In a time of constant alerts, moral urgency, and outrage, attention dissolves into a permanent state of alarm, eroding judgment. Stepping back might be a good call.

The zeitgeist offers no respite. Only day traders and gamblers of futures seem to enjoy the ride. For everyone else, it feels as if we put something in the oven and forgot about it—until the fire alarm goes off, just before the smell of smoke spreads through the house.

Running to the kitchen, we blame our personal obligations (perhaps multitasking) for the kitchen’s rapid deterioration, knowing that it’s too late to avoid the mess. If what we forgot has enough grease on it, we might find upon opening the oven that a huge flame wants to escape, suddenly spurred by fresh oxygen.

In such cases, when the food is ruined and the smoke fills the room, we open the furnace again and use the fire extinguisher to put out the fire. In the best-case scenario, we’ll spend a great deal of time cleaning fire extinguisher dust and disposing of the carbonized food and utensils.

When are things worth our attention?

Reading the news in early 2026 feels a bit like forgetting about the greasy, very flammable food we put in the oven: we all feel we can’t affect big affairs but acknowledge we could have done much more when there was time for so. And now, we’ll settle with the least bad case scenario, personally and collectively.

We just started 2026, and many want to exit it altogether. Given the feeling I got from a few casual conversations, many are already seeking ways to escape a news agenda that shows excess, a lack of restraint, and loads of polarization.

One thing is already clear: doomscrolling isn’t the best way to stay meaningfully engaged. Many also acknowledge that it’s necessary to always keep up with the state of affairs, since their actions won’t amount to much, if anything.

Betting one’s tranquility and focus on affairs that depend on big ideological and political cycles can only be detrimental, if we are to trust the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who, in his Letters to Lucilius, advises him to keep his mind from becoming a hostage to events.

We have power over our mind and actions, and not over big outside events, which can be at once frustrating and liberating: if we can’t influence world affairs and our direct actions, at best, only transform our surroundings, why not see this as an opportunity to concentrate our attention on our work, family, relations, local engagement, etc.?

“There are more things, Lucilius, likely to frighten us than there are to crush us; we suffer more often in imagination than in reality. What I advise you to do is not to be unhappy before the crisis comes.”

On Future Fears (Letter 13), Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

The stoics and their ideal estate of “tranquility”

Is it necessary to remain aware and engaged, if only to cultivate civic responsibility? And, when does a self-perceived duty to stay informed and engaged with the zeitgeist become sheer masochism? We ask ourselves, how would someone like Seneca, who also lived in convoluted times (navigating, for one, the treacherous Julio-Claudian dynasty, serving corrupt emperors like Nero and experiencing exile), respond to these questions?

If we take his Letters to Lucilius as a reference, Seneca would remind us that the mind must govern itself and avoid being at the mercy of every disturbance, or it will become disturbed itself. There’s no virtue in suffering or in feeling outraged, nor is it a sign of civic responsibility to expose oneself to what inflames anger, fear, or despair (if anything, it’s a failure of judgment). He would add that people who care about others do not flee the world, but neither do they submit to its noise; instead, they choose carefully when to attend and when to withdraw.

How can we tell when a moment requires our attention? In this respect, Seneca would probably advise that, if our awareness improves our character, strengthens our sense of justice, or prepares us for action within our realistic power (which is very limited), then we know we ought to remain aware. By contrast, if it’s yet another public tantrum that we can’t influence, merely increasing our indignation without improving our agency, then remaining aware isn’t a citizen’s act but a way to lose our tranquility.

In his popular 2008 book A Guide to the Good Life, American philosophy professor and writer William B. Irvine explores the remarkable contemporary relevance of ancient philosophies of life, with special attention to Stoicism, particularly Seneca. Among the many topics he addresses, he turns to Stoic precepts to reduce worry, fear, and anxiety about worldly events and the future, offering what Seneca and others had to say to maintain their ideal state (tranquility) amid chaos outside.

Irvine talks about what he calls the Stoics’ trick of “negative visualization,” or thinking about worst-case scenarios to appreciate our current state: when we contemplate potential adverse possibilities, we recognize what is and what is NOT in our control; that way, we relinquish any attachment to outcomes that don’t depend on us.

If we aren’t hoping for a perfect world, a perfect present tense, and a perfect future, we’ll be ready to compromise and join others in working constructively towards better outcomes, a bit like Seneca’s precept to Lucilius in Letter 13. For those unfamiliar with Stoicism and its contemporary moral validity, Irvine’s book could serve as a spot-on starting point.

Compromise vs. escapism

At the start of 2026 (the year that should have focused on the many rights of the American Revolution in its 250 Anniversary, as well as its continuity and role as an example to the world), most of us are aware of the importance of such considerations, and not only for the sake of our peace of mind: acting civically can go wrong if our self-perceived civic duty is not seen as such by public forces that could harm us and allege their action was legitimate.

Henry David Thoreau would agree with Seneca’s premise, even though he would have probably radicalized it: instead of “inner sovereignty” (keeping our calm and our sense of focus and self-worth during convoluted times), Thoreau would have stressed the need to express moral refusal when the society in which we participate drifts into acts that we rationally analyze as immoral and contradicting our conscience. To the American transcendentalist, conscience overrides passivity and, if the State violates justice, then our duty is to resist if and when we get the chance to do so.

That said, to Thoreau, non-participation can also be a powerful form of action. Escapism, when done right, can serve as symbolic and deliberate noncompliance with actions lacking moral integrity. Suffice to say that Thoreau would be deeply suspicious of phenomena like digital engagement, outrage-baiting, and doomscrolling. Constant attention and opinionated outrage in the digital realm only amplify the sense of outrage and are not, by any means, acts of civil disobedience.

Unlike Seneca, Thoreau believed that the individual is the smallest unit of justice, and individual acts can be powerful precedents inspiring others: as in cases like the American Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. (who was inspired by Thoreau), reform often does not begin from the core of institutions but with people highlighting structural disfunction and injustice by peacefully refusing to cooperate.

Thoreau’s civic position is in many ways more analogous to that of another influential philosopher from Antiquity: Socrates. On the question of conditional civic duty—of engagement versus withdrawal to preserve one’s tranquility amid destabilizing noise—Socrates held that the citizen must remain publicly engaged, even at personal cost. For him, awareness was not the frivolous consumption of events, but an essential component of the philosopher’s relentless questioning of the city and its values. Seneca, by contrast, believed that awareness without real agency was a form of self-harm: exposure to public turmoil became ethically suspect once it corroded judgment rather than enabling action.

The power of the powerless

Socrates’ stance gains force from the way he lived—and died—it. He chose to stand his ground against unfounded and defamatory accusations that he could have avoided by accepting exile from Athens. Instead, he remained faithful to his principles and accepted death as the consequence. That death became a lasting symbol of civic duty and philosophical integrity, later examined and interpreted by two of his closest disciples, Plato and Xenophon, each transforming Socrates’ refusal to withdraw into a foundational lesson about the moral responsibilities of the citizen.

In a recent speech, Canada’s Prime Minister Marc Carney explained with an example what the risks are of choosing escapism over civic duty, even though Carney was extrapolating this reference to countries and public opinions, and not mere individual citizens:

In 1978, the Czech dissident Václav Havel, later president, wrote an essay called The Power of the Powerless, and in it, he asked a simple question: how did the communist system sustain itself?

And his answer began with a greengrocer.

Every morning, this shopkeeper places a sign in his window: ‘Workers of the world unite’. He doesn’t believe it, no one does, but he places a sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along. And because every shopkeeper on every street does the same, the system persists – not through violence alone, but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false.

Havel called this “living within a lie”.

The system’s power comes not from its truth, but from everyone’s willingness to perform as if it were true, and its fragility comes from the same source. When even one person stops performing, when the greengrocer removes his sign, the illusion begins to crack.

Havel’s example is closer to Thoreau’s civic disobedience (and to Socrates’ stance) than to Seneca’s.

The true nature of escapism

Escapism isn’t cowardice but a necessary self-regulating mechanism to favor the proactivity of the long term and not fall for the constant reactions of the present tense, which aim to elevate our cortisone levels to levels that aren’t advisable.

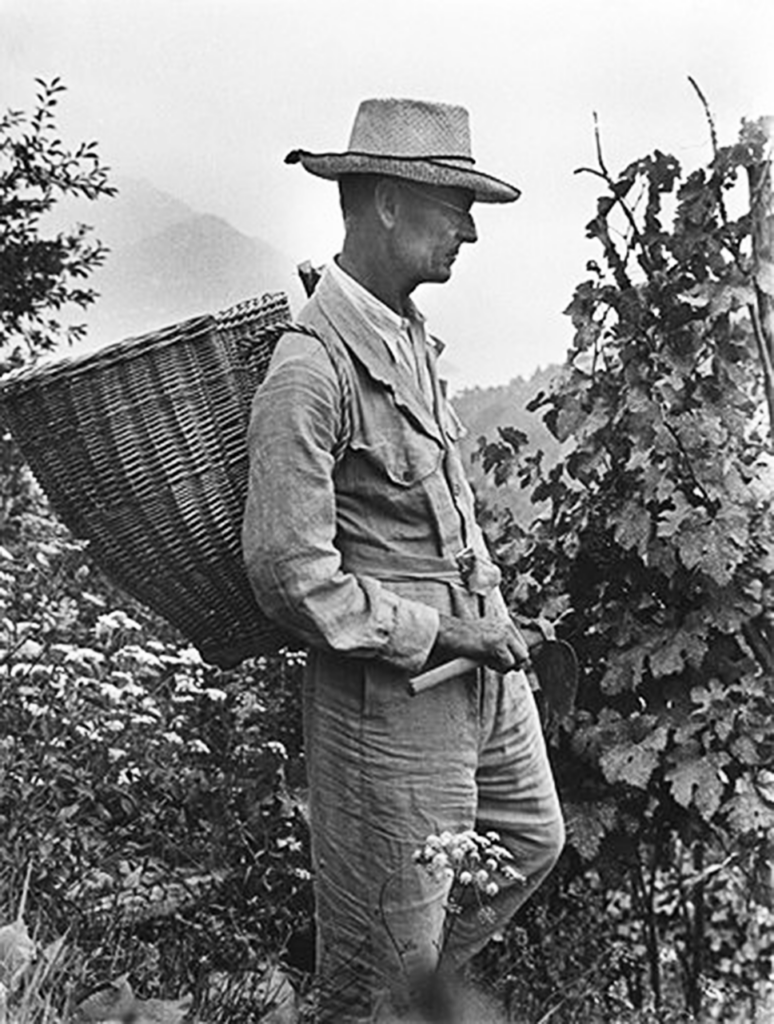

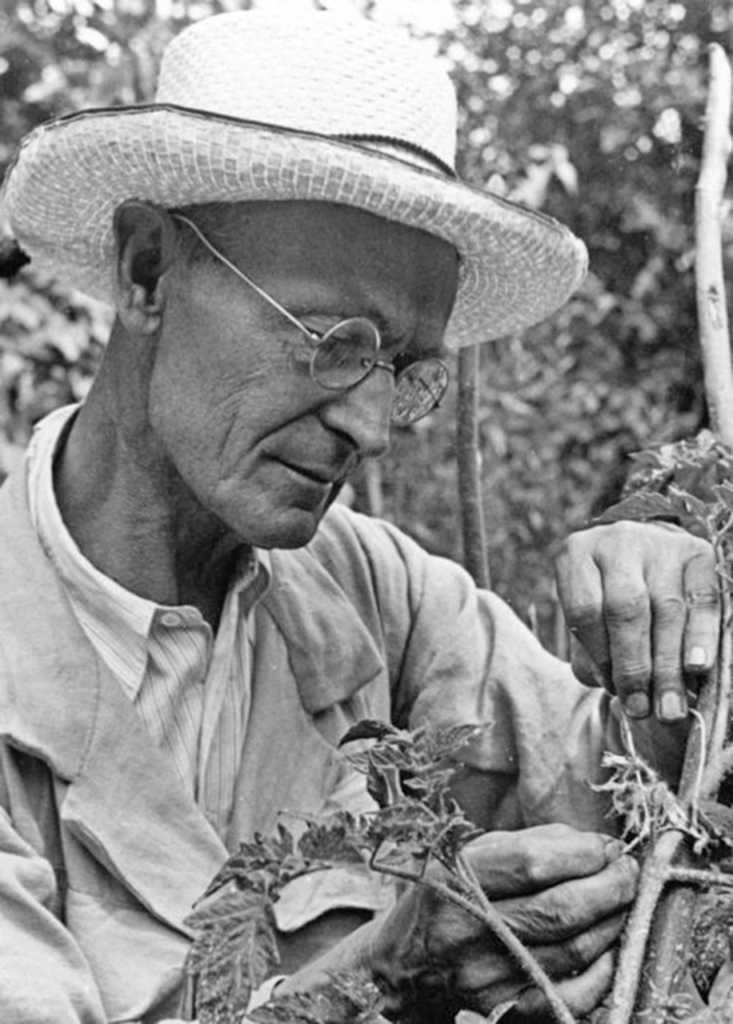

Yet escapism isn’t always constructive and nurturing, either. Those lucky enough to have found a purpose in their everyday activities may just double down and prepare their gardens for the early spring, or finish their shed, or work on their manuscript.

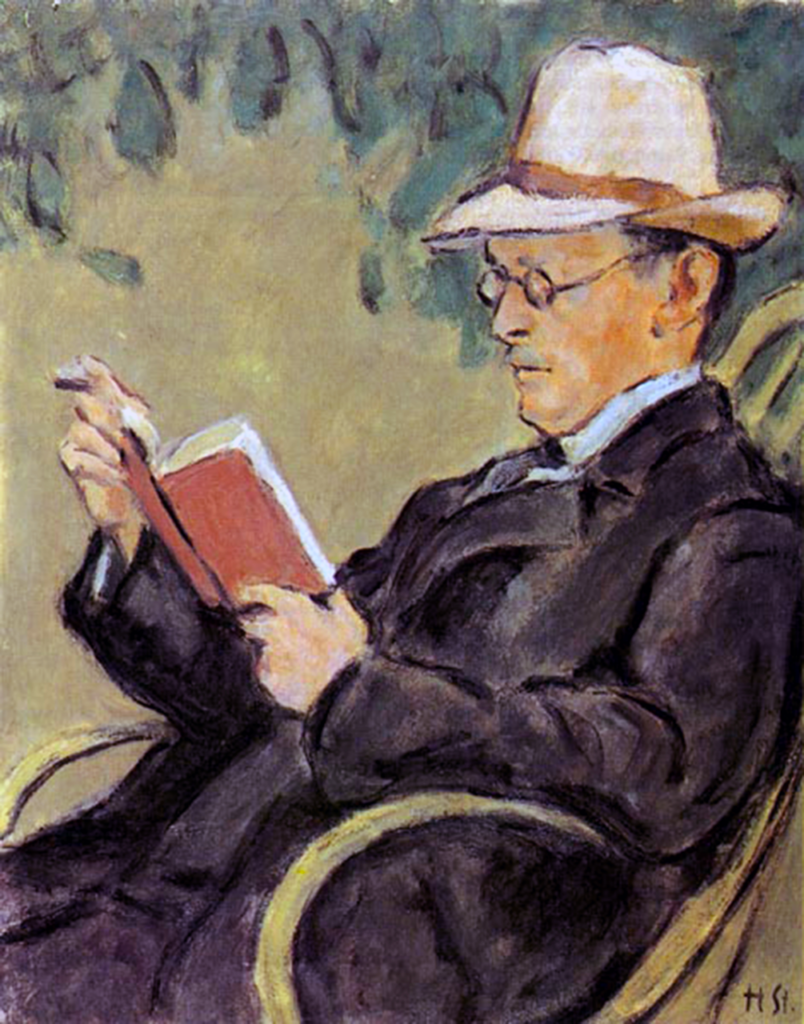

To the many who haven’t found a clear purpose or struggle to stay motivated, falling for the easy outrage brewing on our screens, there is, however, a constructive way to drop out and refuse to follow the outrage game: reading might be the best kind of escapism, promising the healthiest, most nurturing—and beneficial—type of withdrawal there is.

There seems to be a problem with this premise: long-form reading has been steadily decreasing across the board. Federal data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) signal a decline in book reading over the last two decades. However, shallow reading habits due to constant exposure to short-form digital content can grow less shallow; if there’s any New Year’s resolution that is attainable by anyone, doesn’t demand an upfront investment or recurrent payments, and always pays off, it’s developing a habit of reading books that matter.

Reading may feel passive, but studies show it’s the opposite: it demands that we stay cognitively active and focused, firing the most reflexive, non-reactive parts of our brain while nurturing our sense of worth and autonomy. When we work on something we like or find our path during a reading, we forget about time without feeling numbed and anesthetized.

Unlike digital apps and substances that release dopamine and reduce activity in the areas of our brain governing self-control and long-term planning, reading slows time without numbing or overstimulating our nervous system.

Reading long form (or, much better, books, preferably in paper format) prioritizes context and nuance, associated with actual knowledge, whereas the short, sugarcoated digital capsules on our screens attempt to stimulate outrage by design, with confrontational headlines, brevity, and moral shortcuts.

If doomscrolling isn’t actual civic duty, is reading?

Reading meaningful long-form content instead of doomscrolling is not a civic duty in the narrow, procedural sense. For one, it does not produce immediate outcomes. And yet, over the long term, it has been the most effective way to deeply influence how we act, vote, resist, and relate to others. Reading does not mobilize crowds, but it forms judgments. It does not generate instant consensus, but it cultivates discernment—the rarest civic virtue amid hyper-polarization.

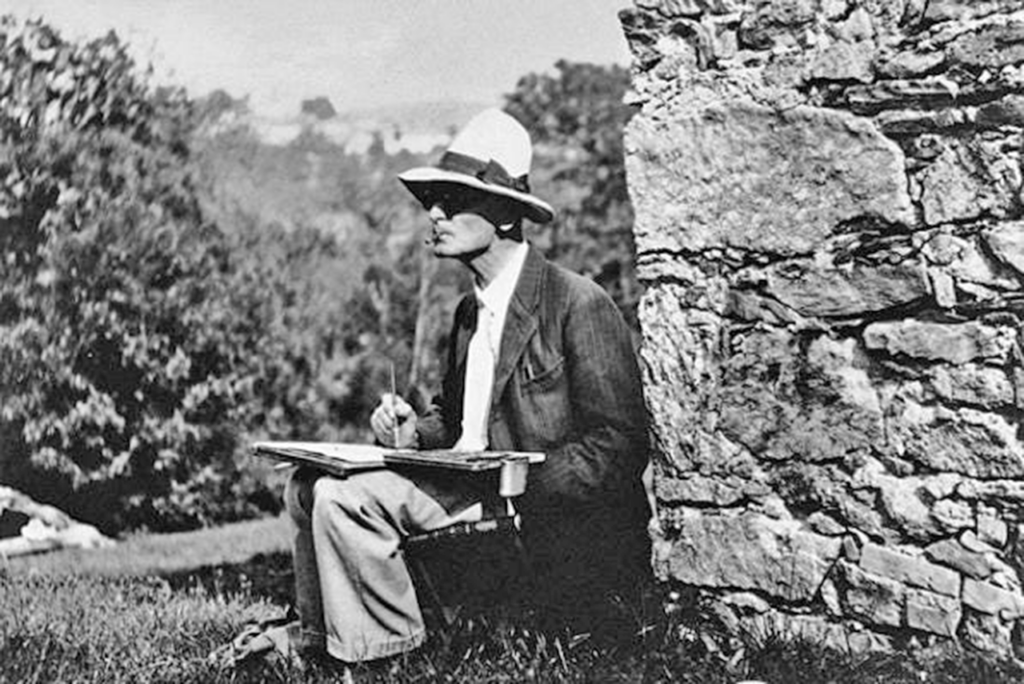

The French Renaissance philosopher and essayist Michel de Montaigne understood this well. Living amid the French Wars of Religion—a period marked by massacres, fanaticism, and ideological absolutism—Montaigne did not take to the streets, nor did he write incendiary pamphlets. Instead, he withdrew to his tower, surrounded by books, and began to read and write slowly.

His tower wasn’t the “ivory tower” of an out-of-touch rich snob. His Essays were not an escape from the crisis of his time, but a response to it: an attempt to preserve moderation, skepticism, and intellectual humility when public life had become a theater of certainties and bloodshed.

Montaigne was neither a coward nor an aloof intellectual sheltered from reality. He served as mayor of Bordeaux, navigated dangerous political terrain, and witnessed violence firsthand. His retreat into reading and writing was not disengagement, but a refusal to let fanaticism colonize his mind. He believed that shaping judgment mattered more than winning arguments, and that the most durable form of influence was indirect, delayed, and often invisible.

In that sense, Montaigne practiced a form of civic responsibility oriented toward the future rather than the present petty emergency. He wagered that cultivating clarity, tolerance, and self-knowledge in individuals would outlast the passions of the moment. His work did not stop the wars, but it survived them—and went on to shape generations of readers navigating their own periods of upheaval.

If we were to trust Montaigne’s judgment, reading and writing without a tone of urgency is not an abdication of civic life. Rather, it’s a long-term investment in the kind of inner architecture without which civic life collapses into noise, imitation, and ritualized outrage: what we absorb, reflect on, and pass along—often quietly, through example rather than declaration—becomes part of the moral atmosphere others inhabit.

Deep readers vs. headless chickens

In times that reward speed, reaction, and alignment, choosing to read deeply may be one of the few ways to remain intellectually sovereign. It is not a refusal to care, but a refusal to be rushed into borrowed convictions. And while its effects may be slow, they are cumulative (transmitted through language, habits, and values in ways that no headline or feed ever could).

Considering escapism does not mean defending indifference or ignorance of what’s happening around us. It is to argue that attention is a finite moral resource, and that squandering it on permanent emergency can quietly destroy the very capacities—judgment, courage, imagination—on which meaningful civic life depends. Escapism, when practiced deliberately, is not chickening out. It is often an act of discipline.

The brain’s danger system is not built for constant alarms, and permanent outrage hijacks our very abilities to discern the signal from the noise. Like Aesop’s fable The Boy Who Cried Wolf, when threat signals are repeated without much visible consequence, the brain adapts, setting a new perceived “normal.” Threat habituation can leave a whole society passive when the real danger comes.

Tragically, the tools we’ve built train the brain to look for drama, villains, spectacle, missing the slow threats: the actual transformation of the baseline reality around us. And, if a society that is constantly panicked is less capable of responding to real crises, then escapism is a survival mechanism—an effective one.

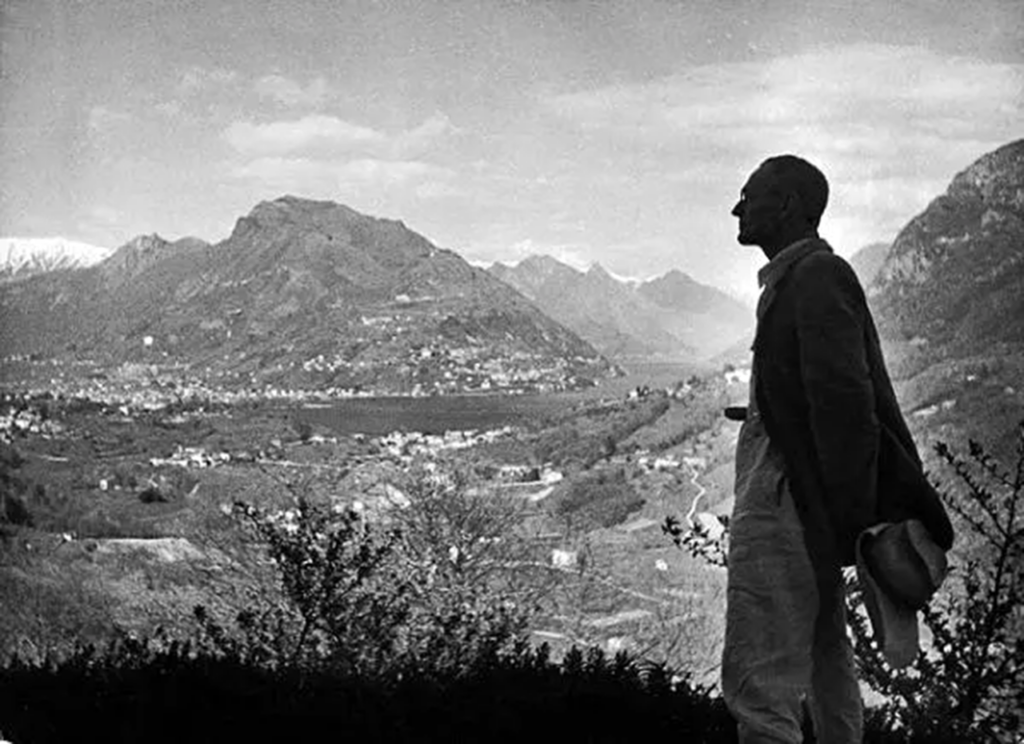

Escapism, when practiced deliberately, is an act of discipline. History offers ample precedent. During Europe’s interwar period—a time marked by mass propaganda, economic collapse, and rising totalitarianism—many of the intellectuals we now admire chose forms of withdrawal not because they were naïve about politics, but because they understood how corrosive constant immersion could be.

Escapism done right

At the core of the crisis in the then-convoluted Mitteleuropa, German writer Hermann Hesse retreated into spiritual and psychological exploration, producing works that offered inner orientation as outer frameworks collapsed. Choosing escapism by reading Steppenwolf and Siddhartha is a pleasure; I did so when all I could hear around me was associated with nationalism, while living in Barcelona until 2015.

Stefan Zweig, author of a seminal book on this, The World of Yesterday, sought refuge in a cosmopolitan humanism precisely as nationalism made public life intolerable. Another reference in the region, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, withdrew almost entirely from political discourse, cultivating a poetic interiority that refused to be conscripted by ideology.

None of these figures was ignorant of their times; they were, instead, acutely aware of how easily attention could be weaponized. Their retreat was not passive. It was a wager on the long term, preserving forms of thought, language, and inner freedom that might outlast the present frenzy. Escapism functioned less as flight than as moral triage, a decision to protect what could still be saved when public discourse had become saturated with hysteria and false urgency.

Seen this way, escapism aligns more closely with Seneca’s insistence on self-governance than with caricatures of apathy. The Stoic did not urge abandoning the world but rather avoiding becoming a hostage to it. To focus on one’s work, family, friendships, and local responsibilities is not to ignore the world’s fires; it is to refuse to let every distant blaze burn down one’s own house.

If there was a 20th-century thinker that bridged the differences between Seneca’s (and Montaigne’s) escapism and Socrates’ and Thoreau’s symbolic civic compromise to inspire others, is French writer Albert Camus, for he equally mistrusted withdrawal and noise, especially if they became easy formulas (or mere excuses for people to remain naïve and disengaged while virtue-signaling at the same time).

Between escapism and compromise

Camus’ position is uncomfortable: unlike many other intellectuals of his time, he didn’t try to confront fascism and occupation by praising Stalinism. His early nihilism (which he called “absurdism”), as explained in The Myth of Sisyphus, holds that lucidity is often painful because we see how futile our position and views are in the great scheme of things.

But later, Camus wrote The Rebel, in which he warned against a type of engagement in which the end justifies the means (for example, killing others in the name of ideals) because it erased moral limits and whitewashed terrorism and atrocities in the name of freedom.

What Camus defended instead was lucidity: a form of engagement grounded in restraint, attention, and fidelity to concrete human relationships. In The Plague, his characters resist not through grand gestures or constant agitation, but through steady, often monotonous acts of care—doing their jobs, tending to others, refusing despair without indulging in heroics.

In this sense, Camus stands as a bridge between Seneca’s self-governance and Thoreau’s moral refusal. He reminds us that resistance loses its meaning when it becomes automatic, and that withdrawal only loses its meaning when we do it for comfort rather than clarity.

What’s left, however, is harder to accomplish and doesn’t bring false comfort: the courage to remain lucid, to accept limits, and to act locally without surrendering one’s conscience to the fever of the moment.

Oxygen and flames

To follow the image early in the kitchen (a scene which actually happened, though luckily didn’t escalate), when the smoke alarm goes off and the oven bursts into flames, flinging the door open in a panic often makes things worse. The sudden rush of oxygen feeds the fire; the damage spreads. What helps is less dramatic: turning off the heat, closing the door, stepping back long enough to act deliberately. The goal is not to deny the fire, but to prevent it from consuming the entire house.

Much of our present engagement with the news resembles that panicked rush. We fling open the oven door again and again, flooding the situation with attention, outrage, and commentary—only to discover that we are inhaling more smoke and gaining little control.

Escapism, when practiced deliberately, is not walking away from the kitchen forever. It is knowing when to close the door, when to let the flames starve, and when to return with a clear head and a working extinguisher.

And if we are to avoid burning down the house next time, we may need fewer people standing around the oven shouting—and more who quietly remember how to cook, how to clean, and how to keep a home habitable when the alarms inevitably go off again.