Does the global housing market slump represent opportunities for first-time buyers?

It might seem counterintuitive, but a pervasive housing market slump makes buying more difficult for the majority (those relying on loans and salaries, unable to tap into savings). Inflation makes borrowing more difficult and expensive while transforming employment and eroding purchasing power.

Suddenly, instead of looking confidently for better job offers, workers feel they can lose their job and fall behind on their payments. Big strategic decisions (considering relocation to more dynamic areas, opening a business, getting a new car, buying a house) don’t seem that easy anymore.

Instead of cheering the sudden global downturn in the housing market, aspiring buyers should be concerned and prepared to act with caution: homes are the largest component of personal wealth but also the biggest debt risk. Rising inflation means less purchasing power over time, especially felt by those dedicating a more significant part of their income and savings to everyday needs such as gas, food, and mortgage or rent payments.

It also makes it more expensive to buy new homes, pushing down home values. Here’s a bit of macro context by The Economist:

“Lower house prices also hurt growth in a second way: they make already-gloomy consumers even more miserable. Worldwide, homes are worth about $250trn (for comparison, stock markets are worth only $90trn) and account for half of all wealth. As that edifice of capital crumbles, consumers are likely to cut back on spending. Though a cooler economy is what central banks intend to bring about by raising interest rates, collapsing confidence can take on a momentum of its own.”

The sentiment you don’t want to feel

The current inflation spiral is interconnected and as global as the pandemic that created the conditions and nourished it. It reduces not only wealth and consumption, as Kenneth S. Rogoff explains in Foreign Affairs, but also our perception and expectations over the medium term:

“More generally, higher interest rates discourage borrowing and encourage savings, damping consumer demand. Higher interest rates also cause firms to reevaluate long-term investment projects, directly and indirectly lowering their demand for workers.”

The anxiety appears in projections made by analysts, such as the last projection by Oxford Economics on housing across 20 developed countries, but it’s also felt on the street. When home prices have experienced correction across the board, consumer spending and construction have stalled, whereas credit has become more expensive. This time around, growth in the world’s economy could shrink from 1.5% to 0.3% in the lowest scenario predicted by Oxford Economics.

One more caveat. There’s a difference between the housing slump we are entering and the subprime market crash in 2008: then, low interest, excessive borrowing, and lack of proper risk assessments on loan concessions and derivatives were only apparent after a decline in house prices in the US in 2006 and 2007, but the housing bubble burst in the US and smaller markets (such as Spain) spared China.

This time, the biggest risk is in the emerging economy: China’s property market has accelerated its fall, and the orderly deflation of a housing bubble acknowledged by the Administration could not happen according to plan.

The big “if”: China’s housing market

In August 2020, China approved a “three red lines” policy while warning in a campaign that “houses are for living, not for speculation.” But the policies aimed at reducing the country’s exposure to the potential collapse of real estate behemoths such as Evergrande, a company in technical bankruptcy incapable of restructuring its massive debt without declaring very powerful big losers.

There are more concerns. The recent controversial party congress, in which Xi Jinping publicly purged dissenters within the party’s high ranks, shows how the country could deal with economic disasters such as a real estate bust. The recovery from previous quarters of COVID pervasive lockdowns could be more fragile than forecasted if companies aren’t capable of finding liquidity.

China’s government encouraged bank credit to several of the most exposed property firms, and several provinces coordinated to streamline approvals of home sales and property loans to bring liquidity to the sector, but the inability of most companies to access bank liquidity in 2022 has fueled, according to analysts, loans coming from shadow lenders, from trust companies to “small loan firms.”

China’s real estate sector represents more than one-quarter of the country’s economy, and 10 of the most indebted property developers in the world are from China. Shehzad Qazi, managing director of China Beige Book International, warned one year ago about the situation:

“There is the realization that the former growth model – which involved high levels of debt, high levels of investment, and high levels of growth – doesn’t work anymore. Beijing realizes that it needs to shift to a more sustainable model, which means a slower pace of growth.”

Dreams of a “not wealthy enough” wealthy young couple

If we switch from the macro perspective to the view of potential real estate buyers, things don’t add up either: in most economically dynamic areas of, say, the United States, prices will most likely level out rather than falling to pre-pandemic levels due to cumulative high demand and scarcity of available inventory in relation to population and salaries.

Yesterday, I met a couple of young professionals with no kids living in a 2-bedroom rental house in Palo Alto (it rarely gets more expensive than around them as far as sale or rent prices go in the US).

With no traffic to their nearby jobs, steady salaries, and no debt, they consider themselves very fortunate and see their rent as “highly advantageous” despite paying slightly under $4,000 a month.

Unlike some of their neighbors, who work remotely some days a week post-pandemic, they are physicians from a nearby hospital, and managing to live in its proximity was very important since presence at work and a good work-life balance felt like a safety net during the worst moments of the pandemic. But their two salaries make it very difficult to own a house, or even a condo, in an area like the one they can currently afford if they rent.

Our conversation didn’t go further, which ended with the young physician expressing hopes that a potential price correction in real estate increases the odds of them “buying” in an area used to sales paid in cash and over the asking price. But inflation and interest rates are trending upward, which makes buying a first home more challenging. Even if prices drop to 2020 levels, the lack of new housing in the area makes any real downturn very unlikely.

Borrowers are interconnected and dependable, like it or not

Things haven’t been rosier in much of California, and aspiring homeowners are holding their breath: could a cooldown in the housing market benefit their aspirations? The Economist points out that as prices may stall or even go down, buying gets more —not less— challenging. For one, the same economic conditions that cause house prices to fall “simultaneously imperil the chances of would-be homeowners.”

“Unemployment rises and wages decline. If interest rates jump, people are able to borrow less, and mortgage lenders tend to become more skittish about lending.”

As it becomes more difficult to afford a deposit and qualify for a mortgage, prices could eventually meet a weakened demand in the markets that don’t face hyper-competition of high-income, locally employed aspiring owners; real estate investment funds; and international investors in search for safe wealth diversification.

The United States and Canada experienced a surge of rural home and second-tier cities (such as Boise, Idaho) sales during the pandemic, driving a two-digit surge in prices in areas that are now particularly vulnerable to cooling demand. Homeowners who left the city for the countryside, which inspired press articles that announced a big lifestyle shift, were a part of the price hikes since 2020. Now, those experiencing doubts about their choice will face significant contingencies to sell their homes at a price exceeding their investment, were they to decide or are prompted to change career paths and forced to relocate.

It’s also getting more difficult for potential buyers to qualify for more onerous loans. Consequently, transactions are already declining in several countries: they fell by a fifth in August in the US compared to 2021, according to the National Association of Realtors; something similar is happening in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several European housing markets.

Learning from past bubbles

Interest-rate rises have transformed mortgage rates to levels the youngest population can only read in history books. Whoever took for granted 30-year fixed-rate mortgages at rates below 3, as they were recently in the American market, will now face a 7% rate (it’s also over 7% in New Zealand and over 6% in Britain).

Unlike in other real estate markets, fixed-term borrowing is pervasive in the US mortgage market to avoid the impact of potential interest rate hikes among the most exposed buyers, with loan payment rises being less aggressive than in markets that have favored floating rates, a legacy from previous mistakes: The 1973 oil crisis triggered inflation and, by the late ’70s and early ’80s, 30-year mortgage rates reached 18%.

Fixed-term borrowing and relative energy autonomy, if compared with most OCDE countries, won’t help Canada if the housing downturn confirms the country’s real estate market has experienced a housing bubble: the housing investment as a share of GDP and the amount of highly indebted households could affect how life is perceived —and how much consumption spending gets affected.

As inflation drives up interest rates and most home loans get more expensive, it gets more difficult to buy new homes even if their price stalls or drops. However, rents are maintaining their rising trend in many places despite worrying inflation trends and concerning prospects of energy prices this winter.

House prices are already falling in nine rich economies, though the main concerns aren’t coming this time from the same economies.

Household debt and playing long term

Households in some of the countries most exposed to the effects of the global financial crisis in their local housing markets —the United States, Japan, Italy, Britain, or Spain— have reduced their household debt as a percentage of their disposable income and are not as exposed as they were in 2008. But, this time, several other countries that lacked a housing bubble and an excess of borrowing have followed the opposite trend, as families have amassed concerning amounts of debt in the last years.

Even small rises in interest rates in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, or three Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), will affect borrowers paying floating-rate mortgages. They are already facing a radical reduction in their disposable income as food, gas, and heating prices have climbed rapidly in the last months.

This time around, the global housing slump could be led by Canada, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Taiwan, and Finland. Home prices could fall 14% from their peak in Australia and Canada, slightly more than in the US and Britain:

“Economists at the Royal Bank of Canada expect the country’s volume of sales to plummet by more than 40% in 2022-23—exceeding the 38% drop in 2008-09.”

Hobos and runaway trains

“Globalization feels like a runaway train, out of control.”

This commentary doesn’t come from a fringe media commentator or populist politician trying to bank on the current discontent, but a thought-after pondering of a rather unexciting politician of a different time: Gordon Brown, made of the same material of those long-gone civil servants putting country over party when things get rough.

It feels like a whole different era now that we feel fully immersed in pervasive discontent, but some Britons ask themselves what went wrong to get the likes of Gordon Brown ostracized from public life, while spectacle politicians (or “chaos engineers,” as Italian political scientist Giuliano da Empoli calls them) have taken over.

Because Brown, first a credible Chancellor of the Exchequer for 10 years with Tony Blair and then, from 2007 to 2010, Britain’s Prime Minister, had warned against a world economy that had not learned the hard lessons of the subprime crisis, later turned Eurozone debt crisis. His views of the current challenges faced by Britain, Europe, and the rest of the world, are more prescient than ever.

Born in 1951 (hence much younger than the likes of Joe Biden and Donald Trump), Brown belongs indeed to a former world of politics, one in which there was a sense of duty with the reality that mandated leaders to face inconvenient truths and, if necessary, take difficult decisions for the common good —even if they meant risking one’s own luck in short term political cycles.

Unpopular necessary experts

Lawrence Summers, another economist in public duty during Brown’s years at the Exchequer as turn-of-the-century US secretary of the treasury, has faced a similar public fate for similar reasons, not wanting to pander to the most popular economic opinions of every moment (unlike, say, hyper-partisan hooligans from both left and right, some of them Nobel prize winners, some others pure hubris).

Both Brown and Summers warned about the missed opportunity of fighting perversions of globalization by redefining transnational relations and capping financial speculation (unrelated to the productive economy, capable of destabilizing by shorting entire sectors and economies). They have also been among the most credible experts depicting the risks faced by a world economy overheated by post-pandemic stimulus packages that had nowhere to be spent due to production and supply chain setbacks.

In early August, Brown called for an emergency budget to prepare for winter. It was a warm August, and the Conservatives were campaigning to elect their new leader. Yet, Brown was looking at inflation and energy prices affected by the war in Ukraine and the last OPEC decisions, aware that models were bringing the median price of UK winter energy bills to new records, with more than half of UK households spending 10% of net income on fuel costs.

By January, over 4.2 million households (11.6 million people) will spend more than a quarter of their net income on fuel. Yet Gordon Brown was warming about the situation in summer when the short-term political show was onto other things. Lizz Truss finally got elected, and her lack of touch with the reality faced by British families was clear not long after.

Perverse incentives and primary elections

Britain has indeed experienced in the last few weeks what “sentiment” in markets can do to a country’s short-term economic prospects and prestige. The implosion of the UK’s government has been entirely attributed to Liz Truss’s recent mismanagement, by announcing the biggest tax cut in half a century in a moment of rising worldwide inflation, rising energy crisis before winter, and technical recession.

The shortest-lived British Administration deserves an essential part of the blame. Still, the trouble goes back years and affects not only the Tories but the entire political spectrum, transformed once the parties’ bases adopted US-style primary elections to elect “popular” leaders for the bases, yet not necessarily ready to adopt pragmatic, realistic policies in delicate turning points.

If adopting party primaries in most consolidated democracies seemed a necessary and welcoming improvement and democratization of leadership, its outcome is less rosy than expected: in times of turmoil, ideological candidates that resonated with highly mobilized factions of parties, yet making extremism more likely, which increases potential polarization and dysfunction in governments while often paralyzing as well their opposition (Jeremy Corbin tried to fight one type of fringe populism with another blend of it, which also turned out to be pro-Brexit).

But, as primaries have moved power from parties’ bureaucracies to the rank-and-file, an apparently anti-elite procedure, the barriers that tried to secure moderate candidates fell too, which would explain the rise and fall of Liz Truss, as well as the damage she managed to do in such a short mandate. Data clearly shows that those who can vote in parties’ primaries are not representative of society as a whole.

As political scientists have recently pointed out, dues-paying members of parties (those who usually decide who becomes a candidate) bear little resemblance with the overall population they represent if they are elected as prime ministers. In the UK’s Conservative party, for example, due-paying members are overwhelmingly male: two in three; two in five are over 65 years old, double than in their society as a whole; and three in four voted for Brexit in 2016 (only 52 percent of Britons did, and only 58 percent of all conservative supporters).

Long winter ahead

When intellectually honest, pragmatic, and prepared politicians give way to those who will promise anything as long as it gets them to power, it’s extremism that takes over and not credible alternatives to old rank-and-file cronyism and dysfunction —writes Max Fischer in the New York Times.

Media (and social media) analysis isn’t helping either: the fragmented environment is experiencing its own process of radicalization and hyper-partisanship as information driving most clicks stresses dubious claims to attract attention.

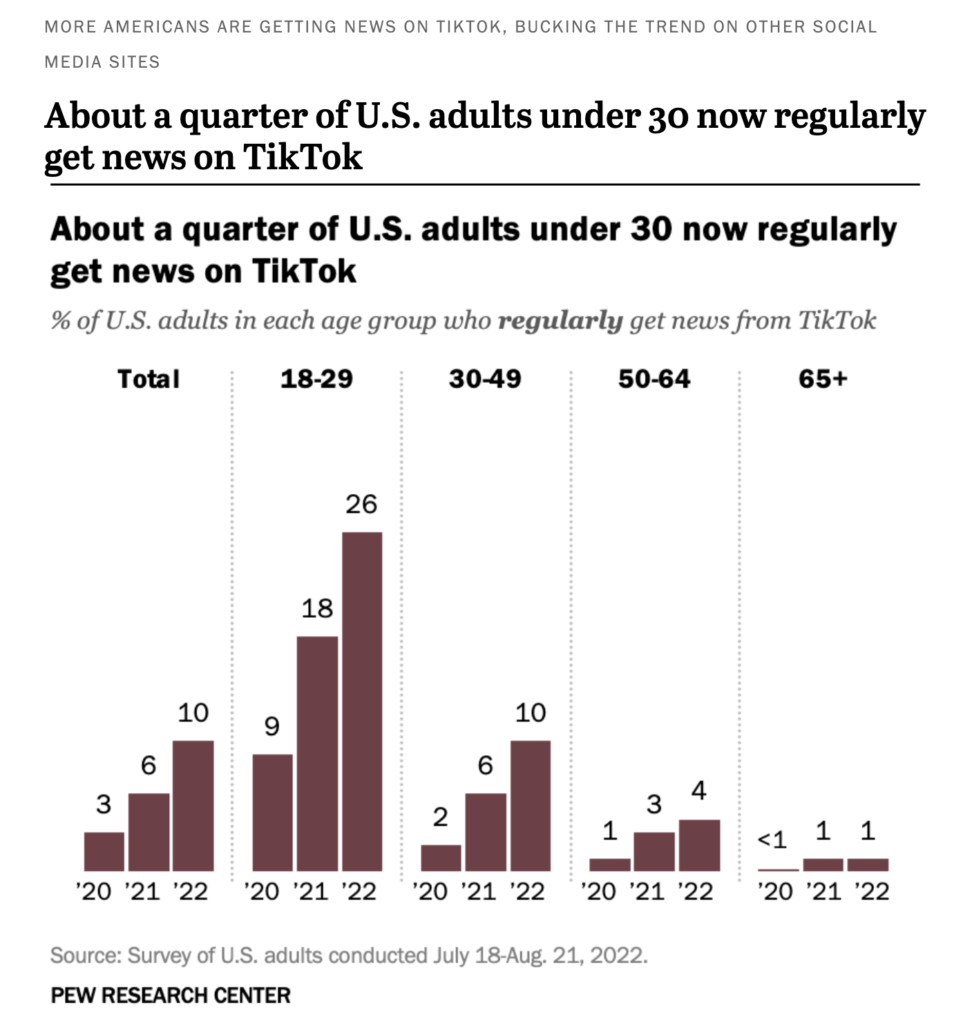

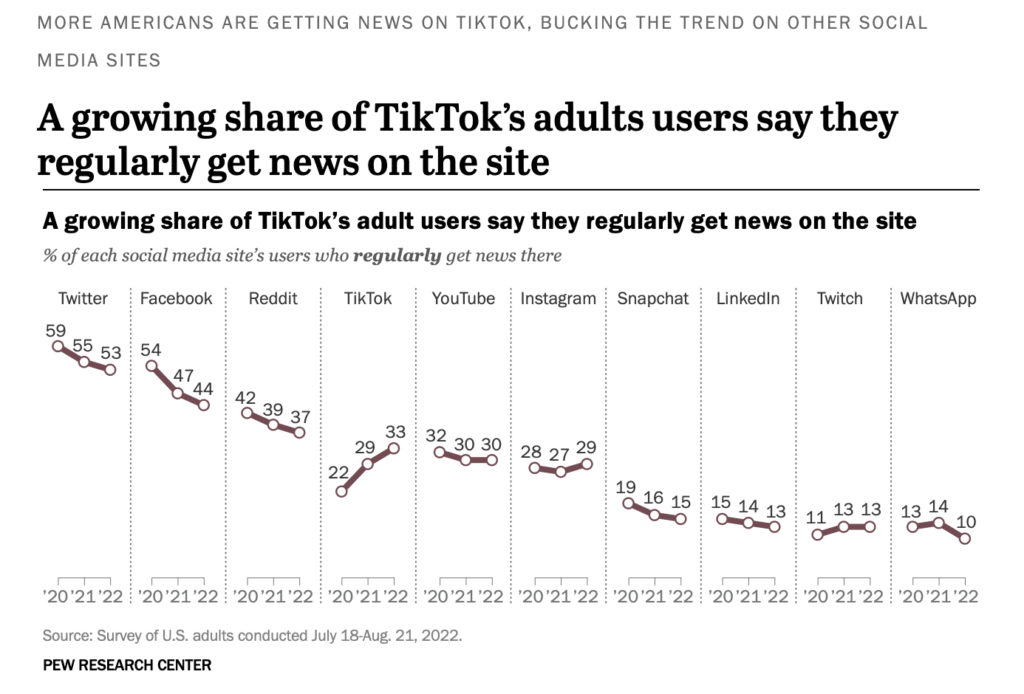

As the United States approaches midterm elections, social media networks deal with disinformation and its potential backlash from those who consider moderation (for example, banning personalities from spreading conspiracies and misinformation) as a free speech issue. Because of the public battle over the perception of moderation, TikTok —controlled by the Chinese company ByteDance— is the only social network rapidly growing as a news source, according to Pew Research.

Popular ideas and good ideas

Smaller players try to foster growth by attracting fringe content. Although Parler, Gab, Truth Social, Gettr, and Rumble represent a tiny fraction of the total digital media sharing environment, they are a factor in today’s polarization. Or, according to one researcher from the Institute for Strategic Dialogue:

“Nothing on the internet exists in a silo. Whatever happens in alt platforms like Gab or Telegram or Truth makes its way back to Facebook, Twitter and others.”

This reality is consistent with those who believe that banning a few personalities from social media doesn’t solve any issue while creating new ones —for example, by entertaining the idea of partisan censorship among conspiracists.

Fragmented media consumption, polarized public opinion, elected party leaders ditching “boring” candidates of consensus-based politics in favor of unorthodox leaders flirting with fringe ideas (coming from the most vociferous factions of their own parties). The phenomenon isn’t isolated, nor are the consequences of pandering to the public with popular policies for electoral reasons.

As a candidate, Joe Biden promised a giant stimulus to boost the post-COVID economic recovery, even when the recovery was already underway, and Donald Trump had already passed a $900 billion COVID-19 relief package in December 2020. The economy was rebounding strongly, and heavyweight experts (like, once more, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, among others) had already warned —Summers did it in early 2021— that the economy was dangerously overheating and, this time, it could be disastrous: unlike in previous situations, this time there were severe supply constraints for consumers to allocate their reinforced purchase power, and more people with money to buy things would rapidly rise prices due to supply chain dysfunctions.

Looking for the good trouble

Larry Summers and, internationally, Gordon Brown, among others, remained less popular than those prominent commentators cheering the Biden administration to pass a $1.9 trillion stimulus package, like Nobel laureate Paul Krugman.

Summers wasn’t playing Nostradamus. As Kenneth S. Rogoff explains in a piece on inflation for Foreign Policy, a demand shortage and severe supply constraints could not play well with the idea of throwing another huge stimulus into the economy, and this time Americans wouldn’t be able to buy abroad. Demand exceeding production in several key sectors and the consumer market would lead to inflation even though it had not occurred in decades. Unlike several of his colleagues, Summers warns about potential byproducts of bad (but highly popular at the moment) decisions before they happen and not after the fact.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Gordon Brown wasn’t being lucky himself with the British public opinion, with media and social networks more aware of the histrionic fuss from some of the least consistent tory politicians.

Experts who have served in positions of power are among the most unpopular figures influencing (or unnerving) public opinion. The credibility of the likes of Larry Summers and Gordon Brown comes from their scrupulous attitude with evidence and experience: instead of selling fairy tales, they explain why there’s no easy way out in situations such as global inflation and some of its consequences, from a loss in purchasing power to a housing market slump.

Inflation and recession: communicating vessels

Free societies need such public figures, even if few like realistic, pragmatic types in times of patriotic gesturing (which, one can argue, is also a consequence of difficult times). Such realists warn us about the dangerous odds of getting into a recession if political decisions are particularly clumsy, no matter where they come from.

They may, for example, point out that if the US government approves two consecutive aid packages amid production and supply chain chaos, it could be the trigger to get into an inflationary era that only a recession can cure. Or, when a government announces the biggest tax cuts in a generation instead of preparing the public opinion for a long inflationary winter, they may already advise us of how to get out of the troubles we are heading to.

Larry Summers warned about high inflation when it was painfully unpopular to do so (the public knows that interest rate increases affect, for example, stock portfolios, which should make us wonder why members of Congress continue trading stocks while working on decisions that might affect the stock market). In June 2022, Summers and others were among those already warning why today’s inflationary zeitgeist is closer to the Great Inflation from the seventies and early eighties than we think.

Responsible experts and charlatans

If more than a year before central banks began raising interest rates (the US did finally act in March 2022), some credible expert is explaining what can go wrong if there’s a delay to act in an overheated, constrained economy, he is doing a public duty, especially valuable in moments of partisan belligerence and systems of power prone to sycophantic groupthink.

What’s popular among the electorate in a particular moment, or to the members of a party with voting rights (or to lobbies), is not necessarily what makes sense. And somebody must do the work of telling us compellingly in a way that we can understand. That said, how do we tell responsible experts from charlatans? Charlatans avoid being unpopular (or not being the center of attention: all news is good news) by all means and will either: pander to power; or appeal to people’s anger against it.

Unfortunately, China doesn’t tolerate such influential analysts if they become too uncomfortable with the regime (the fate of Li Weinliang, the Chinese doctor who warned about Covid-19 and died of it harassed by the local Administration, doesn’t invite optimism). We can guess what’s happening through the macro view of China’s troubles is being partially engineered by what the country’s Administration is willing to share and what it is willing to conceal.