We don’t just move through the world: we can help compose it with attention (and intention). The same street can be a threat to one person and a home to another. When we connect things, a world forms.

Many of the ills of our times stem from people’s insistence on viewing the world through a lens of fear and ugliness. And, if you look at reality defensively, you end up making the world around you a bit darker, uglier, and less inviting for everyone.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, indeed. Or, perhaps better said, beauty is in the eyes of the beholder IF the beholder is with the right attitude at every moment. One of the key minds of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume, dedicated one of the central points of his 1757 essay Of the Standard of Taste to addressing this problem, especially acute in modernity: that many things in our reality depend on individual perception:

“Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty. One person may even perceive deformity, where another is sensible beauty; and every individual ought to acquiesce in his own sentiment, without pretending to regulate those of others. To seek the real beauty, or real deformity, is as fruitless an enquiry, as to pretend to ascertain the real sweet or real bitter.”

David Hume, Of the Standard of Taste (1757)

Experience as architecture

Now, we could flip this argument around and state that the most luminous figures make reality better by looking into the world with a glass-half-full attitude, no matter the hardships. Beauty is perceived, not inherent to someone or something; from this standpoint, if we take the time to direct some attention to things, we’ll always find signs of goodness, even in dark places and dark times. If we don’t forget this, we can make our days, the days of others, and reality itself a bit better, one perceived moment at a time.

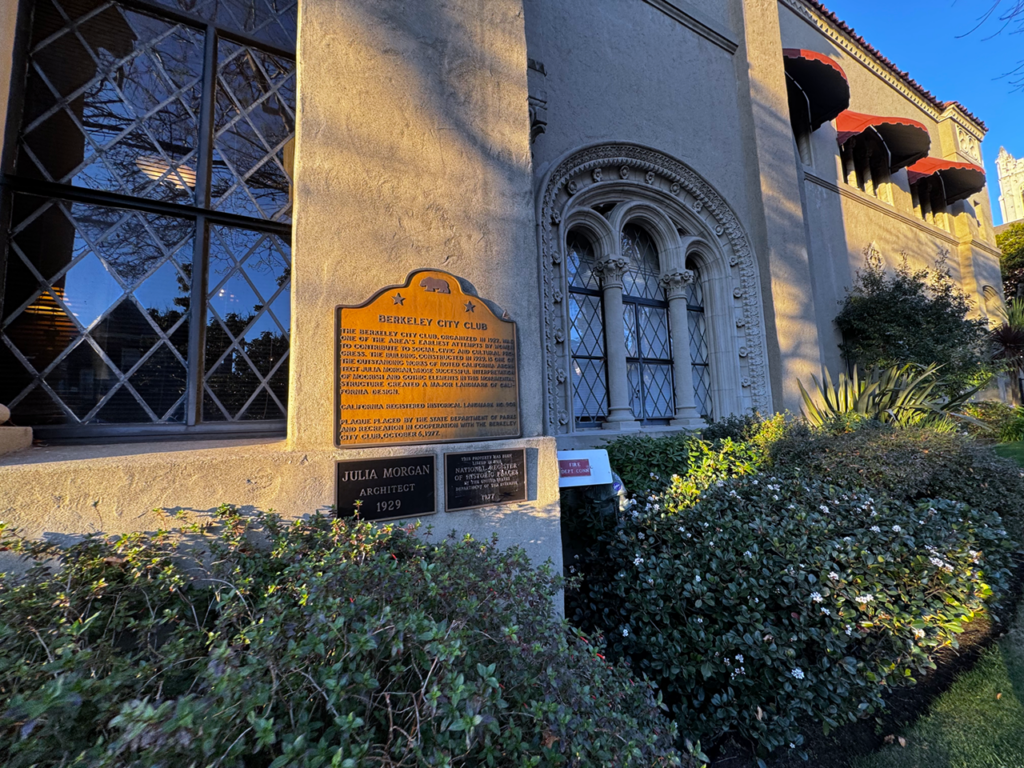

Recently, as we had a wonderful dinner at the Berkeley City Club’s restaurant, marveled at the fantasy world created by reinforced-concrete pioneer architect Julia Morgan in 1929, I had perhaps the right mindset to appreciate the Gothic windows and Moorish arches. I was in California, but I’m also from Spain, and the many churches and buildings I’ve been exposed to all my life were telling my subconscious the tale of relatedness and continuity.

The same way a French person from Normandy or Brittany won’t feel totally foreign walking inside the old buildings and churches built by the likes of Jacques Cartier along the St. Lawrence River at the heart of Quebec, or the British walking along the many spatial references of the Thirteen Colonies, I can’t feel totally foreign in places such as California, if only when trying to learn to pronounce Spanish streets, roads, and last names the way locals do.

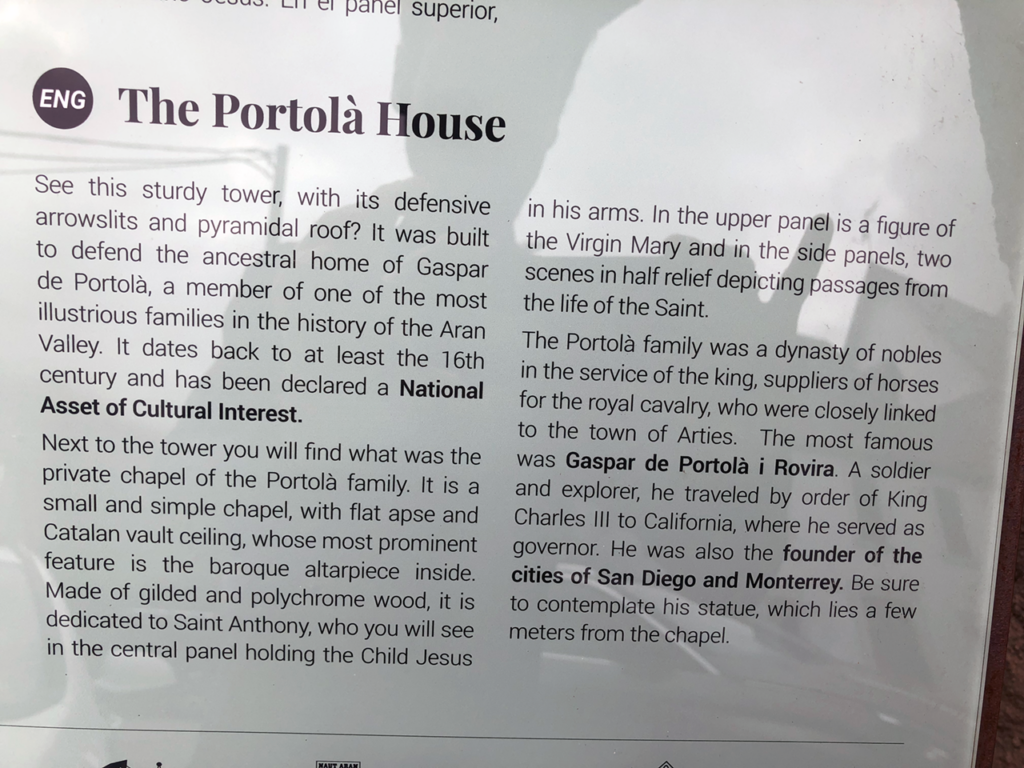

And then there are the Missions, the controversy around the Padres, and the fact that colonist Gaspar de Portolà’s family comes from the wonderful Pyrenean Val d’Aran, a self-contained world on the Spanish side but of Occitan culture, a place our family cherishes. Not very far from the ski resort of Baqueira, in Arties, the national hospitality network Paradores restored the medieval tower that the Portolà family claimed as their clan’s home into a very special place worth visiting.

What places do to us, if we allow awe to happen

To add more texture to the melody of references bringing me back home when I go around in places such as the Bay Area, when I few years back Kirsten and I decided to pay for a genetic test so we could guess our potential medical evolution growing older, I also noticed that the biggest prevalence of my paternal genetic markers (haplotype) is, well, Val d’Aran (also, quite interestingly, it’s a marker connecting me to old Irish kings, go figure).

So having dinner at the Berkeley City Center with our interesting and kind hosts before giving a lecture within their Arts and Culture sessions was interesting enough, but then I happened to find myself walking the recreated old-Spanish world of Julia Morgan, her “little Castle” in the middle of craftman-style-rich Berkeley, and I couldn’t help but “see” many many things.

The way our senses relate to our experience can be otherworldly, and I can relate to both the so-called awe shock of the Stendhal Syndrome, Proust’s madeleine, etc.

Nobody like Proust to describe the will of our involuntary memory to manifest beauty:

No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. … Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? … And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time (1913, first English publication 1922)

From a California building to an old Gothic hospital

If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, the past can be both a burden and a well of wisdom in which we can dwell and get propelled to new frontiers instead of being held back. Talking about Julia Morgan’s wonderful blends, like her perception of Gothic with Moorish, I see much more than an Arts and Crafts-inspired pastiche, and I don’t need to prompt any AI or take any substance to induce this hallucination — I just need my senses, experience, and walking into a place with so many layers as the Berkeley City Club.

When I met Kirsten over twenty years ago, I was living in the walkable Gothic Quarter of Barcelona, and I wouldn’t have thought of the Catalan Gothic corners of our neighborhood, which we walked extensively with our then toddlers, had not one of the hosts sitting by my side about that very neighborhood, which she liked. I explained how our life was there, and how sometimes I’d walk with our then-only daughter to the orange-tree patio of a Gothic landmark at the heart of El Raval on the side of the Ramblas, where there was a calm, monastic ambiance, and also one of the many public libraries in the city, with an extensive section for children.

This memory flashback might have come and manifested itself in my mind as our oldest daughter, now in college, turns nineteen years old today, and as she openly expresses to me during our most recent conversations that she wishes us to speak to each other in Catalan instead of English (or French, or Spanish), for that’s the language of a world we shared that now is mainly dormant but lives vividly in her early childhood memories. Reality would be much poorer if we just were to focus on the bare perception of things presented before us at every moment, and embracing experience, good and bad, is a necessary part of the human experience, and what makes our species stand apart.

Back in the days when she was just a toddler (though a multilingual, very articulate one), the elegant and sober Gothic edifice hosting the public library open to all also hosted on one of its cathedral-like wings the enchanting main reading room of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, old custodian of Catalan culture, keeping valuable Medieval manuscripts and artifacts, and also a book collection worth preserving.

A plaque in the cloister

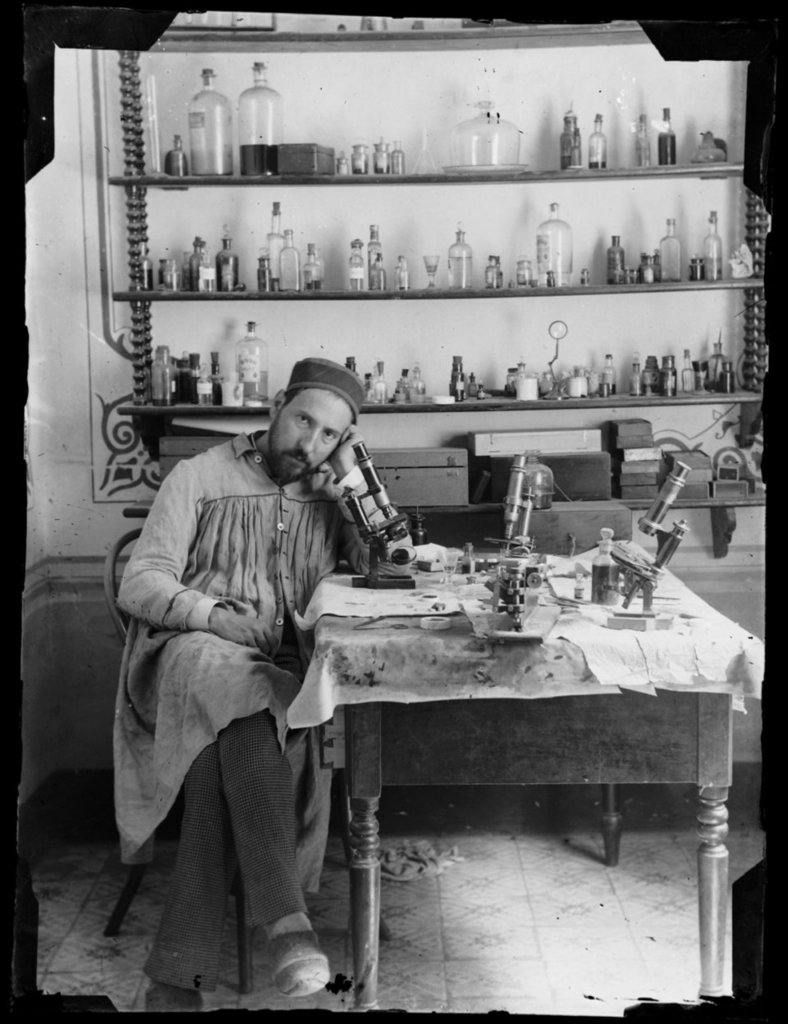

There, to the side of one of the Institut’s sumptuous entrances, there was a commemorative plaque dedicated to one of the many doctorate students of the associated University of Barcelona, pioneer neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who went on to earn the 1906 Nobel of Medicine along with Camillo Golgi, one year after a little known patent clerk called Albert Einstein published four groundbreaking papers that changed the way science saw the world.

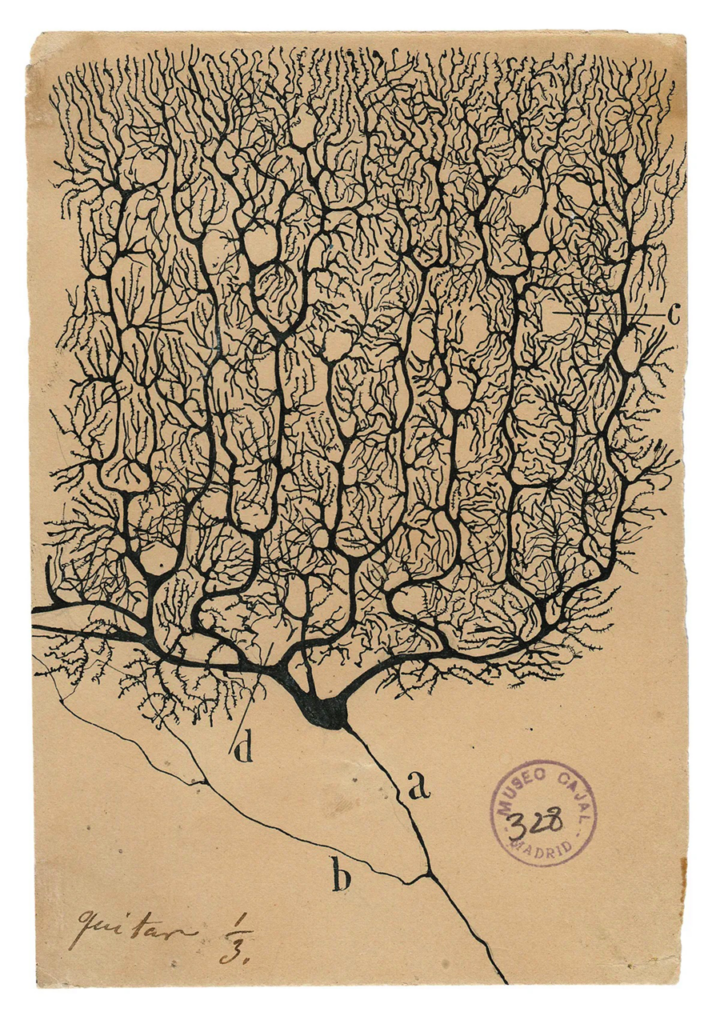

Ramón y Cajal’s work in neuroscience was equally paradigm-shifting: he not only described the nervous system, using microscopic staining to show that it is made of individual, interconnected cells (neurons), but also drew his findings with the sensitivity and skill of an artist. A native of the adjacent inland Spanish region of Aragón, his drawings of neurons and synapses would have interested, and perhaps caused some excitement, to Goya, another universal Aragonese.

Many years passed, and helping Kirsten with our video production brought me to all sorts of obscure, interesting topics. When we visited a mushroom farm in San Francisco, we ended up talking about mycorrhiza, and learning about these forest networks—some sort of “nervous system” in the soil—, I had the strangest feeling of déjà vu. Branching filaments and junctions, the delicate threads connecting nodes that served as exchange points.

It all looked like Cajal’s drawings of neurons. Life hadn’t invented such a design in the skulls of vertebrates, but tested it everywhere: in soil, in roots, and in many infrastructures with which living things cooperate and compete. Taking one of Cajal’s drawings as a model, the cloister at the Old Hospital worked as a node in a quiet network of invisible architecture built on experiences.

I may have looked at that plaque so many times as our two daughters played outside the library, along the old building complex’s main cloister, amid orange trees and students from Escola Massana (another hosted institution) having breakfast or taking a break. I might have been bored enough to notice that it existed at all.

Corners of Old Barcelona

The old stone building complex in the core of Barcelona’s Old City that I’m referring to is the Antic Hospital de la Santa Creu (Old Hospital of the Holy Cross), one of the main surviving ensembles of Catalan civic Gothic. A complex amid cloisters and courtyards, it did make me feel, at times, as if I were performing time travel.

It might also explain why I read so many historic novels at the time and even borrowed from its library the Costumari Català, a monumental compendium of Catalan folklore and ethnography, so bulky and heavy that I remember our oldest daughter marveling at the sheer size of the “books with drawings” that I had to carry under her lightweight-but-sturdy umbrella fold stroller (the complete Encyclopedic work of Joan Amades consists of 5 thick volumes covering the seasons in 5,000 pages, weighing almost 1 kilogram each, or 5 kilos—over 10 pounds—total).

The Old Hospital was indeed an oasis of calm and cultural references, digging deep into the local culture, but it wasn’t isolated from the idiosyncrasies of a multicultural neighborhood that had always hosted the least reputable parts of a harbor city, from absinthe bars (one survives, called Marseille) to places where locals and foreigners search for illicit activities, including drugs and prostitution. Right in front of the Hospital’s southern entrance, a narrow and insalubrious street ran parallel to the Ramblas and the more modern Rambla del Raval, hosting immigrant-owned small stores and bars with makeshift signs that contrasted with the modern-architecture intervention of the Film Theatre of Catalonia, a concrete box with a paved surrounding. If you were a local, you knew that the area around Carrer Robadors was a shady place with a name that couldn’t bring many good things (Carrer d’en Robador means “Robbers Street” in medieval Catalan).

That said, the whole area was filled with beauty, and many writers and artists depicted it over the years. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, a Catalan writer of Galician origin, was born nearby and liked to eat at the restaurant Casa Leopoldo, which survived amid petty crime and ill-reputed dens. During our stay in Barcelona, I always thought the area deserved a chance, and that its opportunity would come only if locals recognized the beauty amid the dysfunctions.

Like beauty itself, social and urban reform can happen only if we perceive the potential and acknowledge that things can change for the better. Vázquez Montalbán’s most famous character, detective Pepe Carvalho, is a cynical post-Franco Barcelonian who navigates the city’s raw edges with ease, self-conscious about the many tough realities of the “Barrio Chino” (the informal name for El Raval) as it changes. An alter-ego of sorts, Carvalho loves eating well and walking the narrow streets of a raucous and unrepentant area of the city. I never quite connected with Carvalho, but I understood the way he saw that part of Barcelona.

Street of thieves to some, street of life to others

Years passed, and our oldest daughter had two siblings; first, we moved from our apartment in the nearby Gothic Quarter to another part of town, and then to France. Yet the area surrounding Barcelona’s Old Hospital de la Santa Creu stayed with me, perhaps because we used the city’s library branch and the kids’ library inside the ensemble’s old courtyard.

When in Fontainebleau, I asked a neighbor whether he recommended any reading; he politely told me that he read a lot, mind you, but he didn’t read “serious literature.” When I asked him what he meant, he basically said he devoured “polars,” the French term to designate the massive subgenre of “littérature policière,” or crime and detective fiction. I added that I was also interested in those reads. So, he said, “I actually read one recently that I recommend, based in your city.”

That’s how I came across Mathias Enard’s 2012 novel Street of Thieves (the original title is Rue des Voleurs; I read it in the French edition borrowed from the local library). I didn’t initially associate its title with anything, but soon it became clear that the Street of Thieves mentioned in the title was… Carrer Robador, the same ill-reputed, narrow street running parallel to the Ramblas. It struck me as a coming-of-age novel, and I really enjoyed the fact that the protagonist, who tries to prosper in a rough world, is a Moroccan lad from Tangier who has to navigate the realities of the modern world and live as an undocumented immigrant in Europe.

I soon sensed that Enard had a deep knowledge of the Arab World, and the novel’s background talked about the challenges of finding a home when homeless, the dangers of religious extremism when one feels excluded, the shadow existence of immigrants, and the events of the Arab Spring. But in essence, Lakhdar’s journey from Morocco to Barcelona wasn’t that different from the abundant French literature depicting the drive and hopes of the “arribiste,” the social climber who tries to become somebody in the big city (almost always Paris). As I read the novel, there it was, the corner of Barcelona that I had seen with other eyes and perceived experience.

A French writer, avid reader of “polars”

The reader soon understands that, despite the difficulties, Lakhdar sees beauty in the world, including in the Street of Thieves. I imagined him walking the courtyard of the Old Hospital, fighting alienation as well as he could, thinking that I would probably have a thing or two to learn from him. When reading Enard’s book, I realized he knew the city well, so I looked him up and realized he’d moved there. I also read that he had studied Arabic and Persian, had completed his military service in Syria, and had taught French at a cultural center.

Street of Thieves is not a feel-good book, nor an apology for illegal immigration (or the opposite: today’s much-supported Great Replacement theory); it’s just the story of a young man kicked out of his house who wants a better life and sees the bright side of existence despite the odds and the ugliness stacked against him.

The perspective of his book seemed to make the city better, giving outsiders a voice that isn’t paternalistic, condescending, or worse. I found it refreshing, especially in a moment when local nationalism was trying to put people in clear-cut identitarian boxes. Perhaps it wasn’t an accident that the writer wasn’t a Barcelonian by birth but by choice, and a recent one, for that matter.

By marrying outside my culture and starting a family that would need to navigate the nuances of identity and place, I realized how lucky I was, for I seemed to be consistently on the easy side of a world that was becoming more identitarian, less tolerant.

Almost two decades after my walks to the public library at the heart of the Old Hospital de la Santa Creu with my baby daughter, I find myself thinking about all this. And proud of my daughter. Proud of her willingness to connect to our complex reality in a world that is trying to erase it, and eager to hear what she has to say about the world from now on.