There’s no older way of showing one’s agency over one’s surroundings than providing our own food from sources that our ancestors would recognize as familiar, especially when we achieve the ultimate alchemy of turning simple ingredients into a healthy, palatable feast.

This is why Michael Pollan’s 2006 nonfiction book The Omnivore’s Dilemma is such an enlightening reading that transformed how a big chunk of their readers consider food: the way they source it, the way they prepare it, the way they cook it, and, of course, the way they eat it. The book is a useful, inspiring evergreen, a staple food for thought.

I read Pollan’s book during the early summer of 2008-ish in California. I remember borrowing it from a small but decently stocked public library in a Sonoma County’s Alexander Valley town, two and a half hours north of San Francisco and about the same time from what’s arguably been the epicenter of the California cuisine, the Berkeley area around North Shattuck and Vine where the term “farm-to-table” became a food movement (there, Alice Waters pioneered locally-sourced seasonal cooking in the 1970s and opened Chez Panisse).

Nobody will ever consider a landscape familiar to me now, the California rolling hills with solitary oak trees surrounded by yellow pastures, as a place to gather some food and prepare some farm-to-table staple capable of enriching the “California cuisine” brand born around Berkeley’s North Shattuck neighborhood (popularized as “Gourmet Ghetto”).

The taste of acorn meal

Those same oak hills looked very different to hunter-gatherers roaming the area undisturbed (perhaps bothered by the then pervasive grizzly bears and cougars) not long ago. Little things could be more “Californian” than an acorn meal served in a steamy mush similar to today’s Cream of Wheat or Malt-O-Meal.

Once prepared and therefore freed from their tannins (substances acting as plants’ self-defense or natural pesticide), previously bitter acorns were an essential food for several California tribes before and after the arrival of Europeans.

I imagine a chapter of a perfected Omnivore’s Dilemma in which the author doesn’t settle with things such as the reputed Bay Area sourdough bread made possible by precious ambient spores that past bread makers keeping one tradition alive, but also walking up a hill and harvesting acorns (between September and November, like other nuts) with the assistance of one friend familiar with preparing them for a meal: washing, then leaching the acorns, roasting and grinding them, and finally turning them into tasty pancakes.

The scene may not be included in Pollan’s book, and yet, until recently, several tribes in California obtained half of their calories from acorns, something that will seem absolutely realistic to anyone familiar with the landscape of the US West Coast and its Mediterranean weather. The trees, often majestic, with their powerful, extended limbs, are everywhere.

A lost tradition shared across the world since Stone Age

Acorns are a nut, albeit most fruits are starchy and low in oil and protein, but, like other nuts, the fruit is rich in carbohydrates, antioxidants, unsaturated fats, and the minerals calcium, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as niacin or vitamin B2, which helps to convert into energy. Humans can’t eat raw acorns, or at least they can’t do that pleasantly and in big amounts: they contain tannins, which give the fruit an unpleasant bitter taste and make it toxic.

Also concentrated in high values in the tree’s bark and leaves, tannins protect the tree from insects and fungi attacks. When ingested by humans, they cause nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, irritate the stomach, accelerate blood clotting, reduce blood pressure, damage the liver, and alter the immune system. In small doses, however, many classes of tannins can be beneficial to humans given their antioxidant properties and effects, lowering the total cholesterol and reinforcing certain immune defenses thanks to their antibacterial properties (for example, tannins from tea, spices, legumes, chocolate, and other sources would fight tooth decay).

According to Heidi Lucero, tribal chair of the Juaneńo Band of Mission Indians of the Acjachemen Nation, preparing acorns required first roasting them to kill weevils, then shelling and grinding the nuts into a flour too bitter to cook and eat right away; to remove the tannic acid, natives would leach the flour, flushing the bitter-tasting organic substances out with water. According to Lucero:

“It is definitely an arduous process. But when you have something that can last through the winter season, it really is worth having that as a food source. It’s something that can be stored. And it’s definitely worth the process of making the acorn soup or the wiiwish.”

She cooks the wiiwish on a portable stove with a bit of water. The flour thickens quickly into a cream. Tribes would eat the plate, resembling oatmeal or Cream of Wheat with meat or fish on the side. Lucero likes to add a bit of salt or honey.

When paradise looks like an oak grove

Southern Europe has also forgotten its deep relationship with oak trees and their bitter nuts. Today, Spaniards relate acorns to the pastorally managed tradition of feeding Iberian pigs with acorns on open fields sprouted with oaks known as dehesas that cover the sparsely populated areas of Extremadura and Western Andalusia. Pigs love acorns, the known tradition in the area states, albeit a less known tradition, now forgotten, links acorns with the diet of stone age Iberian, Italic, and Greek tribes.

Hence California’s tribes aren’t the only peoples who have traditionally relied on acorns to complement their diet thanks to their nutritious value once leached and freed from their tannins. Roman accounts describe peoples from the Mediterranean basin surviving on acorns, including Greek and Iberian tribes at both ends of the basin.

Acorns were a staple food in Celtic Spain, according to Strabo, and Pliny the Elder described how by selecting less bitter specimens that were leached out with water, the obtained flour had the quality grade to make bread from it. At the other extreme of Eurasia, during the Japanese Neolithic (Jōmon period), people would eat acorns in times of famine.

Acorn meal with Racahout please

The tradition of gathering oaknuts for human consumption predates written culture and even the wave of plant and animal domestication that paved the way to the great leap of the Neolithic: rock paintings dating from 12 millennia back found in the Abrigo de la Sarga, a cave in Alcoy near Alicante, in the Spanish Mediterranean coast, shows people collecting acorns from oak trees. Not far from Abrigo de la Sarga, an 8,000-years-old painting at Coves de l’Aranya (Bicorp, Valencia) depicts a Mesolithic honey hunter harvesting honey and wax from a tree honeycomb.

These two Stone Age Iberian staples, acorn floor and honey, are some of the ingredients of a renaissance in Spanish cuisine, which tries to bring back flavors from the past, even if it’s so remote that predates history itself: stews and fritters from Asturias to Andalusia restore ingredients such as chestnuts and acorns, replaced with imported staples rich in carbohydrates that arrived in Europe with the Columbian Exchange, especially potatoes.

Acorn meal isn’t only a forgotten resort from the remote past in the Mediterranean that has left little trace and actual tradition: during the Spanish Civil War and the harsh autarchic post-war years, acorn and algaroba flour were a precious substitute of wheat and other grains.

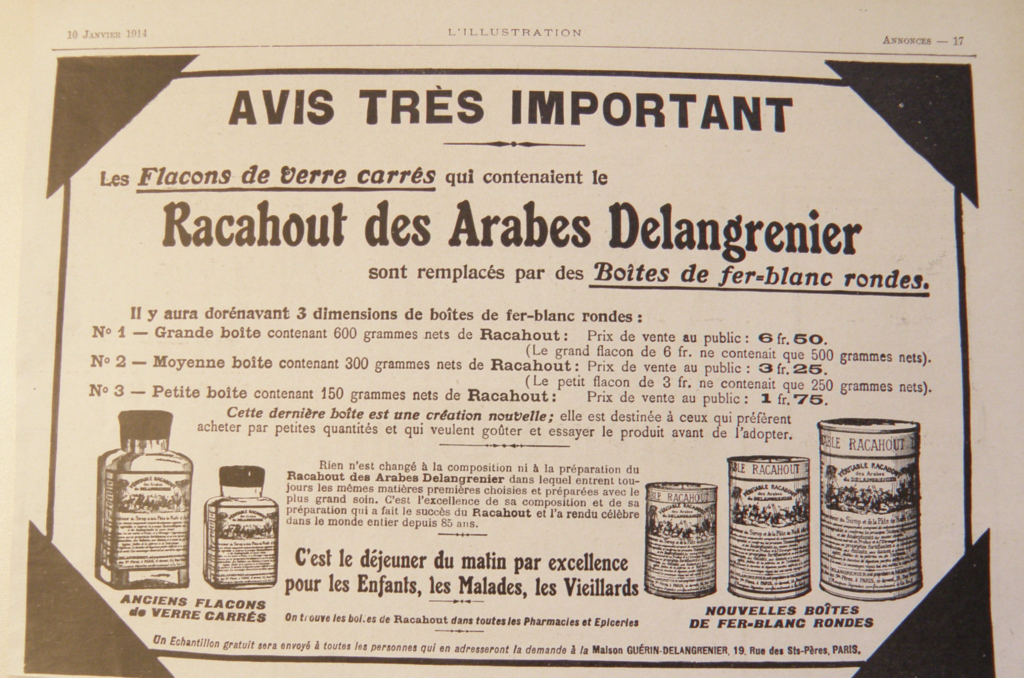

In the Ottoman Empire, people buried acorns for some time to extract their tannins, then dried and toasted them. The powder would then be mixed with sugar and aromatics, an energetic and digestive beverage with a taste reminiscent of chocolate, called palamoud by Turks and racahout by Arabs. Arabian Racahout (“Racahout des Arabes”) became fashionable in nineteenth-century Paris.

Oak: a symbol

A symbol of strength, endurance, shelter, and long life, the oak tree, abundant in different species across Europe, North America, and Asia, bears a fruit borne in a cup-like hat, the “cupule,” containing one seed that, if forgotten by squirrels, woodpeckers and other animals that bury them to feed themselves in winter, turn out to become tree sprouts.

While Parisians could buy Racahout des Arabes, a new nation desperate for new symbols (preferably traced back to Christian references), the United States used profusely the oak tree in its symbology, like the “oaks of righteousness,” planted by God and not by forgetful squirrels. Two of its nineteenth-century spiritual authors in search of a fully autonomous voice, the New England friends Thoreau and Emerson, mentioned the tree metaphorically.

In the Old Testament (for example, the Book of Isaiah, 61:3) oak trees are a symbol of regeneration, a display of strength and of hope planted by God (read “Nature”) to focus on beauty, gladness, and praise instead of “ashes,” “mourning,” or “despair.” Emerson was probably aware of this biblical passage when he saw the potential of the tree’s bitter fruit:

“The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn.”

How oak trees start

Like Thoreau, Emerson was captivated by trees and responded to them like any nineteenth-century intellectual influenced by German idealism and the Romantics, though Thoreau’s transcendentalism aimed at singing North America in particular.

As a naturalist and a writer, Thoreau could portray trees poetically, but also with the ambition of somebody invested in pantheism, or the connection of all living things; there’s no coincidence that naturalist E.O. Wilson (who coined the “biophilia hypothesis“) chose an imaginary walk in the woods with Thoreau to start his essay on conservation, The Future of Life.

Thoreau was familiarized with the white oaks growing around Concord and the pond of Walden, a proximity place nearby he chose to build his cabin; he was capable of admiring the pasture oaks, majestic and solitary in a misty meadow, yet he praised especially the small oaks that try to reach for enough light under the canopy, the shrub oak that could one day give shelter to a passer-by, then already mighty and centenarian. According to Thoreau:

“Every oak tree started out as a couple of nuts who stood their ground.”

Why we never domesticated oaks?

A nut eaten by different cultures across the world, growing from such a symbolic, pervasive tree in temperate regions. We could assume that this relation with oaks would make a strong case for domestication. Surprisingly, it never came, and oaks have remained wild to this day.

Another nonfiction book classic from the last decades, Jared Diamond’s account of how human societies experienced different fates and, ultimately, how Europeans took over the world, Guns, Germs, and Steel, poses a puzzling question: if plant domestication goes back over 10,000 years and, back then, early farmers knew little about variety selection, how come almonds were domesticated and not acorns?

Like acorns, wild almonds were poisonous given their high-tannin content, only almonds would have seemed worthless to our ancestors, given their smaller size. In addition, acorns were prized by Stone Age peoples, as shown in archaeological remains and cave paintings. What deterred our ancestors from domesticating the fruit of the majestic oak, selecting for ever more nutritious and less bitter varieties, and planting the oak specimens capable of consistently yielding the expected outcomes? Jared Diamond:

“What made some plants so much easier or more inviting to domesticate than others? Why did olive trees yield to Stone Age farmers, whereas oak trees continue to defeat our brightest agronomists?”

Guns, Germs, and Steel, p. 115

Humanure avant la lettre: latrines and first farmers

In the early Neolithic, human latrines were one of the “laboratories” or testing grounds for first unconscious, then conscious plant domestication. The seeds growing in such waste spaces near the first high-density populations belonged to plants already selected in the wild due to some preferred traits.

When the first farmers began to sow, they selected seeds from plants they had favored from certain bushes, which led to modern almonds (luscious, nutritive), modern strawberries (bigger, sweeter than their wild equivalents), peas, and many other ancient, domesticated seeds and fruits.

This process never happened with acorns, already beloved by so many human populations worldwide. What prevented humans from selecting less bitter, faster-growing varieties of acorns? Like acorns, wild almonds were bitter, bad-tasting, and even poisonous to big mammals when eaten in high amounts, a natural selection strategy to deter animals from eating them.

Wild almonds contain amygdalin, which breaks down as basically poison to most animals and humans. Perhaps, in the distant past, a group of individuals located tree specimens with a mutation preventing them from synthesizing the bitter-tasting amygdalin. Hungry children or farmers would have spread some of the seeds, consciously or unconsciously, and kept selecting less bitter and better-tasting varieties.

The problem of industrious squirrels

According to Jared Diamond, our ancestors loved acorns. However, they faced real adversities in trying to domesticate oak trees, as they are slow growing and evolved to let industrious animal species spread their seeds, like squirrels and woodpeckers, responsible for forgetting buried acorns that turn into potential trees:

“Why have we failed to domesticate such a prized food source as acorns? Why did we take so long to domesticate strawberries and raspberries? What is it about those plants that kept their domestication beyond the reach of ancient farmers capable of mastering such difficult techniques as grafting?

“It turns out that oak trees have three strikes against them. First, their slow growth would exhaust the patience of most farmers. Sown wheat yields a crop within a few months; a planted almond grows into a nut-bearing tree in three or four years; but a planted acorn may not become productive for a decade or more. Second, oak trees evolved to make nuts of a size and taste suitable for squirrels, which we’ve all seen burying, digging up, and eating acorns. Oaks grow from the occasional acorn that a squirrel forgets to dig up. With billions of squirrels each spreading hundreds of acorns every year to virtually any spot suitable for oak trees to grow, humans didn’t stand a chance of selecting oaks for the acorns we wanted. Those same problems of slow growth and fast squirrels probably also explain why beech and hickory trees, heavily exploited as wild trees for their nuts by Europeans and Native Americans, respectively, were also not domesticated.

“Finally, perhaps the most important difference between almonds and acorns is that bitterness is controlled by a single dominant gene in almonds but appears to be controlled by many genes in oaks. If ancient farmers planted almonds or acorns from the occasional non-bitter mutant tree, the laws of genetics dictate that half of the nuts from the resulting tree growing up would also be non-bitter in the case of almonds, but almost all would still be bitter in the case of oaks. That alone would kill the enthusiasm of any would-be acorn farmer who had defeated the squirrels and remained patient.”

Guns, Germs, and Steel, p. 129

The low tannin fruit

This hypothesis documenting our ancient failure to domesticate acorns makes sense, albeit it all feels like a big, missed opportunity, especially if our intention is to try to combine food production with sustainable practices that could, for example, turn oak-rich Mediterranean and temperate forests into natural areas where harvesting nutritious acorns and pastoral management (of Iberian pigs, etc.) is compatible with human food production.

Large oak groves such as “dehesas” in Spain occupy big extensions of the Meseta, the Iberian central Plateau, and have become key reservoirs of flora and fauna over the centuries. Not far from the Extremaduran “dehesas,” the National Park of Monfragüe hosts one of the biggest populations of raptors in Europe.

Monfragüe hosts the world’s highest concentration of imperial eagles, as well as a large population of vultures, Spanish imperial eagle, golden eagle, and Bonelli’s eagle. Iberian Lynx, a symbol of Iberian wildlife, has been reintroduced in the area.

When it comes to “dehesa” management and the promotion of large oak groves across their natural habitat, are we stuck with leaching acorns, or could we select oak varieties capable of yielding low-tanning fruits?

Pingback: Famine Foods of Europe: What People Ate to Survive Starvation()