Walter Benjamin warned that machines would steal the “aura” from art. Between a celebrated old travel-photography archive and every other journey lies another truth: that presence can’t be stored, only lived.

What’s the “aura” of things? Middle-aged people with teenage kids at home have an advantage when it comes to seeing how language adapts to new uses and becomes as flexible as it seemed when we were also inventing idioms. Smells like teen spirit.

From what I’ve observed, when teenagers talk about someone’s “aura” these days, they don’t mean the early Christian depiction of sanctity as a glow around a figure, but rather the vague shimmer of coolness that can be seen through a social media story, or even someone’s charisma.

Cultural critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin meant something in between both interpretations, that of our children and the early signs of sanctity: in 1935, Benjamin considered what mechanical reproduction would do to art expression.

Decades before Andy Warhol, the digital world and the attempt to turn bytes into unique objects through ideas like NFTs, Benjamin imagined a world in which things wouldn’t be unique anymore, and people would not only fail to differentiate between the original and the copy, but the very meaning of what’s “original” would disintegrate. To Benjamin, “aura” was the unique presence of a work of art in time and space: a play, a concert, a painting exhibition.

One century apart: early travel photography and AI loved ones

Aura also has something to do with impermanence. When, as parents, we revive a moment with our children through pictures or video, we try to recapture that moment in time, albeit vaguely, while acknowledging the magic of a moment that can’t be fully revived as it was, not even by the protagonists themselves. A “presence in time in space,” in Benjamin’s words, that is unique. Perhaps art is our attempt to grapple with impermanence, and I’m sure there must be many theories about this.

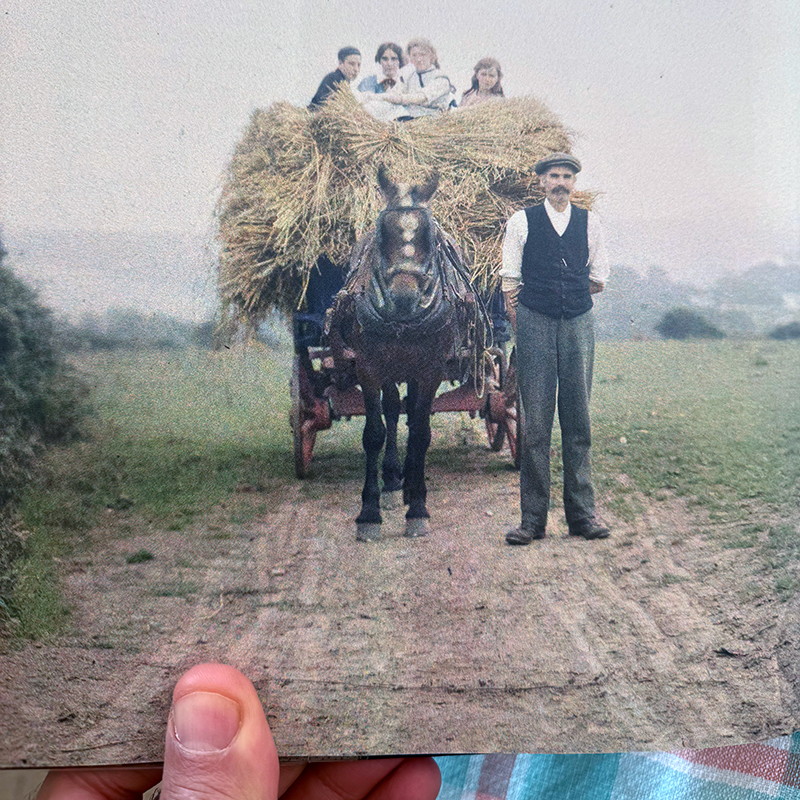

However, at the dawn of modernity, many people thrived during the transition from old to new formats, and early photography was very experimental, much closer to our modern idea of art than it is today. People didn’t smile when posing for a picture, and that’s when they were alive: many times, the medium was used to immortalize the dead, to depict them truly, perhaps in search of some sort of permanent imprint not only of the body but also of the soul. Techniques such as long apertures and superposition were employed to play with movement and a sense of impermanence.

Death photography was indeed an unsettling art, and we could trace one contemporary technological analogy to how it felt for common people to have their recently deceased loved ones photographed, sometimes surrounded by people and with their eyes open, imitating their former selves.

As AI evolves, many companies are improving their very particular LLM models: trained with information of deceased people, such AI personas are activated to remind relatives and loved ones of a painful loss. Like the people in early formal pictures of the dead, those who think of AI as a means to recreate souls are embarking on the very human endeavor of grieving.

When cameras went compact and affordable

Early photography rapidly became more widespread, especially after the invention of film and the launch of the first affordable compact cameras. When George Eastman unveiled the Kodak No. 1 in 1889, it popularized roll film (which many of us have used extensively but know that our children haven’t), and it changed the way we take pictures and see the world, allowing early photographers to travel more freely.

Years passed, and the early black-and-white techniques evolved into color. Photography seemed the medium poised to immortalize things realistically. It didn’t capture reality, however, just a moment in time. It was up to the photographer to preserve the “aura” of the scene depicted, the context, the people and their worries, hopes, and conceiled aspirations.

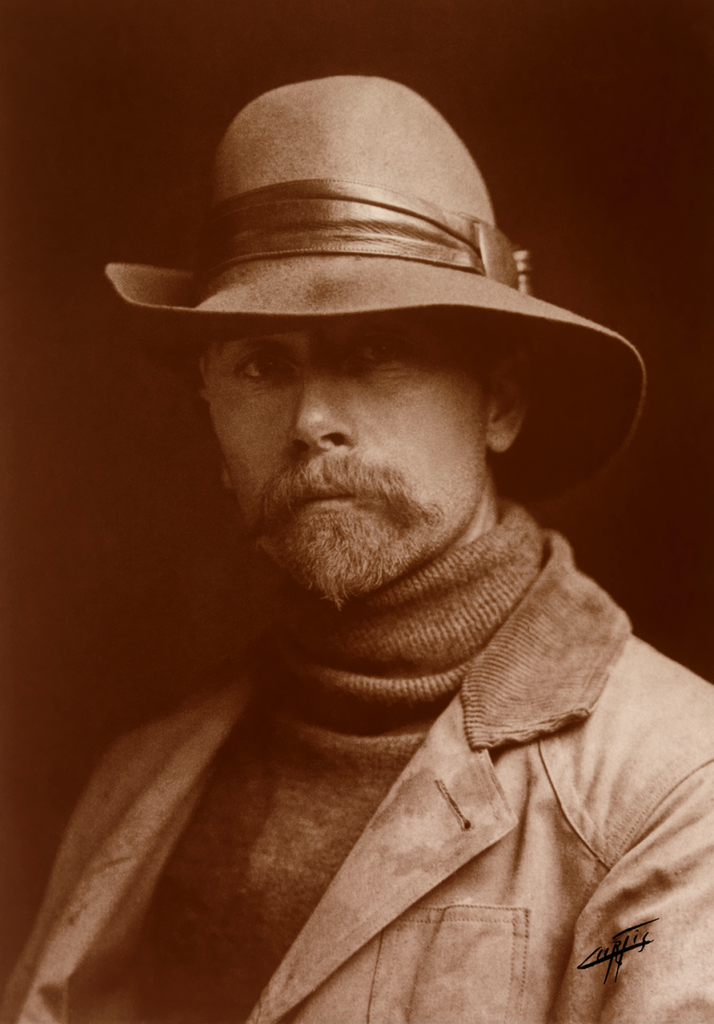

Some enthusiasts of photography’s potential went beyond what was expected of them and realized that many realities were vanishing in the world: landscapes, peoples, and situations. In the vanishing American Frontier, native Americans were forced out of their historical land, language, and customs, and it was happening fast. So fast, indeed, that Seattle-based photographer Edward S. Curtis decided to document a world of traditions, costumes, rituals, and relationships to the land across Native American tribes in North America.

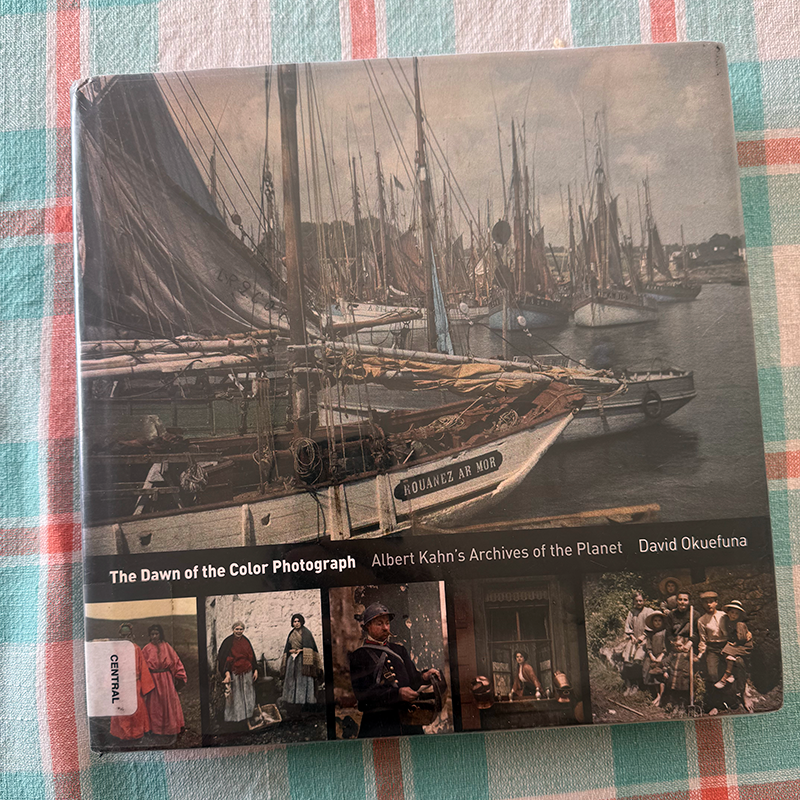

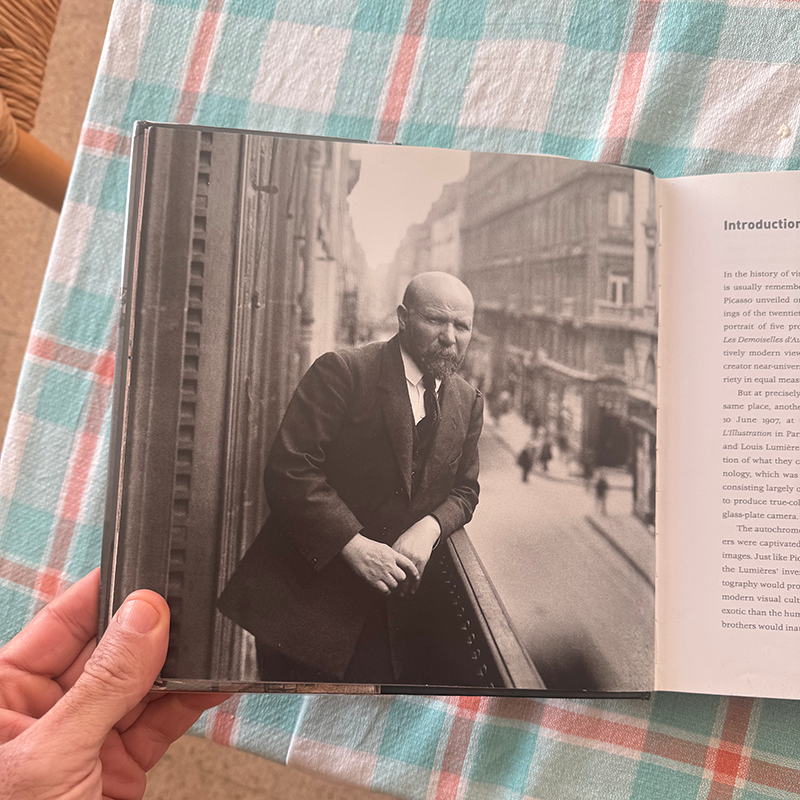

In Europe, a Parisian banker named Albert Kahn decided to invest his fortune in a Quixotic quest to preserve the aura of reality in a world that was vanishing as quickly as Native American customs with the advance of industrialization, modern communications, and Western interests through colonization.

How to capture impermanence

Albert Kahn had had success and, as he entered maturity, he got tired of a simple pursue of the things a man of his rang may aspire to: a delicate and extensive property in Boulogne-Billancourt, the aspiration of having a street, perhaps an important avenue or building named after him in the City of Light; a villa in Southern France and getaways in Bretagne, and Cornwall, England; a good deal of meaningful charitable work; perhaps political influence?

To Albert Kahn, however, this wasn’t enough. Curious about what he had yet to discover in life, he began a world trip in 1908/9 that brought him all over. What Kahn had seen as a young man during the transformation of Paris by Haussmann, which tore apart entire sections of the medieval grid of the French capital to lay out rectilinear boulevards to rationalize (and hygienize) the city, he was now seeing all over the world: soon, particularities of landscapes, vernacular architecture, peoples’ outfits and traditions would give way to standardized experiences, clothing, dwellings, language, food.

Albert Kahn was self-conscious that he was a part of the modern world taking over the rest of reality, shaping landscapes and people. So, he launched his most ambitious philanthropic quest: to capture the aura of disappearing natural landscapes and human realities, using photographers who would travel across the world to create an “inventory of the surface of the globe, occupied and organized by man as it presents itself at the beginning of the 20th century.”

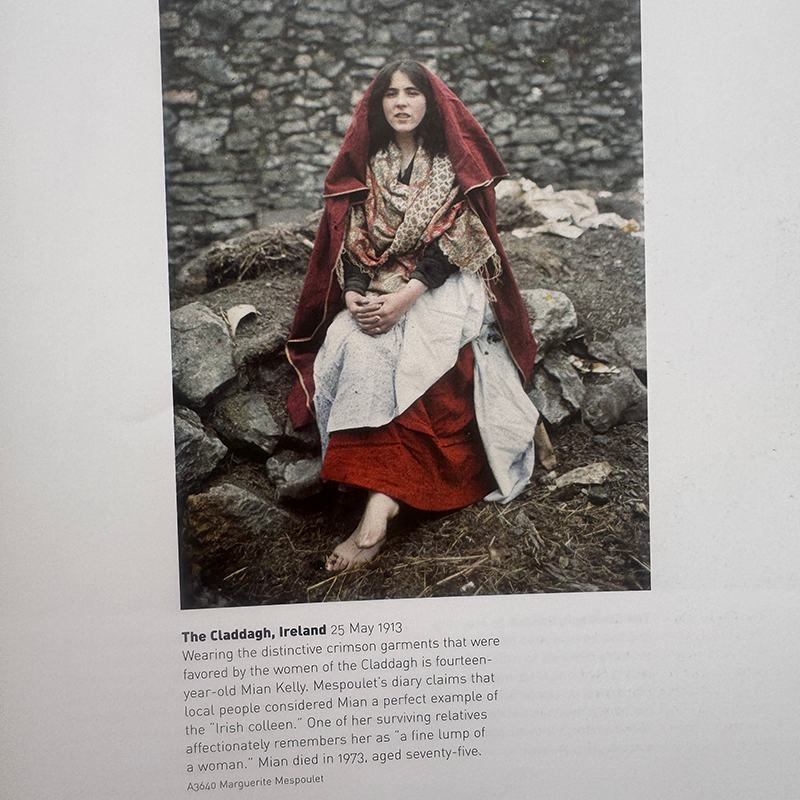

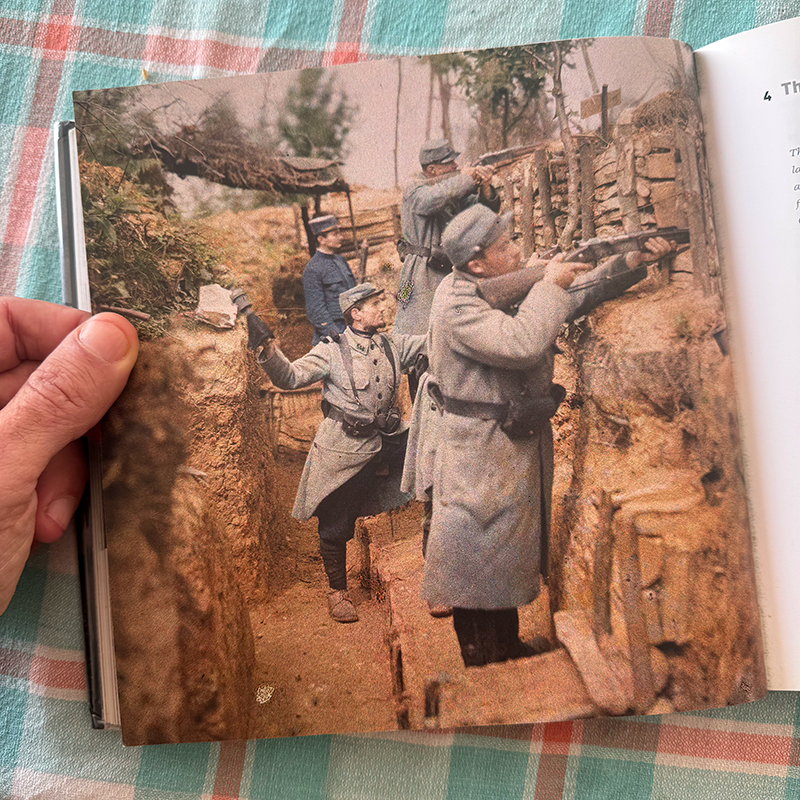

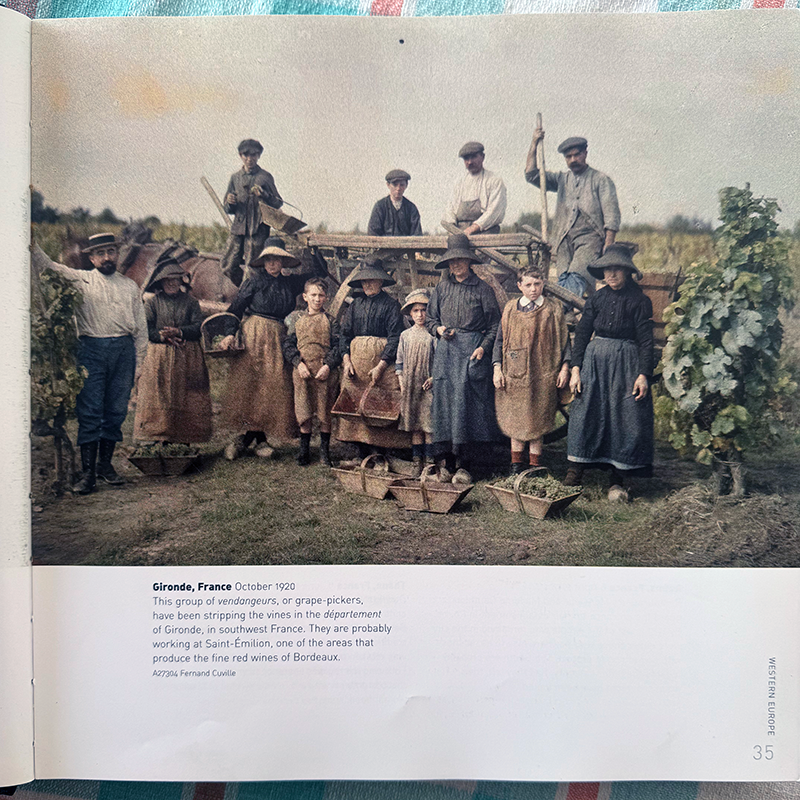

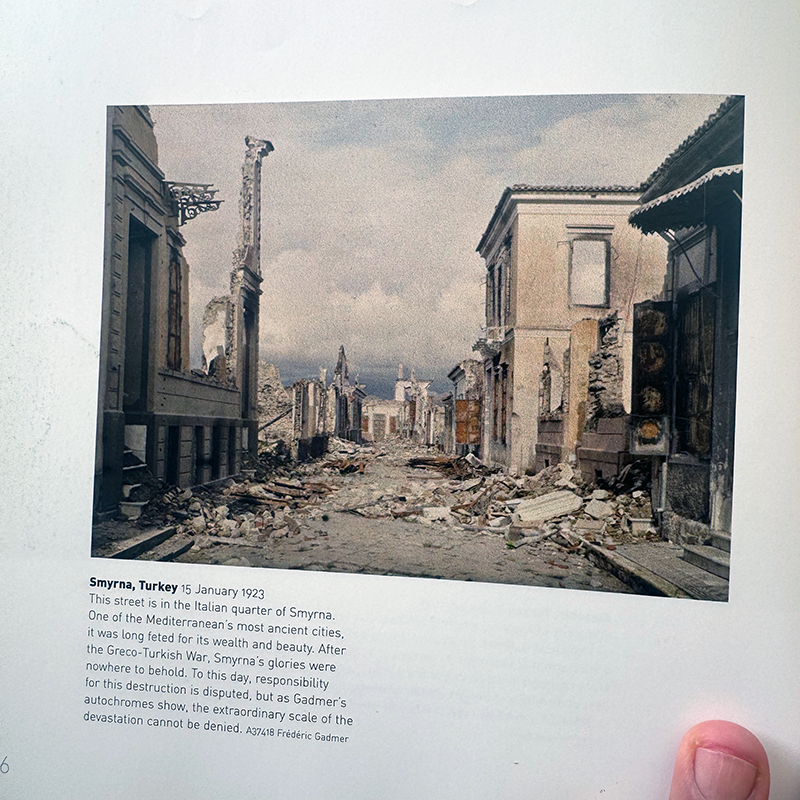

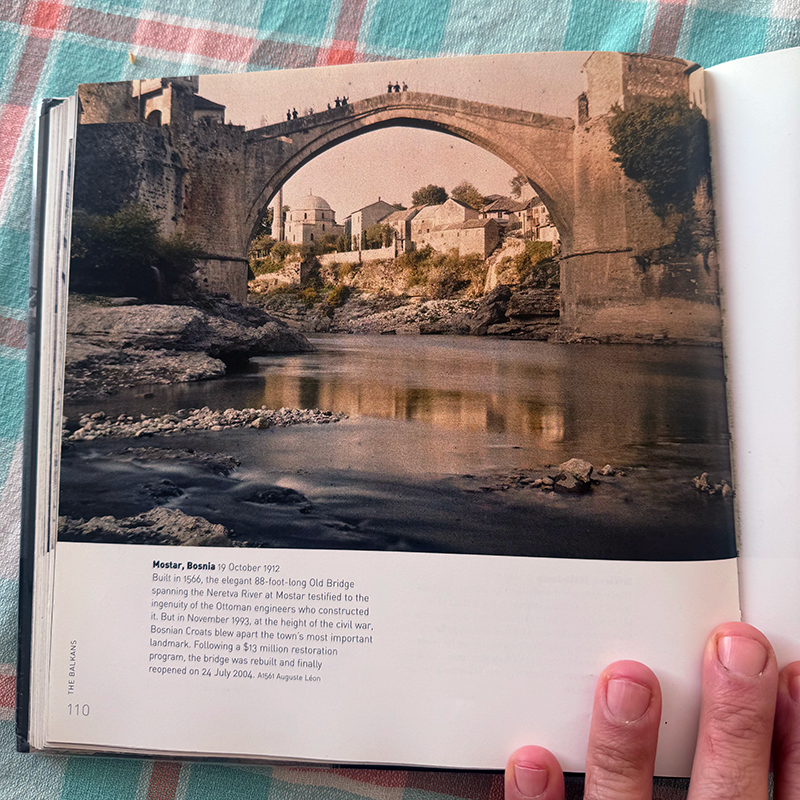

He called the endeavor, which he launched in 1912, Les archives de la planète. And they aspired to be an archive of the vanishing world, using a latent nostalgia as the driving force of the collection, for many pictures were taken with the idea that the things they portrayed would soon vanish.

When he announced the project in November 1911, Kahn knew how ambitious it all sounded, but it needed to be done quickly, he warned, so that his generation would:

“fix once and for all, the look, practices, and modes of human activity whose fatal disappearance is just a question of time.”

Idealized color testimony of the world of yesterday

To capture the aura of a moment in time not yet dominated by convenience and instant communication, Albert Kahn used the latest technology available at the moment, the recently invented autochrome color process from early film cameras. He enlisted many of the best photographers available in France at the time to create a team that traveled to more than fifty countries, compiling a phenomenal collection of human culture at a single point in time, from the first photographs taken in 1909 until the last ones in 1931.

Kahn died on November 14, 1940, so he never saw the imminent occupation of France by Nazi Germany. The Second World War was about to accelerate the wipeout process of what Austrian writer Stefan Zweig referred to as the world of yesterday.

The rise of the Nazi rhetoric to power was the last straw of a tension at the core of Europe that had shaped his own biography: born in Marmoutier, Bas-Rhin, France, on 1860, he was only ten years old when his mother died, a period he associated during the rest of his life with the trauma of the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War, which prompted the family to move to Saint-Mihiel in north-eastern France in 1872. In 1879, he was already a bank clerk in Paris, but his appreciation for humanism only grew, thanks in part to his tutor, philosopher (and later friend) Henri Bergson.

He proved it later in life. The philanthropist died knowing that his team had amassed more than 100 hours of film and over 72,000 autochromes, the precious precursor to color photography, a colossal effort at the time.

There’s perhaps only one literary attempt, though focused solely on one country, that holds a comparison in scope and depth, even if it remains incomplete because it was the work of a single writer: Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie humaine and his depiction of mid-nineteenth-century French society. And, unlike the accessible and instantaneous visual language of photography, Balzac’s work requires the discipline of reading.

How are we planning to document the world?

One century later, as we confront ever-faster shifts in culture (and our ability to focus our attention), human settlement, and the environment, the Archives of the Planet are a vivid time capsule available for anyone to see and be awed, making us ask ourselves how we are planning to document the world we are leaving behind in our lifetimes.

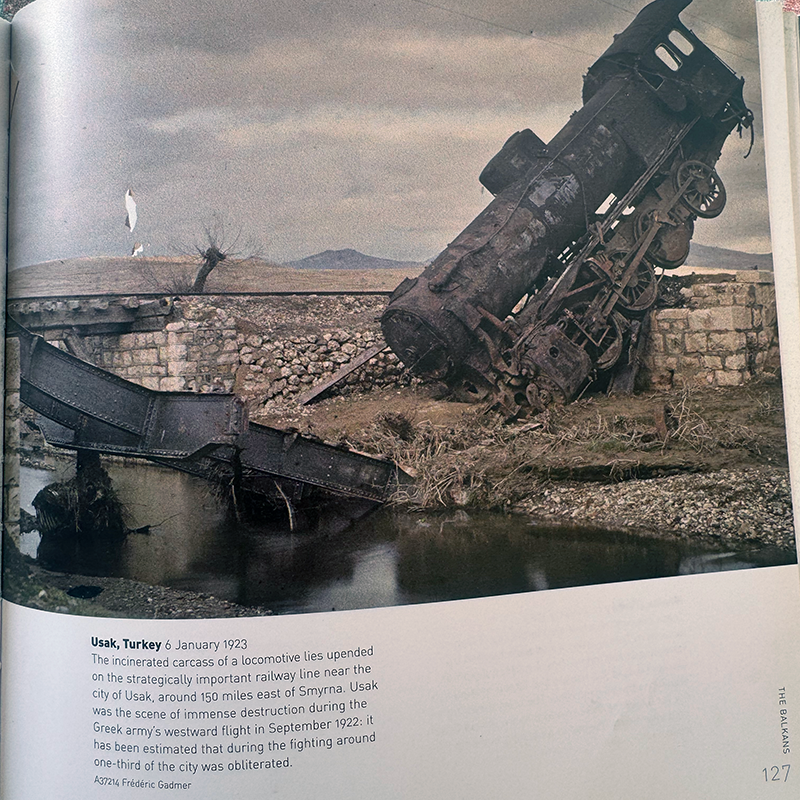

Like one of his friends, the philosopher Henri Bergson, as well as many other influential philosophers of their time (British philosopher Bertrand Russell, or even Albert Einstein, both pacifists), Albert Kahn was a pacifist and believed that knowledge could promote understanding between people. However, as he saw in his lifetime time and again, his universalist naïveté was contradicted across the world, and the archives also include the all-familiar traces of war, dispossession, or ethnic cleansing, as colonial realities like the Ottoman Empire imploded.

Additionally, the photographers working for Les archives de la planète carried a particular baggage: they were French men on assignment, viewing the world from their Eurocentric perspective, and they intended to frame their subjects according to their pseudo-anthropological mission of collecting, classifying, and preserving cultures in time. And, by framing people’s experience as timeless, authentic, and static (the contradiction of capturing life in a “still”), they were using the archive as an unplanned method of control: it froze in time non-Western cultures, preserving their idiosyncrasies but also freezing them in an eternal present while the Western world moved forward.

Scholars debate the origins of the Western perspective, and Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon serves as evidence of this. Whether Herodotus’ descriptions were already “otherizing” remote cultures is a matter for others to resolve, but as modernity advanced, the relationship between Europeans and outsiders was resolved through colonialism and a perception of intrinsic cultural superiority.

How to travel aware of the moment: Nicolas Bouvier’s take

Albert Kahn’s project, for example, can’t be completely detached from the Western process of idealization of exotic cultures and peoples, a phenomenon analyzed by Edward Said in the concept of orientalism: when hegemonic knowledge is produced from one perspective, the produces assert a vision and one idea of cultural superiority, and we see orientalism at play in many places today, especially in social media.

A century later, Google Street View, social media, satellite imaging, and millions of smartphone pictures taken every instant expand Albert Kahn’s dream of creating a total planetary archive, and they are also flawed, reproducing the same blind spot: the illusion of neutrality in perception—and a familiar asymmetry: the world was to be archived by the West, for the West. And so, the images of “others”—the veiled woman in Algiers, the barefoot child in Hanoi, the shepherd in Anatolia—condemned those places to their picturesque version.

But cultural points of view are never neutral, even when many of us perceive it as so because we were born into it: fish don’t know they are in water, or in any case don’t ask themselves about it, nor see it as an oddity. And so, Kahn’s project overlaps temporarily with French colonization in North Africa and Indochina.

In a way, Albert Kahn’s archives are a valuable piece of the world of yesterday, a place that is no longer coming back, having lost nuances, traditions, particularities, and vernacular ways. But we shouldn’t forget the world has always been a place deeply-rooted cultural interchange, creating in-betweens that gave rise to syncretic cultures, first all over Eurasia and Africa through ancient commerce routes like the Silk Road or Africa’s Salt Route from Sub-Saharan Africa and through the desert into the Mediterranean and Europe; and then accelerated in the so-called Era of Discovery and the Columbian Exchange, which made us who we are today.

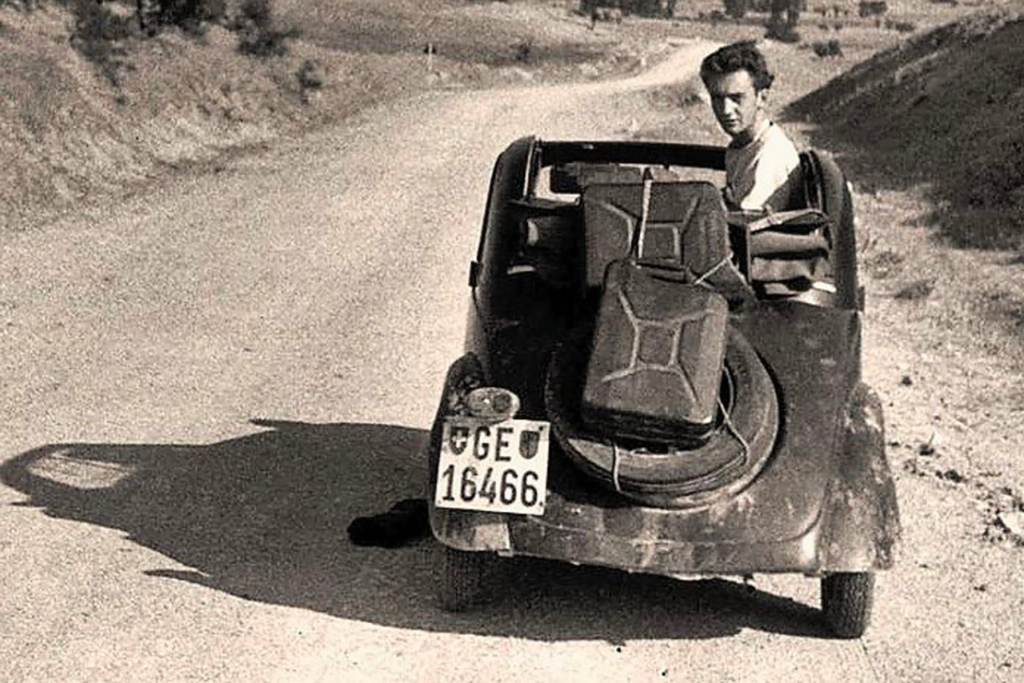

Years ago, when we lived in Fontainebleau, a quaint little enclave with a monarchist tradition attached to a hunting royal palace and the first official Natural Park in the world, the Forêt de Fontainebleau, a couple friend of ours recommended me a Swiss travel writer, Nicolas Bouvier, in particular his book The Way of the World, a delice of a story written in first person and with conceptual drawings by Thierry Vernet, his travel mate during a part of the voyage. In the early fifties, Bouvier and his friend left the neutral, kind Alpine nation in their small FIAT Topolino car with the Quixotic intention to drive all the way to the Khyber Pass into the Indian subcontinent with it.

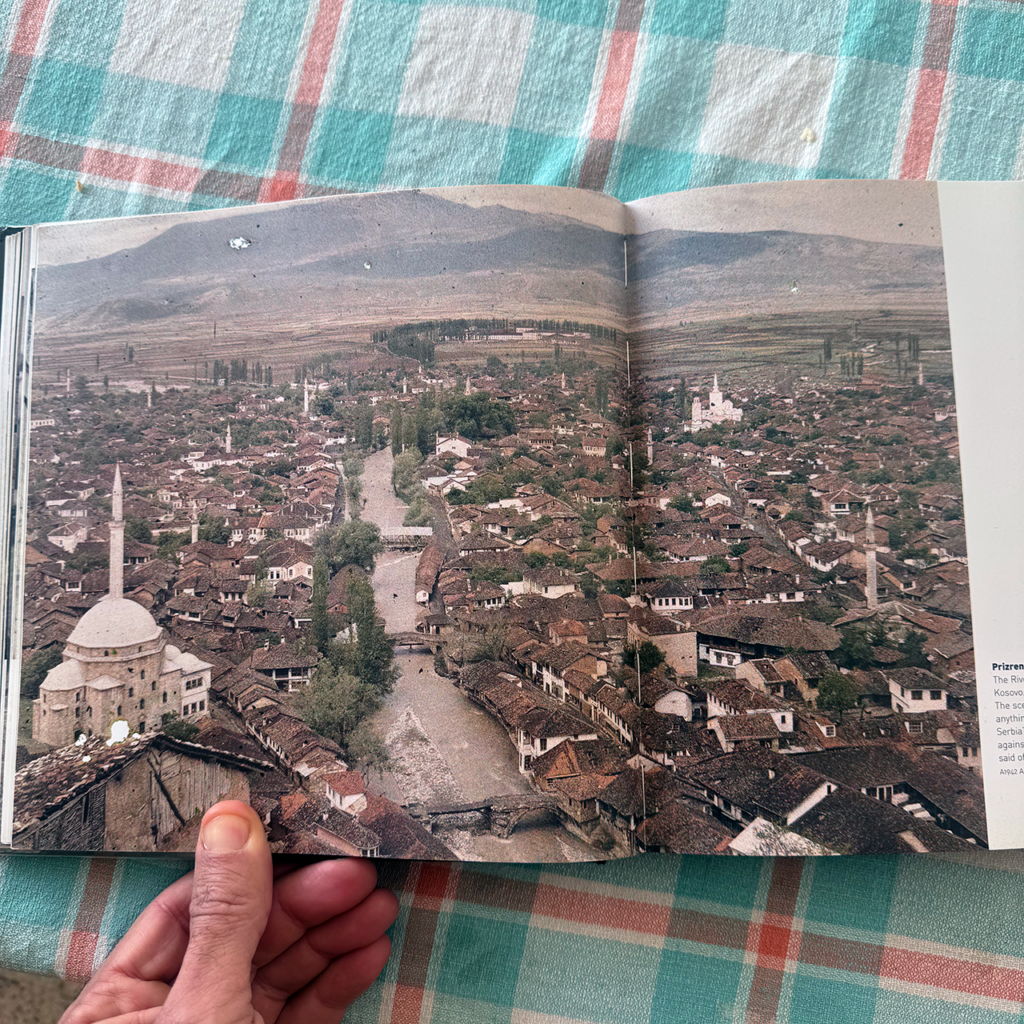

To do so, Bouvier crossed the Balkans, Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. His telling is a testament to a witty, respectful perception that allows us to see through the rich cultural layers of Ottoman rule in the Balkans, as well as the old shadows of past migrations, cultural idiosyncrasies, the Silk Road, and modern colonization.

Real Indiana Jones of the American West: Edward S. Curtis

And so, Kahn’s project escapes the trap of orientalism as the images taken outside Europe are always respectful and highlight the pride of the subjects depicted instead of staging their behavior, much like Edward S. Curtis was capable of doing when he photographed Native Americans in their context and not “assimilated” by the hegemonic world that had fallen onto them.

Both works are a present to all of us, though they also remind us that even utopian pacifism and universalism are constructions and depend on a hegemonic point of view peeking into the world: in the past, it was a colonial hegemony, whereas today it’s cultural and economic.

Hence it’s not a surprise that many countries try to develop their own cultural hegemony and point of view, given the advantages that soft power carries: in his late years, Alexander Solzhenitsyn tried to explain to the world how Russia didn’t see itself as a byproduct of the peripheral West but as an autonomous culture with its own point of view, one that had Eurasia as a foundational reality and not as a mere expression of colonization; but the most notable example of a point of view to export to the world along with products and services is that of China, which centuries after Zeng He sailed the Indian Ocean and decided to come back instead of conquer, is trying to amend the consequences of that strategic decision, which favored the West.

Albert Kahn’s photographs survive as luminous contradictions — mechanical reproductions that still emanate presence. They remind us that every act of looking is also an act of vanishing: what we see changes in the moment we capture it.

Benjamin feared the death of aura in the age of machines. Yet a century later, as we scroll through billions of frictionless images, it’s the fragile, imperfect colors of Kahn’s autochromes that feel alive — that shimmer of human attention before everything became reproducible. Perhaps aura isn’t something we’ve lost but something we must learn to cultivate again: not in objects, but in the way we look at the world, and in how we choose to build and preserve it.

When you think you’re making a trip

When, in 1953 — thirteen years after Albert Kahn’s death — the Swiss writer Nicolas Bouvier set off in his small Topolino toward the Khyber Pass from his Alpine hometown, he didn’t know the experience would become a book that would inspire generations to seek the aura of reality through travel: to reflect on landscapes and other peoples, present and past, and in doing so, to know ourselves a little better.

In his “way of the world” (L’usage du monde), Bouvier describes travel not as collection or conquest but as transformation: “You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you.” Bouvier’s prose, stripped of exoticism, finds aura in the everyday —the hum of a bazaar in Tabriz, the dust on a shoe, the shared silence of a roadside meal.

Between Kahn’s monumental archive and Bouvier’s modest journey lies the century’s moral evolution: from archiving the planet to inhabiting it. What Kahn preserved through the lens, Bouvier learned through attention. And if aura has a future, it may reside there: not in the image we capture, but in the patient art of being present in the world.

Perhaps that’s what our teenagers mean, without knowing it, when they talk about someone’s aura: not charisma, but presence —the rare ability to be fully here, before the moment scrolls away.