trying to persuade the public to invest heavily in private equity (or, better put, the private equity in which no powerful VC, big investor, or fund is interested) and crypto.

If the idea is to give “the little fellows” a chance to join the boom, as put by Andrew Ross Sorkin, somebody should also explain to small investors that the risks of losing big are also real, and should counter any irrational FOMO.

The mechanisms of engagement we’ve built are designed so we are convinced that the best way to overcome self-guilt for not succeeding like others are (at least apparently, according to social media) is to keep improving ourselves so we can meet expectations; but, surprise surprise, improvement is always a screen after things we have to buy before we reach the promised state. There’s little substance in that message, and it can lead to exhaustion and increased debt.

Personal expression vs. NPCs

Unlike say, the protagonist of Taxi Driver, Albert Camus and others were able to overcome a sense of dread and lack of meaning by walking out of nihilism and negativity through acts of personal renewal and connection with others. The first step is awareness itself—cultural, philosophical, aesthetic—. To walk from absurdity to real personal agency. Digital likes can evaporate, but real work on stuff that matters to us and others endures, just like a real, interesting conversation does.

Art (whether amateur or professional, funded or not) has been successfully used as an act of life affirmation, subversion, and hope throughout history. Subversive art is an antidote to guilt for not succeeding and nihilism insofar as it reminds us that imagination is universal, but the way we apply it to expression is truly personal and unique: it can’t be replaced by AI.

Heidegger’s concept of being-in-the-world is both a curse and a blessing: in today’s terms, we are all born to be player characters in reality, akin to the NPC metaphor for impoverished, controlled gaming environments like those described in The Matrix. We are already “in the world,” and this should be liberating, not the other way around. We’re embedded, and we exist beyond the stuff we consume and buy.

The tensions between extreme, directed individuality and our need to connect with others tell us that the commons is much more than a pain in the neck since it doesn’t depend entirely on us. Maybe the real act of rebellion now is not radical self-isolation, but acknowledging that interdependence can be compatible with individuality. We could imagine a future where individuality doesn’t erase community, but completes it.

In the end, the absurd stage is ours to share.

The chairs are empty only until we decide to sit down together, or at least do so sometimes, when it makes most sense.

Each one of us knows that we’re different, and that’s not only fine, but the most precious present of creation. Each of us is different. Each can cultivate their own agency, and to do so, there’s no need to buy stuff or to rely solely on the validation of others. Acknowledging at the same time that reality never happens in a void and the ultimate goal isn’t self-isolation.

The task, then, isn’t to abolish the self or to dissolve into the crowd, but to remember that the space between us is alive — and that’s where meaning grows. Maybe the commons begins again every time we pay attention, every time we share a gesture, a word, an idea that isn’t immediately performative and doesn’t seek utility.

A group where everyone took care of each other

Altruism starts with a mindset. Civilization has always depended on that fragile in-between — the unmeasured gift of presence. If we can keep that alive, the rest might just follow.

We shouldn’t be confounded by the success of Gordon Gekko types and those who support returning to our primitive roots. If they truly want to go back to restore whichever manhood they’re seeking, they should tell the whole truth based on evidence: when we needed to survive as isolated hunter-gatherers in a really mean and dangerous world, we showed up and cared for each other.

And no, we didn’t let the weaker members of tribal societies die because they weren’t as strong or were poorly adapted to extreme environments. Deep in their survival instinct, they knew they were stronger by sharing and understanding interdependence, not weaker.

Consider, for example, osteological studies in northeastern Patagonia (Argentina) who lived during the Late Holocene (~4000 to 250 BP). Many skeletons show healed traumatic injuries, and their remodeling patterns are clear evidence of long-term care.

In non-sedentary societies, that’s a costly kind of compassion: if a wounded person can’t hunt or travel, others must carry, feed, and protect them. Yet they did — and the bones prove it.

Picture the scene: a vast, wind-lashed steppe under a burning horizon; a wounded hunter unable to move on; companions adjusting their routes and diets, waiting, carrying, tending. In that desolate landscape, interdependence wasn’t ideology — it was survival.

People didn’t live in a vacuum, not even at the edge of the world. And neither do we.

(Note: if you read Spanish, drop me a line and I’ll get you access to a copy of a novel I wrote about the clash between Sapiens groups and Neanderthals in Europe, called La memoria de los lobos.) When there’s no civilization, what defines us?)