In an age of bland scripts—human and machine—we’re oddly hungry for the stumble. The pause, the self-correction, the sentence that changes direction mid-flight.

Overhearing a family conversation at an airport, I realized we live in a moment when we still think there’s value in flawless skill, yet we enjoy pop culture, art, TV, and podcasts where interesting people talk from the top of their heads. We love to “see how people think,” yet our world still demands ritual formality.

As we enter a new era when machines create structured knowledge, we’ll come to value more the part that large language models struggle to replicate: the way we search, connect, and discover in real time, the way we sometimes evolve our thinking as we engage in a conversation. If done right, this process rarely feels like a preloaded sequence of words (though there are certainly people who feel like AI: highly articulate, even encyclopedic at times, but unable to transcend or invent).

Addressing a live audience isn’t a conversation if we don’t want it to be, but most of us cherish memories of the few professors and mentor figures who truly engaged in open dialogue.

A few days ago we got an invitation to give an “arts and culture” speech regarding our recently published book after Lou Fancher interviewed us for the Bay Area News Group, appearing on its subsidiary publications (the East Bay Times, the San Jose Mercury News, and many smaller publications from the region), and the question about “what to say” and “how to prepare arose.”

Knowing what you have to say vs. learning verbatim

Talking to one of my daughters about this, she feels very protective and wants to spare me from any embarrassment, so she recommended that I “prepare” and, especially, “learn things by heart.” In her world, perhaps the authority that comes from memorialization is the gold standard because it still gets studious friends to the top of their class. I told her my truth: I’ve always struggled to learn by rote, and I’ve always liked to understand the meaning of things. This can sometimes be detrimental, but it can also significantly help in life.

She wasn’t convinced. I tried to argue that “preparing” doesn’t mean being able to parrot a compendium of stories, but rather conveying the actual emotion and meaning of the work you’re trying to do. She still wasn’t convinced. My inability to explain to her why I like and seem to learn much more from “lectures” by people that don’t “lecture” but explain anecdotes and improvise about who they are, than from editorializations of some work, inspired this digressing and imperfect article (also, an imperfect proof of my point).

She was probably hinting at the one risk that the very nature of conversational improvisation faces: for it to be interesting and nurturing, it needs to come from people who actually command their craft, so their anecdotes will carry some weight and insight. She has a point, and it happens in a culture that has exploded in recent years: podcasts. What many people crave in podcasts is the unscripted part. Perhaps my daughter is simply telling me, tactfully, that I have to do my homework to be up to the task. Which is, by the way, an ongoing conversation with her, as her artistic side comes more naturally than the parts of learning that still rely on good-old grinding.

Meaningful conversations vs. ranting

Instead of focusing on eloquence and well-rehearsed production, the best podcasts interview people who excel in their field, letting them “think” in the context of a casual conversation. And by hearing such figures search for what they’re trying to say, or hesitate, or change course mid-sentence, we feel we have a seat at the grow-up table and can hear the actual meaty stuff, not mere factual or inauthentic digressions.

But (and here’s the warning for today’s culture), the same format feels like torture when podcast interviewers converse with people who aren’t trying to elevate their conversation but were too lazy to prepare and will rant or say whatever, sometimes for hours at a time. This phenomenon, which today is becoming pervasive, or at least feels like it, is the consequence of many people trying to copy a formula that they know works on them, because they sense how interviews and speeches that feel like conversations are really engaging and nurturing. As long as they have something to say and are oriented to someone’s insight in some field. Otherwise, it becomes a race to say whatever on whichever field (a bit like the universe of TikTok “experts”).

So my teenage daughter is perhaps trying to explain a self-evident realization for those consuming pop culture nowadays: not everybody can do it. And some people do it effortlessly, exceptionally well. So I’ll go with one example that works for all because it isn’t historical, artistic, or literary: it’s shocking not to see the way Steve Jobs prepared Apple keynotes, but the way he answered low-balled questions, or the off-camera conversations he had before and after interviews, or the few informal speeches to co-workers early in his career. The prepared parts were good; the unprepared parts were at a far higher level.

I’ll try to tell her that I’ll prepare and will work really hard for the lecture we were invited to. Though this effort won’t be oriented to saying things by heart. On the contrary, I’ll try to convey that, by knowing stuff about my trade, I can improvise more freely and perhaps add more “value” by sometimes talking big picture, or sometimes choosing to go on and tell one anecdote that might feel like a good parable to illustrate one point, which is something that we humans are wired for, as our poetry, epic stories, and sacred texts prove.

Risks of parroting written text

As long as you know you’re trying to explain something that has a value, rambling a bit may be more productive than delivering some perfectly polished platitude that feels like a cheap sales pitch, AI slop, or worse: the jargon of a politician playing safe as he dissolves like a sugar cube inside his empty suit. Fruitful, conversational improvisation doesn’t equal ranting, let alone the chatty ramblings of people under some sort of substance influence.

As humans, we have thought about the tensions between formality versus improvisation for a long time, and what’s perhaps one of the peaks of Western culture, the art, plays, and philosophy of Pericles’ Athens, emerged from this very tension. Sophists first and later Socrates (also considered a sophist by many, though “sophism” evolved almost like a derogatory term akin to charlatanerie later on in Classical Greece), didn’t think that formal knowledge fixed in writing was inadequate in nature; however, they also realized that fixed words couldn’t respond, and so memorized speech carried little new value. Robert M. Pirsig brilliantly made the case for sophists and for the value of engaging our knowledge with our lived reality in his surprisingly timely book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, a recommended read for anyone trying to imagine what AI will do to our thinking.

In Phaedrus, Plato imagines his master Socrates explaining why he didn’t want to commit his insights to writing. Like an arrow piercing the wind (or like those famous slow-motion bullets depicted in The Matrix to show how Neo had learned to dodge them), Socrates considered his thoughts dynamic and, therefore, subjected to revision and change by design.

Thought, in motion

Michel de Montaigne, to whom we credit the modern essayistic style of writing, repeatedly warned against the risks of learning by heart, favoring instead digression, contradiction, and a way of thinking that we could compare to jazz in music: thought-in-motion.

That said, thought-in-motion doesn’t equal saying whatever or vindicating B.S. as the new panacea. Of course, not all “improvised” talk is worth listening to. When drunk or high, people cross the event horizon of making sense, and their chattiness gets self-destructive, a non-factual slop that could rival AI hallucinations. Up until recently, many of us feared the crazy-uncle part of family gatherings, for these days, conversations can derail easily. AI has replaced the crazy uncle part and entered our collective unconscious, to the point that it shows up in family conversations and stand-up jokes. But the topic is not as funny as the testimony of our times.

Sitting at the table during the holidays, many will have the curse or the privilege to talk about how people are using AI tools and how much of the tasks we perform regarding language have parallels with the question of form vs. substance.

Many argue there’s growing substance in AI, and I’ve seen the tool evolve as I’ve used it, but one part of the AI zeitgeist that especially interests me. That is: what I crave in human work and interactions has to do with improvisation and the one-off performance part of thinking, or of doing art. If we were talking about music, AI would be getting better at reading musical scores, interpreting them flawlessly, and even making what sounds like improvisations from them. But it won’t be Charlie Parker-playing-jazz level, nor will the sound feel like a one-off battle against one’s own demons.

What we think we want vs. what we need

In abstract, we think that what we love about movies, or literature, or art, architecture, etc., is the ability to create something flawless, smooth as marble, pitch perfect. But we are very mediocre at assessing what truly captures our attention and makes a real, lasting impact on us.

Consider, for example, the difference between college professors who give lectures one can find word by word in the program’s written material (preachers preaching as if they were delivering a written homily), and those who enter the class feeling that they’ll risk everything they know to try to push the conversation so the people attending will grasp a part of what they are feeling, reading, doing in their days. There will be more digressions in those classes, but also an opportunity to reach a higher level of learning that comes from thinking and reaching make-or-break moments in which the audience is a part of the thinking.

Of all the talks and speeches that I’ve ever attended, the ones that really stuck with me and made a real imprint were the ones that avoided everything I find in the endless AI summarization of people and their work: in those AI summaries, I see a dry, factual, sometimes clever synthesis of somebody’s life or work, but those summaries never grasp the movie you watched or the book you read. Instead, what I cherish are the moments when the person you admire gets in the ring and improvises, leaving sentences hanging and offering their powerful vulnerability, their humanness.

That’s why the best moments in stand-up comedy come when some skilled performer ditches the script, and one feels that he’s walking the fine line, willing to risk the night to make it great, or bomb. Working things out in front of the audience is all about reading the room and making the audience an integral part of what’s happening. It’s a self-reinforcing, bi-directional phenomenon that explains why some concert nights or speeches feel so special.

We’ve all experienced this, and perhaps favor formats that feel more “real” because we sense the value in seeing talented humans take risks and think, improvise, before our eyes. AI can’t have the pathos and charisma of a skilled human, nor can it explore an interesting topic or summarize an entire phenomenon with one striking event or anecdote from its own life.

There’s one caveat, however: events that feel fresh and improvised require people we can benefit from, because they’ve mastered their trade and so their perception of the world is relevant and can’t be easily replicated.

Live: A new song out of every old song

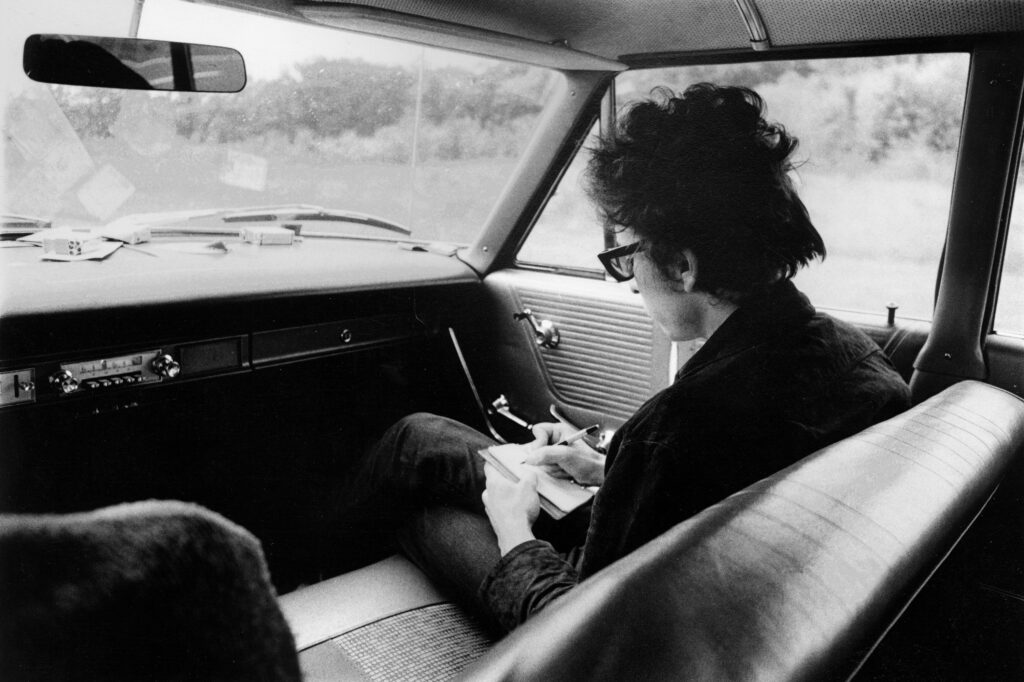

Anybody (not to talk about AI) could replicate more or less the way Bob Dylan sings, and even make a funny SNL-style parody out of it. But they won’t get to the actual “value” of a Bob Dylan event, because the “real” Bob Dylan will often refuse to play the song right. As a fan of the artist, one can feel entitled to feel furious when Dylan decides on the go that he’ll modify the pitch and some of the words of whichever song he’s playing. But many value it and understand that, by rearranging his songs, changing phrasing, and even making them barely recognizable, Dylan is telling them that he’s still “alive,” and he isn’t parroting something that happened in the past. He isn’t repeating meaning, but testing what he’s feeling and how he’s feeling.

It’s no surprise that a memorized talk is the equivalent of playing a hit exactly as recorded, or of replicating a classic painting masterfully. There’s skill in it, but little to learn from a copy that adds nothing else but mere reproduction. (Sometimes, though, as it happens with songs, we listeners compensate for the limitations of a perfect, fixed reproduction by seeing new things afresh each time we reproduce one song or album. We may stop at the lyrics, or understand them in a different way depending on the day, or after we undergo a certain experience, etc.

I invite you to do an experiment: check your local venues and try to attend the next book presentation, or speech event by some person you admire, it doesn’t matter which discipline or impact; it can be a local figure, or universal, somebody just starting, or a consolidated author looking from the retrospective vantage point of having all the great works behind and none ahead. There will be moments, and there will be very formal moments, where things will be said and read, and everything will be very pleasing and up to the etiquette of the person and moment.

Nonetheless, this part (typically the opening third of such speeches, interviews, roundtables, workshops, etc.) will feel bland and predictable, and you’ll see people barely holding their attention. On many occasions, you’ll see people trying not to yawn, and then the yawn begins to get contagious, as well as people staring into space, or secretly sliding out their phones and glancing at them furtively in their laps.

The craft of the interview

There are also events that stay engaging from beginning to end, though they are rarer, and most of them are well-conducted interviews that feel fresh, high-stakes, at times uncomfortable, and always a bit improvisational. But all of these events, no matter their scale, share a common trait—the part that always feels most interesting starts when somebody announces the “formal” event (read predictable, bland) has ended, and the moment comes to moderate a few questions from the public. At this moment, take a look at the audience, and you’ll realize that nobody is blinking.

Memorization has some value, but it lulls us to doze off. Conversely, any event that stays within the formalities of etiquette and platitudes makes us as uncomfortable as a little boy trying to keep quiet during the sermon at a wedding. It can be really dry, even if sometimes talented and charismatic people overcome such moments and inspire others. There’s also that: we’d listen to what some people have to say even if we lived underwater.

When someone recites, they are retrieving information (like a computer, like an LLM), not thinking ex novo. And we, the audience, can notice. If you see a lecture by an artist or a writer, you may already know their work, so you want to hear the human parts: how the work changed their minds, what surprised them after publication, how it was before they were recognized, what the challenges and contradictions of their life and work were, according to them… There are many, many things we’d like to hear about the person who did something that touched us in some way.

Memorization and formality are ways to flatten risk, and the audience feels the lack of stakes in that kind of politician’s trick, tuning out. By contrast, a live talk conducted by someone willing to say things with substance feels like climbing without a safety rope: thoughts can go sideways, anecdotes can open new doors, and questions and doubts can reframe the whole premise. Something polished is far from being the most nurturing thing.

Editing in motion

When we go to such places, perhaps what we seek is presence instead of a perfect pitch, or the parroting of an LLM-grade discourse. Many politicians have historically exploited this fact, and some still do. If memorization values “not forgetting,” playing safe, or not deviating from someone else’s plan. This is probably what people may hate most about public people.

Of course, many things can go wrong when we don’t prepare and improvise. But if we know the topic we are talking about, there’s no greater gift than engaging in an intentional conversation to learn from the audience in real time, as they get inspired and ask insightful, difficult, or wacky questions. The fear of blanking out or being seen as flawed should paralyze us.

If we could only internalize that preparation isn’t memorization or on-the-fly summarization of complex texts and ideas, the world would be even more interesting.

What I like about Kirsten’s editing style is her ability to let people express themselves in their own medium, the way they casually excel at it: nothing is rehearsed, prepared, repeated. When we connect with someone at the other end of the conversation, the sparks we create can be contagious—and nurturing.

Novelist David Foster Wallace was interested in the craft of language to the point of obsession, yet he was deeply suspicious about conversations, speeches, or lectures that felt over-rehearsed. I can see why; he also loved tennis, a sport marked by dynamism, much as the philosopher Robert M. Pirsig explores in the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

Not surprisingly, his widely shared Kenyon commencement speech works not because it’s polished and memorized flawlessly, but because it’s engaged with the moment and understands, “feels” the audience. He pauses, he corrects himself, he rephrases a sentence mid-stream… And we’re hooked.

Like Cézanne’s “ceci n’est pas une pipe,” the best sales pitch happens when we aren’t trying to sell anything and talk from the bottom of our soul, delivering knowledge and craft in the raw.