Less known than the current enfant terrible of French literature Michel Houellebecq, writer Emmanuel Carrère published an engaging yet painful account of his descent into depression with a suggesting—and very contemporary—title: Yoga (best-seller initially published in France in May 2020, to chill readers amid the first Covid lockdowns).

Carrère sets his self-awareness about his disarray when, in 2017, he receives a journalist from The New York Times at his apartment in Paris for an interview, which he will later read as the mirror of the misery he was feeling back then, living on his own in a gloomy apartment, described by the visitor, Wyatt Mason, as follows:

“Carrère was very much in that fragile state when we spoke. His writerly purgatory was also a domestic one: Of late, he said, he has had the impression that he has no idea where he’s living. He has not been living at home, he and his wife having recently sold their apartment and bought a new one that isn’t yet habitable and that left him occupying an absent friend’s place, one in which there wasn’t the least trace of life, anyone’s life — no books, no pictures, no chosen anything: no nothing — and that had, therefore, a sinister air of vacancy. The vaguely creepy ambience of that objectively pleasant apartment into which Carrère welcomed me — large windows facing a leafy courtyard; two floors — was further amplified by the presence of a huge leather couch at its center, a couch that seemed somehow forlorn, abandoned, a huge dog of a couch waiting miserably for its owner to return.”

Yoga and a black dog

From self-help literature to cognition studies, to Tiktok short clips served by machine learning, few things can define with such precision the search for introspection and well-being in the neurotic contemporary world as the evergreen New Age escapism: no better word than “yoga” to summarize such a book.

Interesting and honest, the autobiography crosses the limits of reality-fiction and enters the realm of what Rob Doyle (in his review of Carrère’s book for The Guardian) called a “self-cannibalisation” memoir.

Unlike, say, Karl Ove Knausgård’s ruminations, Carrère’s memoir is concise and focuses mainly on debunking the author himself, offering a chilling and masterfully written peek into a diminishing, years-long depression that came after a middle-age apex of self-accomplishment, public recognition and financial/marital bliss.

Using the engaging craft that awed critics and readers in 2000 when he published The Adversary (a non-fiction crime novel that reads like a European update of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood), Carrère describes his inner miseries with such craft for engagement that the reader cannot think but the writer’s neurotic exhibitionism, who enters a world of seclusion and self-destruction after having an affair at a yoga retreat. From then on, the reader brazes for more than the collapse of the ego, as the yoga precepts teach by doing. I’ve read both The Adversary and Yoga, marveling at the author’s ability to absorb us in. Yoga is also, if anything else, a personal treatise about what Roman poet called the “black dog” of depression:

No company’s more hateful than your own,

you dodge, and give yourself the slip; you sneak

in bed or in your cups, from care to sneak

in vain: the black dog follows you and hangs

close to your flying skirts, with hungry fangs.

The feeling that there’s no divine masterplan

What does the deeply engaging character of this memoir tell about our times? There’s an abundance of pseudo-formulas to help people become some kind of hyper-achievers, or, as philosopher Byung-Chul Han states, in a society in which the means of production are non-tangible (or even online), “everyone is an auto-exploiting laborer in his or her own enterprise.”

This commercial push to feed our hubris (our “narcissistic ego,” if we want to call it that) benefits from the commerce of unconscious hedonism already detected by sociologist Thorstein Veblen at the beginning of the 20th century. Only now, it’s more acute.

In Escape from Freedom (1941), psychoanalyst Erich Fromm related the rise of depression and disarray in the angst of the modern individual when he realizes that there’s no grand divine strategy for everything and, therefore, we’re masters of our freedom. Emancipation from divine omnipresence, Fromm argues, can cause fear, anxiety, alienation… and all sorts of contemporary ailments and unbalances like the constant need for superficial stimuli to avoid listening to our inner voice, hopes and fears.

Paradoxically, unconscious hedonism and the fall of traditional institutions and belief systems haven’t only exacerbated the so-called diseases of civilization (existential uneasiness and malaise) but also substituted addictive behaviors for immersion in traditions that teach the opposite of the Western conception of individuality and narcissism, like the ego-suppressing Eastern religions and practices, from Buddhism to yoga.

According to Byung-Chul Han, however, the ever-growing diseases of civilization (burnout, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) are only the symptom of an underlying, unsolvable dissatisfaction with life, which feeds the will to fill the void of a lack of solid beliefs with a cult-like pursuit of the last fad, or else. Characters in novels of neo-decadent writers, from Michel Houellebecq to Irvine Welsh, seem to confront their dissatisfaction with cynicism and self-destructive hedonism, as if self-destruction were the only viable alternative to the rat race of keeping oneself busy to avoid confronting fundamental fears.

A writer’s hyper-awareness

In such books, there’s no possible redemption from page one, as if confronting one’s own fears and finding a purpose in life seems something out of a different dimension that the characters are unable to grasp; in that sense, they can’t escape from their own constrained existences and only fall for escapism of some sort —and that’s the difference between Houellebecq’s characters and Kafka’s, who are also doomed but lack the contemporary pursue of anything capable of eluding confrontation with one’s own fears —and one’s ultimate freedom to act upon them.

That said, Emmanuel Carrère is far from your typical naïve individual lost in petty addictions to avoid confronting his inner self. In a way, he’s quite the contrary, somebody “too aware” of his limitations and those brought by that messy thing we call life. However, Carrère will offer little metaphors of his own progress in overcoming depression by dealing with productive examination (introspection), self-flagellating thoughts (rumination), and the negativity and low self-esteem that sometimes spirals into neuroticism.

In a way, Yoga starts and develops as a gigantic exercise of rumination, focusing on why he is in mental distress, explaining what are the causes, and masterfully describing the consequences; but then, as the book speeds towards resolution, we start to see the development of the healing that comes with metacognition, by accepting that things are the way they are but also acknowledging that there are books to write, life to live, and things to improve. People can even learn typing —as Carrère, an accomplished writer who had always tapped with his two index fingers, explains to us.

A life worth living

Are classical Western philosophies of life like stoicism (perhaps, the beginning of No-BS self-help) and Eastern wisdom precepts that encourage meditation (like the ancient spiritual practices from ancient India that inspired today’s Western yoga practices) a way of reaching well-being and transcendence knowing oneself as advised by the old Delphi inscription, or a descent into “rumination,” defined by psychiatrists as the evil twin of introspection?

The rise of individualism in modern societies went along with a rekindled interest in the classics and the praise of a self-examined life, following Socrates’ idealized precepts and warning against the worthlessness of one existence (if lived unaware of one’s own potential for knowledge).

As with Socrates, to whom the pursuit of wisdom is aligned with an ultimate ideal of goodness and self-elevation, modern psychology turned self-examination into a core principle, which inspired, for example, Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. To Maslow, people need first to meet basic needs to pursue a higher level of transcendence and self-awareness.

Already in the 19th century, introspection (a constructive, elevating kind of self-examination) also became the poster child of a conscious construction of the American character by Emerson, Thoreau or Whitman. Henry David Thoreau famously transformed his experience in Walden into a metaphor of living simply and deliberately to overcome the meaninglessness of a life by listening to one’s inner drives and goals, even if that means living in discordance with his neighbors in Concord:

“Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed and in such desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”

Out in the woods

To thinkers like the American transcendentalists, the propensity to live by routine and artificial drives isn’t a life worth living, associating a more elevated existence by rediscovering our inner rhythms and relating them to Nature —and to other self-aware people.

Thoreau was ahead of his time in many respects, which perhaps explains his imprint on personalities such as Lev Tolstói and Mohandas Gandhi regarding the rights of individuals, collectives, and Nature. He also made an imprint in modern psychology, which would explain his popularity across the board, from traditionalists to techno-utopians. Introspection, or self-examination, requires discipline and can be at times arduous, though its potential benefits can change somebody’s life by affecting behavior, self-assuredness and well-being.

Modern psychology relates the “constructive” introspection predicated by philosophies of life with a sense of self-awareness (or metacognition that allows a realistic self-assessment in difficult moments, so we can overcome challenges and even improve upon previous expectations and odds).

But “too much thinking” about one’s limitations and mistakes, or about relative misery versus others, can generate the type of rumination that prevails among people falling into deep depression even when everything seems fine. And, sometimes, not even the chemical disruptors of antidepressants help with the underlying causes of such rumination, seen as the dark side of introspection.

We can read Thoreau’s Walden, or even his 1862 essay for The Atlantic simply titled Walking, as a oneiric depiction of how the author has turned rumination into introspection: walking in the forest boosts a type of cognition that, according to studies, promotes well-being, reducing rumination.

“When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or a mall? Even some sects of philosophers have felt the necessity of importing the woods to themselves, since they did not go to the woods.”

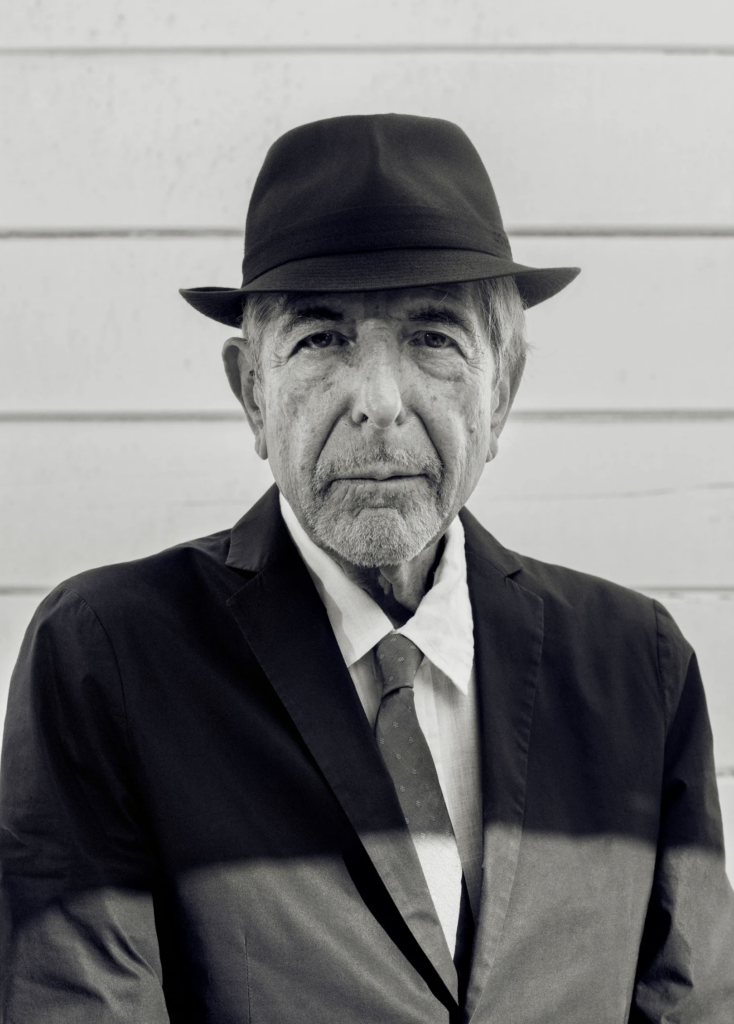

Leonard Cohen on breaking the cycle of depression

If there’s a field where correlation shouldn’t be confused with causation, it is in the links between mood disorders or other mentally debilitating conditions, and creativity. Studies about the prevalence or mental propensities in certain types of artists could lead to the conclusion that affections like rumination, neuroticism or bipolar disorder could aid creativity.

Other studies try to prove that, if sometimes true, such propensities are not the drivers of creativity but the suffering they cause. To some artists, art turns out to be a way to overcome illness or existential angst. Having an elevated purpose (or, in the terminology of psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, finding a “meaning” that drives us), any art of creation reduces stress, anxiety, or depression, helping with coping skills and self-esteem.

Some artists can teach us a thing or two about mood disorders and acute situations. Canadian singer and poet Leonard Cohen struggled with depression and mood disorders all his life, and medications weren’t solving it:

“I’ve taken a lot of Prozac, Paxil, Wellbutrin, Effexor, Ritalin, Focalin. I’ve also studied deeply in the philosophies of the religions, but cheerfulness kept breaking through.”

At times, his episodes were so debilitating that he wouldn’t be able to get off the couch, though, in other moments, he could go about his life despite “the background noise of anguish still prevailed.”

In his 60s, Cohen was releasing successful albums and going through hospitalizations and treatments that led to relapses. After reaching a low point, Cohen retreated from public life and entered a Buddhist monastery, where he was ordained as a monk. There, he argued later, he learned to deal with “the loyalty and the tyranny” of rumination, teaching himself the discipline of constructive introspection.

The tyranny of self-pity

Cohen had it easier than those who didn’t find their purpose or creative passion. To him, the propensity to have dark musings also inspired his lyrics, though he ultimately needed to overcome this apparent benefit of destructive ruminative tendencies by “dissolving them” thanks to the ability he developed to make an honest self-assessment of his situation.

For Cohen, the transformation arrived later in life. It didn’t come with the help of conventional medicine and antidepressants but by mastering “metacognitive awareness,” or being aware of what you think with enough detachment to recognize the parts of excessive thinking that turn against you. Only he called it “Buddhism.”

When Cohen talked about the “loyalty and tyranny” of the negative inner thoughts that kept coming back for decades; that is, until he recognized the intrinsic problem of such ruminations: they become a toxic craving, a way to justify one’s own limitations and or problems.

Breaking this cycle with an honest self-assessment, no matter the name one uses (“yoga” to Emmanuel Carrère, “Buddhism” to Leonard Cohen, “metacognitive awareness” to psychology) is the opportunity for a new beginning beyond the tyranny of self-pity and chronic medication.

In an interview conceded to TV during the nineties after being ordained as a monk, Leonard Cohen, he was asked whether he was afraid of losing his creative ability by overcoming depression. Cohen’s answer debunked what he considered the myth that associate suffering with producing good or insightful work:

“I don’t think that’s the case. I think in a certain sense it’s a trigger or a lever, but I think that good work is produced in spite of suffering. And as a response, as a victory, over suffering.”

Anthem (1992) is one of the few songs in which Leonard Cohen ventures in a melodic chorus, abandoning, if only for an instant, his grave talk-sing. It’s a moment of victory and acceptance of things as they come, for there’s no perfection or total redemption. Like in the painting masters of chiaroscuro, appreciation comes from the little light illuminating the darkest places of the soul:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Leonard Cohen

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.