Thomas Edison defined discontent as the first necessity of progress. Optimism and progress are naïve constructions of non-conformists who believe in a future that can house an incremental change for the better. Non-conformists are the canary in the mine of societies getting ready to avoid disaster, the itch that moves things forward and prevents cynicism and fatalism from taking over ingenuity.

Instead of inhabiting the past like a dark, tormented Joseph Conrad character (Apocalypse Now‘s Colonel Kurtz-style), optimists propel themselves into the future with the determination to prove their own ideas and artifacts. They do so even when they are conscious of their limitations, among them their own fragility.

To an optimist, for a society to thrive at a civilizational scale despite systemic threats, it needs to remain open to critical inquiry and unafraid of experimentation so old models get improved by new ones via trial and error. To theoretical physicist and author David Deutsch, progress as the most critical existential attitude any society can foster: “Optimism is, in the first instance, a way of explaining failure, not prophesying success. It says that there is no fundamental barrier, no law of nature or supernatural decree, preventing progress.”

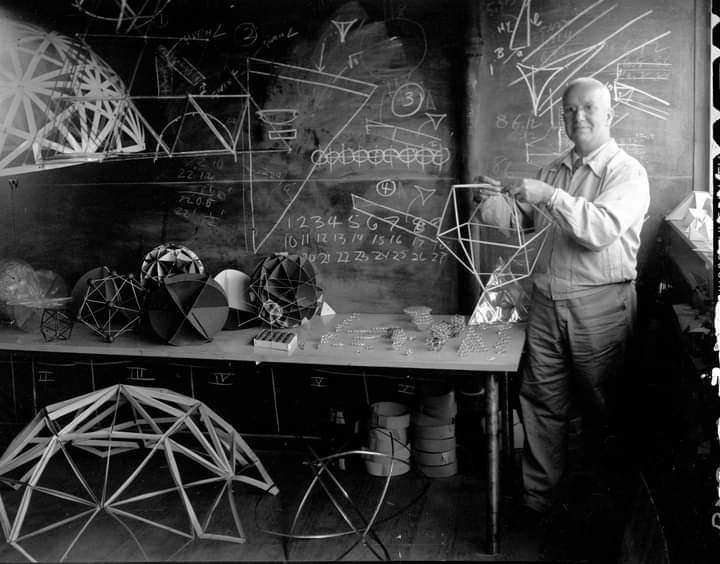

From New York’s car-centric Futurama to Bucky Fuller’s Spaceship Earth

Homes turn out to become “life-changing” when they prevail as places that balance beauty and utility and are patina-friendly, gaining a timeless character as they adapt to host the people inhabiting them, keeping them healthy (and safe). Some celebrated styles come from vernaculars that emerged as a response to previous environmental challenges, social tensions, and even individual or collective trauma: drought, pandemics, forced migration, or destitution. Sometimes, even Dantesque disaster fosters the willpower and ingenuity needed to set conventions aside and experiment boldly. The devastation of wars, for example, prompts architects and designers to build easy-to-deploy homes for the unhoused.

Like the car-centric society displayed in Futurama, the New York’s 1939 World Fair that advanced the vision of a society dependent on superhighways, futurist Richard Buckminster Fuller wanted to build better and faster. The annihilation potential of nuclear warfare had opened an existential threat too significant to spend all energies in parochial discussions: Earth deserved common goals as a very special “spaceship” in space that had allowed life to thrive.

Undeterred by conventional shapes, materials, or layouts of homes or cities, Fuller combined the metallic fuselage of modern airplanes with designs from nature to come up with round shapes capable of self-reinforcing themselves with the minimum amount of material, like the geodesic dome. Fuller played with the concept of tensegrity, a design based on components reaching equilibrium as opposing forces, multiplying their strength. He envisioned it by studying nature just as any kid would have tried to do out of crystalized curiosity.

We had not conceived the scale in which Fuller wanted to innovate until we visited Montreal’s Biosphere, a spectacular 20-story-high spherical structure of steel polyhedrons he built as the American pavilion for the city’s Expo 67. Initially, the structure had been enclosed in a translucid skin of acrylic panels, lost in a fire during repair work in the mid-seventies. Now sheltering a museum dedicated to the environment, the Biosphere is still a civilization-scale type of building that makes anyone wonder, regardless of age or background.

Summer insects in Canada’s lakes

As usual, we had flown into North America to spend several weeks traveling and visiting family in across different locations, reaching the San Francisco Bay Area after countless adventures, some weathered look, and a lot of insect bites. We started in Montreal after finding a convenient ticket from Paris. The morning we approached the building, we wondered about the links connecting Fuller’s biggest built geodesic dome with Gustave Eiffel’s tower. The latter had also been built for a World Fair and remained after its closure despite the controversy and the city’s countless detractors.

For one, said our youngest kid, the Biosphere didn’t feel “pointless.” “What do you mean by ‘pointless,’ I asked.” Well, it’s also sort of fancy, but it wasn’t built to be the tallest thing in this place. It sort of makes sense. “A building covered by a spherical mesh makes sense to you?” “Of course. Bouncy balls make sense.” It looked natural, one of our daughters agreed. “Like a giant dandelion.” We had found the ultimate image of Buckminster Fuller’s protective enclosure. Only it wasn’t our occurrence but a deep, sometimes intuitive study the American polymath had himself pursued to come up with his super-lightweight and structurally sound domes.

Like Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, known for his whimsical, nature-shaped modernist buildings in Barcelona, Fuller had sensed that some designs in nature, like the shape of some plants, could carry weight efficiently. The “tensional integrity” of dandelions allowed them to keep their structural shape despite their lightness in strong winds to accomplish the plant’s dissemination goal.

But Fuller’s gigantic Biosphere geodesic dome in Montreal was also part of one vision to protect human habitation from perceived threats in the midst of the Cold War: home and city shields could help maintain self-regulated environments amid a changing environment. The era’s retina was still staring at the Apocalyptic ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombings when the Cuban Missile Crisis had frozen the world for a moment in 1962. But, in the years following, only the counterculture would seem interested in applying the “tensegrity” of geodesic domes into housing.

Four decades after Fuller’s death, geodesic domes remain among the proposals to cheaply create self-enclosed environments capable of maintaining a controlled atmosphere in their interior that would, for example, help regulate weather and air pollution, as well as speeding plant growth. A Danish team led by Kristoffer Tejlgaard and Benny Jepsen created a few years ago the Dome of Visions, a CNC-cut wooden home inside a self-enclosed geodesic dome acting as a greenhouse. The dome serves as the controlled “outside.”

When in Montreal visiting the Biosphere, we didn’t know then the summer of 2019 would be the last one before a pandemic would take over daily routines and halt the ability to travel. In Quebec, we visited remote lakes with spots only reachable by kayak. Everything in Boreal North America looked as if it had been set at a higher intensity in the summertime, and even the relentless flying insects didn’t seem to belong to the reality we were coming from; their busy activity accelerated to pack existence in the short summer season.

It took us some time to descend back into a world connected by highways and commerce routes such as the one that had opened the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean through the mighty Saint-Laurent, St. Lawrence River. Driving down from the river’s verdant northern shore, we understood how the area had been once a strategic entry point to reach the interior of North America, as lakes, plains, and the Mississippi basin expanded like an interconnected, gigantic valley from Ontario to the North to the Gulf of Mexico to the South, from Appalachia to the East all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

By the Great Lakes’ shore

The area’s old industrial mighty had already vanished; for days on a row, we witnessed the consequences of the demise of steel production and other heavy industries across the border and along the Great Lakes. No wonder strong winds developed into big storms of dust and rain across the Midwest and Great Plains.

We wanted to visit the Henry Ford Museum outside Detroit; our interest wasn’t cars but one man’s dream to manufacture homes with the precision and convenience of cars or appliances. We didn’t have any problem spotting Buckminster Fuller’s round, metal-clad Dymaxion home from afar. The designer and futurist began in the 1920s by drawing a lightweight, prefab home that could be flat-packed and shipped worldwide. Any resemblance with Airstreams wasn’t a coincidence, as recreational vehicles and prefabricated homes experimented with the strength and aerodynamics of modern airplane fuselage.

The Dymaxion (“dynamic maximum tension”) was a concept of the times and included both a home and a car resembling future vans such as the iconic VW T1. Lightweight and sturdy, it was made of aluminum and plexiglass, weighing only 3,000 pounds (1,360 kilograms), less than many cars from the times. The self-enclosed services around the core of the circular layout allowed for little maintenance, whereas the structure could be heated and cooled with natural ventilation, thanks to a vent opening on the dome’s oculus. The circular, prefabricated home was never mass produced, though some of its proposals, like its aerodynamic design, could have prevented damages across the Mississippi basin, especially prone to extreme weather forming in the Gulf of Mexico.

Down south, in the Caribbean, Taino people had learned to bear the damage of hurricane season by building round homes with a 30-degree sloping hipped rood, usually on stilts, a vernacular design template not far from Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion, also a house design intended to prevent destruction.

But avoiding destruction, or entropic acceleration, has not yet reached mainstream status. Scientifically, entropy, or the tendency of things to decline into disorder and heat, is the main suspect physicists quote to explain why time is irreversible: we are heading in just one direction, from the past into the future. In human terms, the irreversibility of the arrow of time translates into cellular oxidation, which sets the clock of our time in this world. Hence our regret in not being able to consider how precious some experiences are, which we will come to appreciate well after they are gone for good.

But what older generations can perceive as a context of chaos, noise, and media fragmentation, is what others have experienced all their life. Learning to make one’s own patterns out of apparent chaos is what distinguishes—some argue—those who can still bring authenticity to a world of dematerialized objects and experiences.

Amateur machinists inside a steel factory carcass in Oakland, CA

The ratio signal vs. noise also appears in architecture, as it happens with the superficial, sometimes cyclic memes on the Internet. And, as happens with information, the most engaged social media users represent extreme visions of urbanism and have antagonistic views of art or even the concept of beauty. Those interested in boundless experimentation, and those depicting modern architecture as the root of Western decadence, argue with the energy of gamers or tech fanboys.

In this case, correlation can explain at least a bit of causation: self-defined advocates tend to be more vociferous. Take, for instance, the world of small, humble dwellings, from code-compliant modern prefab homes, often modern and experimental-prone; and the companies and DIY enthusiasts opting for a reduced version of traditional house designs, a dichotomy between modernity and tradition displayed in the new Accessory Dwelling Unit market across the US States that have legalized backyard cottages in plots in single-family zoning neighborhoods.

Some people interested in tinkering and boundless experimentation in the digital and industrial worlds are trying to improve construction and affect how dwellings take care of people and places. Influenced by informal desert gatherings such as pop-up villages for land sailing, the Burning Man festival, or their own compass, they turn industrial-era materials or leftovers into solar punk or post-apocalyptic dwellings from rusted shipping container dwellings to modern homes made from car and other post-industrial scraps.

One of the travels we will not be able to plan for the future is paying a visit to Kowloon Walled City, the chaotic, impossibly dense, superorganism-like informal settlement that thrived between colonial Hong Kong and mainland China. Such a post-Apocalyptic citadel once concentrated 50,000 residents in 2.6 hectares (6.4 acres, or less than 4 football/soccer fields. A magnet for counterfeit fabrication and organized crime. It was demolished in the mid-nineties.

Bottom-up experimentation

The vertical chaos, paths at different levels above the ground, and impossibly narrow alleys seemed out of the fantasy depiction of Yemen’s “New York of the desert“, only the buildings weren’t made out of mudbricks but an impossible mix of old construction methods with materials coming from the complex post-industrial era detritus. Such an order-out-of-total-chaos approach loses some density and takes a different shape in Spielberg’s film adaptation of Ready Player One, the sci-fi novel: informal settlements out of wildly stacked shipping containers.

An Internet search today will provide with an avalanche of shipping containers, the symbol of contemporary supply chains, reconverted into dwellings, but the first stories we covered years ago caused an impact among unaccustomed watchers. An architect in Lille, North of France, had been converting industrial elements like greenhouse hangars and shipping containers into homes, including his own, for decades. Still, it was social media sharing that turned an oddity into a trend.

When we first saw several shipping containers creating a family home amid second-growth redwoods in the Santa Cruz mountains, we knew the time for post-industrial experimentation had begun to some architects and enthusiasts of what some people have called a “post-Apocalyptic” aesthetic, something out of a Mad Max sequel. But Kam Kasravi and Connie Dewitt didn’t seem to be looking for a “house of doom,” they just had liked the proposal of a home made of several shipping containers assembled on-site in 6 hours, even though they had to be stacked to fit between Redwoods along with a steep grade.

In the early 2010s, we realized the use of shipping containers in construction didn’t make much sense to some architects, structural engineers, and urbanists: could a commoditized, standardized, almost anti-vernacular metal box that had been created to ship goods overseas, be reused as a building block? Soon, shipping container homes, offices, and even apartment buildings began having their enthusiasts but also detractors, sometimes as belligerent as the army of OSB —the cheap wooden composite material to create particle boards using an often-toxic synthetic binding— haters.

Containertopia: post-industrial communities

Not far from Santa Cruz, in the old carcass of the gigantic American Steel factory building outside Oakland, people of different ages and trades had rented spaces to work on personal projects and new artistic or professional endeavors. In the early ‘2010s, the place kept its fresh maker allure: steampunk was appealing, maker spaces, workshops dedicated to machining, and fab-labs were popping in old reconverted buildings across the world, and Bay Area fans of Burning Man had the feeling it was their chance to live under one massive maker space like a business incubator for quirky, highly idealistic and manual endeavors.

We first met Luke Iseman at the space he rented inside the reconverted American Steel factory, but not long after, he had moved across the road trying to bootstrap a techno-agrarian shipping container little village in a residual industrial lot with no services, though Luke Iseman and Heather Stewart saw their setup as their potential “containertopia.” Other examples of shipping container architecture sprouted all of a sudden everywhere, from apartment buildings in New Haven to off-grid homes in the US West high desert or the Australian Outback.

We would meet Luke and Heather at least once per year, and they soon shared with us the complexities of trying to bypass strict zoning laws, even in a visibly degraded mixed-use area of Oakland screaming for opportunities for regeneration. Each time, Luke and Heather would come up with ideas to try to create their own housing utopia, which attracted young professionals unwilling or unable to pay high rents in San Francisco.

Ingenuity and experimentation don’t go hand in hand with an institution of wealth allocation as important as the housing market, yet innovation is accelerating in the low-end of the housing market, where victims of destitution, young idealists, entrepreneurs, technology, and traditional real-estate investors try to find common ground to translate experimentation into realistic, often creative proposals to improve housing.

Reusing factories: sometimes, function follows form

In a little over a decade, pioneers building all sorts of dwellings reached a global audience of people searching for life-changing dwellings and better lifestyles, even when their search process through trial-and-error would yield dubious outcomes.

Studio Ghibli creatives would struggle to differentiate some videogame or movie sets such as the shipping container informal town of Ready Player One and some of the most experimental homes or communities Kirsten’s channel has ever featured. In retrospect, the house that Karl Wanaselja and his family built in Berkeley, shingled out of car roofs and Dodge Caravan side windows, completed with a shipping container architecture backyard studio over a decade before ADUs were normalized in California, looks like a realistic move. It was controversial and “very experimental” not that long ago. Things can change, even in societal perception and zoning law.

Building with salvaged materials and post-industrial “leftovers”, as well as legally building accessory dwelling units, are among the methods aiming at newer equilibriums in suburban densification, as well as urban regeneration and experimentation.

Outright experiments will remain testimonies of solo ingenuity. For 20 years, Bruce Campbell has lived aboard a salvaged Boeing 727 concealed in the woods outside Portland. When we visited him, Bruce insisted on the potential advantages of living aboard a retired jetliner, though not everybody is ready to appreciate old passenger aircraft as protective, extreme-weather proof dwellings that could thrive with a second chance that would prolong their usability lifespan for decades, if not centuries.

Airplane homes seem to belong in sci-fi dystopias, though contemporary society is seldom pioneering this type of reuse: in the late eighteen century, facing an increase in war and criminal prisoners, British authorities decommissioned and converted commercial vessels into prison hulks. More recently, architects such as Catalan Ricardo Bofill turned a derelict cement factory into the flourishing headquarters of his studio and family home, which he called La Fábrica. Bofill, who died in 2022, and his studio partner Jean-Pierre Carniaux, sometimes forms don’t follow function; things can also start over, and flourish once more, this time ecologically, out of a post-industrial carcass such as La Fábrica.

What we can do and decide

The current superposition of global crises with local implications leaves no place to hide from those deciding to dismiss our ability to tackle big challenges. The most powerful insight Steve Jobs claimed once in a video interview acknowledging that we can affect the fabric of reality surrounding us by choosing to engage in the world and study how such structures work:

“Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact, and that is that everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use.”

Steve Jobs was no French existentialist, but Jean-Paul Sartre’s idea of our place in the world was no different. We are “condemned” to be free, mainly because we can affect things around us in a decisive way, whether we like it or we feel instead of the angst and nihilism of sensing there’s no divine creation or remote master behind our actions. Looking once at a barman serving him, Sartre realized that the young fellow had two ways of behaving in his projection into reality: one was to let it go and become a passive subject of what the reality around allowed him to do without facing too much discomfort or risk; whereas the other implied to try to influence the surrounding reality in which we’d like to live.

We all are Sartre’s barman and face the choice of, in Steve Jobs’ terms,

“try not Try not to bash into the walls too much, try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money,” or shaking off “this erroneous notion that life is there and you’re just gonna live in it, versus embrace it, change it, improve it, make your mark upon it.”

Beyond the stasis mirage: improving fallible models

To Chuck Palahniuk, author of The Fight Club, the given reality can be crushing:

“You realize that our mistrust of the future makes it hard to give up the past.” The Narrator in the book, depicted by Edward Norton in the novel’s film adaptation, suffers chronic insomnia and internalizes his unfulfillment with the conventional, interchangeable life of relative success he should be happy to incarnate.

As he cannot imagine a feasible way to change his life, he creates an idealist person in his mind capable of fighting life’s conventional presets. In Palahniuk’s book, Violence and angst are a by-product of the nihilism individuals facing fragmentation, and senseless lives feel. Instead of real choices, people have been told to signal their value system and worth by choosing the products offered by the advertising culture that most accurately match their profile. Instead of finding meaning in a trade requiring creative challenges or manual work, they end up justifying the cost of their education by accepting a so-called “bullshit job.”

What if an idealistic vision of a past that never existed isn’t the answer to today’s challenges? Through trial-and-error, utopians such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s disciple Paolo Soleri have built experimental towns and communities such as Arcosanti, the self-enclosed city-village in the Arizona high-desert where Soleri tried to find the equilibrium between individualism and community, between architecture and ecology, hence the name he coined for such idealistic village-buildings: “arcologies.”

Other symbiotic models try to design homes and communities that prioritize wellbeing and integration of home and environment. Such symbiotic models are timeless, and their allure could belong as easily to a long-gone civilization and also would fit as the dwellings of a highly advanced civilization trying to thrive amid the challenges we face in the future.

Moore’s Law for bioclimatism

When we visited the Dome of Visions in Copenhagen back in 2015, its climate-controlled interior seemed to emulate at a small scale what the Earth’s atmosphere accomplishes with our planet. The dome’s wooden structure had a Scandinavian appeal, but its climatic principles reminded us of other idealistic structures created to benefit from the sun while preventing excess radiation: in the high desert of the US Southwest near Taos, New Mexico, a community of idealists had created what they called “Earthships,” self-sustained homes half-buried into the arid environment.

In winter, their glass facade would gather the sun’s energy to heat its interior and grow food. Their design had evolved through trial, error, and adaptation from a design by architect Mike Reynolds in the 1970s; with their back buried against the ground, their Space Western aesthetic conceals a round design that uses post-industrial waste (old car tires, glass bottles, soda cans) in several different technical and aesthetic applications. Buckminster Fuller’s ideas kept inspiring those experimenting with self-reliance in isolated areas defined by extreme weather.

Retired volleyball player Tom Duke had shown us the Earthship community in Taos a few years back, and we revisited once again in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, this time to interview Deborah Binder on what had changed over the years in the design. The models, she told us, had gotten more efficient and affordable, an evolution expected in fields as apparently divergent as microprocessors’ density, industrial production, and productivity.

A philosophy of life

Though the time seems to have come for experimenting with self-enclosed environments to regulate climate, air quality or garden productivity, the homes accomplishing the promises envisioned by pioneers such as Bucky Fuller are but a handful. Just a few hours by car from the temporary place the experimental Dome of Visions had occupied in Denmark, we visited a family outside Stockholm, Sweden, that had successfully wrapped their home inside a greenhouse, reducing dramatically their energy bills —and impact.

Despite the low average temperature in the area in the wintertime, what Marie Granmar and Charles Sacilotto experienced inside their greenhouse-wrapped wooden home was dramatically different:

“For example at the end of January it can be -2°C outside and it can be 15 to 20°C upstairs.”

Sacilotto had been inspired by the early bioclimatic designs of Bengt Warne, who had designed his first Naturhus (Nature House) in 1974.

To Sacilotto,

“It’s not just to use the nature, the sun and the water, but… it’s all a philosophy of life, to live in another world, in fact.”

Pingback: Geodesic domes: the (failed?) dream of living light on the land – *faircompanies()